Loneliness

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Spy

John Le Carré's spies lead lives that highlight the dangers of loneliness.

Posted February 25, 2019

Spoiler alert: I tell the ending of The Spy Who Came In From the Cold.

Loneliness hurts, as John Cacioppo and William Patrick demonstrate in their book on the topic. When people feel lonely, the same part of the brain activates as for physical pain. There’s a reason for this. Loneliness evolved to get humans to connect with one another because, as we still say today, there’s safety in numbers. Conversely, social connection feels pleasurable. Not only does it make us feel good, but it also helps us to down-regulate negative emotions. And so we often turn to others in times of stress.

Our minds, brains, and bodies respond to loneliness as to other dangerous situations. This means that for the chronically lonely, stress and arousal systems activate for long periods of time, even continuously. Activation of this kind can lead to many health problems, including high blood pressure, inflammation, and compromised immune systems. Isolation is right up there with high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, and lack of exercise as a risk factor for illness and. premature death.

The situation isn’t much better for our mind-brains than it is for our bodies. Stress symptoms inhibit executive function and emotional regulation. This means that lonely people might be less able to think clearly or to regulate their emotions, especially negative ones. Such impairments pertain especially to social cognition; loneliness skews social perception negatively. Feelings of unhappiness together with a compromised ability to regulate negative emotions means that lonely people tend to distrust and reject others. Their ability to take others’ perspectives is also impaired and skewed towards the negative. People who are chronically lonely tend to blame others and lash out all too easily. They don’t find comfort in the company of other people, and the greater the loneliness, the less likely they are to seek emotional support.

These traits would be problematic for most of us—most lonely people don’t want to be lonely even if they feel helpless in ameliorating their situations. But if you’re a spy, such qualities might be an asset: All of the negative traits mentioned might well be included in a job description for recruiting intelligence agents. If you’re a spy, feeling negative and distrustful as a way of life will probably protect you more often than not. It’s good not to get too close to people. Or to empathize with them, which can come from taking another’s perspective, because that might interfere with the ruthlessness needed to do your job. Better to be distrustful, commitment phobic, footloose and fancy free—a loner.

And so most of John Le Carré’s secret agents are loners. They fraternize with one another at their clubs, but such connections rarely achieve true closeness. Early on in Le Carré’s series of Smiley novels, we discover that one of the most trusted (well, insofar as you can trust) and popular directors of the agency is a mole, a spy for the Russians who has been compromising their operations for years. That’s a lesson in the benefits of staying lonely; the popularity of the mole might well have postponed his detection because even those who choose loneliness as a professional necessity are vulnerable to the appeal of bonhomie. Le Carré’s spies tend to be divorced or never married, and if they have children, they’re usually estranged from them. Family belongs to a remote past, a past has to be left behind for the agent to achieve the psychological distance necessary for the job.

Le Carré is deemed a popular writer, a master of the spy novel. This judgment is far too narrow and naïve for this superlative author. Sure, Le Carré tells a great story. But in addition to his stunning use of language and his cleverness at constructing byzantine and surprising plots, he portrays the psychology of spying, and, by extension, of all the ways in which we turn away from the better parts of human nature.

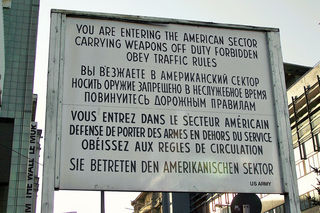

In The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, the spy is Alec Leamas—a surly loner. Another important main character is the Berlin Wall, which has divided a country that ought not to be divided, divided families and friends, and stands as an ugly reminder of war, enmity, and hostility. It is an enduring tool and symbol of the Cold War, so named because neither Russia nor the U .S. officially declared war; hostility was sustained without the “heat” of battle. But coldness in this novel also alludes to the conditions of life for a spy, his or her banishment from the warmth of human friendship, trust, love.

Leamas is given a mission to take down a Russian spy that involves pretending to be a defector. To establish his seedy credentials and attract the opposition, he first begins to drink heavily; is supposedly fired from the Circus, the name given to MI6 by its agents; and spends some time in jail for assault, so continuing his performance of a downward spiral. When he gets out of jail, he begins working at a library where he has an affair with a worker named Liz. She cares tenderly for him and is obviously in love.

The Circus’s plot succeeds. Leamas is recruited by enemy agents, ostensibly defects, and is taken to East Germany. He thinks his task is to discredit a man named Mundt, a major official in the Russian secret service. But what Alex doesn’t know is that he is being played by the Circus, that Mundt is actually a spy for the British (a mole), and that Alec will be set up to discredit Mundt’s enemies (the men who recruited him) rather than to take down Mundt. As he later realizes, he had not found his job at the library randomly after visiting an employment agency, but he was set up by the Circus to find employment there in the hopes that he would become involved with Liz, who is a communist sympathizer. Mundt’s agents trick Liz into coming to East Germany, and both she and Leamas unwittingly help him to defeat his enemies. Mundt is a moral reprobate and the man opposing him is a far better person, but Mundt must be saved from exposure to further the aims of the Circus.

