Sex

Dissociation as Self-Defense in Childhood Sexual Abuse

When your mind leaves your body to protect yourself.

Posted December 30, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- According to the CDC, 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys experience childhood sexual abuse.

- Victims often experience dissociation and out-of-body experiences during and after the abuse.

- The temporoparietal cortex is a major site for dissociation and out-of-body experiences.

- Long-term consequences of dissociation include disgust of one's own body and body dysmorphia.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys are subject to sexual abuse during their childhood, although this number is thought to be underestimated due to a lack of reporting.

Childhood sexual abuse varies greatly in form and degree. In 91 percent of cases, it is a family member or a trusted friend of the family that commits the abuse. Thus, not only does the child experience a huge overstep in physical boundaries, there is also an enormous break in trust, which can have long-lasting consequences for how the child builds and maintains relationships throughout their lives.

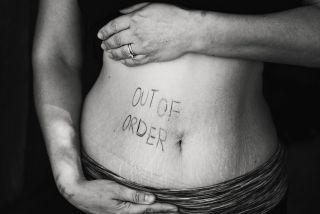

A common experience among survivors of childhood sexual abuse is out-of-body experiences and dissociation, both during and after the abuse takes place. One person whom I interviewed for this article described their experience like this: "I usually see myself and my actions from above or beside me, or just feel frozen and not at all present” (R.J., age 16, New York). They are also more likely to feel as if their body does not belong to them. The perpetrator, or anyone, can do what they want with their body, and they emotionally disconnect themselves from their bodies, such that “a lot of the time I just don’t care what happens to my body.”

What causes out-of-body experiences and dissociations?

Researchers still debate this, but one brain region has received considerable attention: the temporoparietal junction (TPJ)1,2. The TPJ resides right where the temporal lobe meets the parietal and occipital lobes, which makes the location apt for multisensory integration. In other words, the TPJ integrates lots of sensory information that is important for forming and maintaining a sense of where you are in space (also called proprioception) and how you perceive what your body looks like. Electrical stimulation of the TPJ in people undergoing brain surgery leads to altered body perceptions (your arm or legs start changing size) and out-of-body experiences. But it’s not just about the TPJ. No brain region works alone, and the TPJ appears to work together with the insula and the cingulate cortex to trigger dissociations and out-of-body experiences3.

The insula is of particular interest because of its role in interoception, that is, the ability to sense our body. Women with histories of severe childhood trauma have reduced body awareness, and have a more difficult time attending to and identifying internal sensations4. For example, they may have a difficult time telling if they are feeling hungry, if they are cold, or even if they are experiencing physical pain. “When I am at the hospital, I am unable to 'rate' my pain. This inability is one of the reasons my self-harm became so bad. I harm my body way past its limits” (RJ, age 16, New York). In cases like these, a patient's mind has literally separated from their body.

Case studies demonstrate that people with histories of sexual abuse are much more sensitive to the Rubber Hand Illusion: they find the hand too real, too quickly, triggering dissociation and depersonalization5. This likely happens because survivors of sexual abuse have a more difficult time integrating sensory information from multiple sources (for example vision, touch), triggering dissociation as a self-defense mechanism. This stands in contrast to people with other mental illnesses, such as eating disorders (with no history of childhood sexual abuse) that are more likely to adopt the Rubber Hand as their own without dissociating. While people with eating disorders also have alterations in their ability to integrate multiple sources of sensory information, they do not experience dissociation during this experiment. This emphasizes how childhood sexual abuse can uniquely shape a person’s brain into disconnecting from their body.

What are the consequences of dissociation and out-of-body experiences?

While dissociating and out-of-body experiences are fascinating phenomena, they can have severe consequences for how people relate to their bodies. A study found that women with severe childhood trauma report higher degrees of negative body images4, including disgust and shame about themselves.

This feeling was echoed in my interviews: “I felt so disgusted about my body and sexual parts. So much so that I physically could not eat” (K.P., age 34, Florida). Her self-disgust, a sensation arising from the insula, triggered a long-lasting eating disorder.

Another patient described how “my body doesn’t fit me” (R.J., age 16, New York). The childhood sexual abuse has not only broken a trust barrier, but it also changed the way their brains perceived themselves. Instead of understanding themselves as a complete person, they dissociated their mind and body. Their mind became theirs, while their body belonged to the perpetrator(s).

Shifting this perspective, and re-integrating your mind and body takes many years of work and lots of support. But it is not impossible. “I no longer feel shame about what happened. I have told everyone that cares about me, and they love me anyways” (K.P., age 34, Florida). This was a moving sentence from a survivor of childhood sexual abuse and it goes to show how internalized the feelings of shame and disgust can become. Instead of blaming the perpetrator, children often blame themselves. They think of themselves as having disgusting and shameful bodies, with consequences for how they develop new relationships, process emotions, and perceive themselves. It is not surprising, therefore, that people with childhood sexual abuse are more likely to develop eating disorders, body dysmorphia, and other forms of body-related mental illnesses4.

References

1 Bünning S, Blanke O. The out-of body experience: precipitating factors and neural correlates. Prog Brain Res. 2005;150:331-50. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50024-4. PMID: 16186034.

2 Blanke O, Ortigue S, Landis T, Seeck M. Stimulating illusory own-body perceptions. Nature. 2002 Sep 19;419(6904):269-70. doi: 10.1038/419269a. PMID: 12239558.

3 Popa I, Barborica A, Scholly J, Donos C, Bartolomei F, Lagarde S, Hirsch E, Valenti-Hirsch MP, Maliia MD, Arbune AA, Daneasa A, Ciurea J, Bajenaru OA, Mindruta I. Illusory own body perceptions mapped in the cingulate cortex-An intracranial stimulation study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019 Jun 15;40(9):2813-2826. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24563. Epub 2019 Mar 13. PMID: 30868705; PMCID: PMC6865384.

4 Scheffers M, Hoek M, Bosscher RJ, van Duijn MAJ, Schoevers RA, van Busschbach JT. Negative body experience in women with early childhood trauma: associations with trauma severity and dissociation. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017 May 31;8(1):1322892. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1322892. PMID: 28649300; PMCID: PMC5475325.

5 Rabellino D, Harricharan S, Frewen PA, Burin D, McKinnon MC, Lanius RA. "I can't tell whether it's my hand": a pilot study of the neurophenomenology of body representation during the rubber hand illusion in trauma-related disorders. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016 Nov 21;7:32918. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.32918. PMID: 27876453; PMCID: PMC5120383.