Liz is forced to testify at Mundt’s hearing. Leamas has no idea that she has fallen into the hands of Mundt’s agents and is shocked and appalled to see her when she enters the courtroom. She wants to say whatever will help Leamas, but of course, she doesn’t know the situation, which Leamas suddenly grasps. Her testimony reveals that Leamas is still working for the Circus, and Mundt’s enemies, (who recruited Leamas) are discredited.

At one point during the hearing, Karden, one of the interrogators snidely says, “Leamas had done the one thing British intelligence had never expected him to do: he had taken a girl and wept on her shoulder.” Karden is right insofar as this cold-blooded spy who has let no one into his life cares deeply about Liz. Before he was taken to East Germany, he dreamed of returning to her after this assignment. However, Karden is wrong in thinking British Intelligence didn’t predict this. They saw that Leamas was near his breaking point, burning out as a spy, and they intervened by exploiting his weaknesses. There is no private life for a spy, and taking advantage of Leamas’s need for safety and authenticity was deemed fair game in achieving the ends of espionage.

Mundt allows Leamas and Liz to leave. To escape they must climb over the Berlin Wall. But Mundt is not trustworthy, and he sends his assassins after them, as Leamas suspects he will. They have a chance of making it to safety by climbing over the Wall before they are detected by searchlights, but as they are climbing, Liz is shot and killed. Alec is on the brink of the wall. Smiley and other agents on the American side are shouting at him to jump, to return to safety. But Leamas jumps down to the Russian side where Liz lies lifeless. He is killed by a firing squad.

The ironies of the title abound here. Earlier in the novel, Control, head of the Circus, had told Leamas that after this last assignment, he could retire and “come in from the cold.” Control uses the metaphor of coldness to mean a lack of human warmth and connection, the loneliness a spy must live without respite if he is to be successful at what he does—if he is to survive. But by falling in love with Liz, Leamas has already come in from the cold. In a world without her, he would still be in the cold, even if he joined his colleagues on the American side of the wall. As Cacioppo and Patrick point out, loneliness consists not in the number of people one knows and sees (such as colleagues) but in the quality of connections. Leamas’s colleagues are people he has lived among most of his adult life, but there is no intimacy or true emotional connection there. They want him to live, and they care about him as much as they can care for anyone, but their role in the Cold War takes precedence over all relationships, as their willingness to use Leamas as a pawn has shown. And so, Leamas comes in from the cold not by retiring but by joining his lover in death. Death, which makes bodies cold, is the warmer alternative to a life without love, a lesson Leamas has learned late in the day.

The novel begins and ends at the Berlin Wall, both a real, physical entity that divides people from one another, and a symbol of alienation. At the macro level of politics, the Wall makes nations alien to one another (alien-nation), that belong together. It is also a metaphor for loneliness at a personal level, the personal barriers the spy must build in order to do his job. Robert Frost wrote that “good fences make good neighbors,” a metaphor which wisely points out the necessity of boundaries. But good fences also make good prisons, and solitary confinement is the cruelest of all punishments inflicted on their residents.

The Circus believes that they are justified in sacrificing individuals for the greater good, and this includes asking their agents to live in solitary confinement. But as The Spy Who Came In From the Cold demonstrates, there might not be a greater good. What does it say about them that they allow a basically good man like Fiedler, Mundt’s enemy, to be killed while allowing Mundt, a Nazi war criminal, to continue in power and ease because he passes information along to them?

Even so, Leamas defends them to Liz as they approach the Wall:

What do you think spies are; priests, saints, and martyrs? They’re a squalid procession of vain fools, traitors too, yes; pansies, sadists, and drunkards, people who play cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten lives. Do you think they sit like monks in London, balancing the rights and wrongs? I’d have killed Mundt if I could, I hate his guts, but not now. It so happens that they need him. They need him so that the great moronic mass you admire can sleep soundly in their beds at night. for the safety of ordinary, crummy people like you and me.

Leamas does not express Le Carré’s opinion, the judgment that emerges from the book as a whole—what literary critics call “the implied author.” In his latest book A Legacy of Spies, Le Carré revisits the events and characters that figure in this earlier novel. It’s a different time. The Berlin Wall has been down for decades, and its fall was the event that more or less announced the end of the Cold War. Le Carré’s main character this time is Peter Guillam, an agent seen throughout the Smiley novels. Legacy is a great work, a brilliant tour de force. It is also this author’s clearest statement that what really matters is human connection.

References

Cacioppo, John T. & Patrick, William (2008). Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need For Social Connection. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Jones, Wendy (2017). Jane on the Brain: Exploring the Science of Social Intelligence with Jane Austen. New York: Pegasus. [Chapter 3 describes the workings of stress systems in the mind/brain; chapter 8 describes the connections between attachment and the ability to regulate emotions.]

Le Carré, John (2017). A Legacy of Spies. New York: Penguin Group

Le Carré, John (1963). The Spy Who Came In From the Cold. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc.