Parenting

5 Reasons I Won’t Say "Should" to Myself or My Son

How ditching one word made me feel happier, healthier and more secure.

Posted December 15, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- When we tell ourselves we “should” do something, it holds us to a standard we might not be able to meet and can make us feel inadequate.

- "Should" can carry implicit criticism and can cause people to feel shame.

- Telling ourselves we "should" do something can create anxiety and increase stress.

I checked the weather app on my phone. It’s 41 degrees and windy. I groaned and got ready, but not for the cold.

“Marty!” I yelled to my nine-year-old son. “We’re running late!”

Marty appeared at the front door in shorts, a t-shirt and slides. No socks. No jacket.

“It’s freezing outside,” I said. “You should wear a coat.”

“You’re the one that gets cold,” he said. “Not me,” and walked out the door.

I reminded myself to stay calm.

But Marty’s choice to be chilly often triggers me.

It’s not about clothing as much as compliance. And the idea that I ought to be able to make my kid do what I think is right.

Kids should listen to their parents, right?

Is “should” bullsh*t?

“Should” isn’t necessarily a bad word. It can represent a reasonable standard. But that norm doesn’t take into account someone’s life experience, perspective, or ability.

It feels critical, not compassionate. It’s a word that functions like a weapon. Loaded with value judgments that leave me angry at my child and finding fault with myself.

Let’s be real. I can’t control whether my kid wears his coat.

I’m a mom, not a magician.

“Should” is judgmental

As Marty and I walked down the street, neighborhood moms can’t help but comment.

“He shouldn’t be wearing shorts!”

“You should get him a jacket!”

“You shouldn’t let him walk around like that. He’ll get sick.”

My son spends too much time on his iPad. He dresses for Miami when we live in New York City. He sneaks a cookie before it’s time for dinner.

My reality is not someone else’s fantasy.

Best-selling author Judith Warner wrote Perfect Madness: Motherhood in the Age of Anxiety, a book about being a mom in our culture of perfection. She says the word “should” is oppressive and prevents us from feeling good about ourselves. “Nobody’s life is what it ‘should’ be,” she wrote.

“Should” makes me focus on what isn’t—instead of appreciating what is

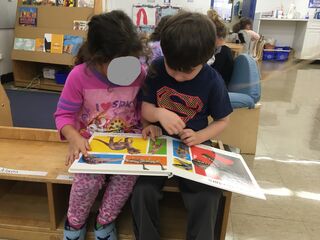

When Marty was in preschool, he could name every dinosaur of the Late Cretaceous and read about them in My First Big Book of Dinosaurs, but he couldn’t calm down for Circle Time.

“Marty isn’t sitting quietly the way he should,” his 20-something preschool teacher said in a voice without empathy.

“He’s four,” I said. “He has an active body.”

“Are you setting limits at home?” she asked, adding “You should be stricter.”

I got furious at Marty. And then at myself: If I were a better mom, my son would sit crisscross applesauce on demand.

Over time, I realized that Marty’s teacher must have missed the lecture on brain chemistry and child development when she got her degree in preschool education.

Many kids develop unevenly, excelling in certain areas while lagging in others.

Dr. Eileen Kennedy-Moore, a child psychologist and author who writes about kids’ feelings, encourages moms to be kind to themselves when they assess the strengths and challenges of their children at any given moment. “We need to see our kids with loving eyes, both where they are now and where they could grow and think about the next step. Not attending Harvard, but what is the next step?”

“Should” makes me feel rushed. As if Marty needs to do everything right. Early. Often. If he’s not, I must be doing something wrong.

“Should” doesn’t reflect what is realistic

I read a lot of parenting books and articles to help me make the best choices I can, in the hopes of parenting the way I should.

Recently I read the New York Times article, Dr. Becky Doesn’t Think the Goal of Parenting is to Make Your Kid Happy, and I came to the conclusion that I make Marty’s life too easy each morning.

“Here are your sneakers,” I say as I place them by the front door.

“Did you brush your teeth?” I ask after I squeeze blue paste on tiny white bristles and place the toothbrush on the side of the sink.

Marty should make his bed, pack his water bottle and tie his own shoes.

I should wake up earlier so that I can build more time into the routine, but I watch Money Heist and fall asleep at midnight instead.

And when the sun rises, it’s too late. I need to prep for work. The dog needs to go out. I should shower before my zoom meeting.

In the mornings, I prioritize my needs over Marty’s, which is why he wears sneakers with a Velcro strip.

Parenting isn’t as simple as I expected.

As a mom, I feel like I should be able to do it all. And do it well. Maybe I’m not doing it right, this thing called motherhood.

“Should” is based on someone else’s perception of what’s appropriate

Since I’ve started this blog, I’ve become more intentional about my parenting choices. I encourage Marty to do things that feel scary but are reasonable risks so that he cultivates courage and confidence.

One afternoon in August, Marty walked home alone from a friend’s house. It was a ten-minute walk with a short portion along a well-traveled road, with a sizeable shoulder alongside a lot of grass.

When he got home his face was bright red.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“Someone followed me,” he said as an unfamiliar car pulled into our driveway.

A concerned mom had slowed down to ask if he was okay. He had assured her that he was fine.

“I was worried,” the mom said as she rolled down her window. “I never see nine-year-olds walking on their own. So, I called the police.”

Two cars with flashing lights showed up. There were no arrests but the officers told me I shouldn’t let Marty walk home alone.

“There are too many what-ifs,” one of them said.

Marty knew the route well and felt he could do it solo. Why shouldn’t he?

Perhaps more people could let their kids go to a friend’s house without a parent by their side. What’s right for my kid may not be for everyone but does that make it wrong?

“Should” is a shackle

Long before I became a mom, I had ditched “should.”

The concept kept me caged.

Proper girls should get married. Women shouldn’t wear body armor. And Jewish reporters should not visit the Gaza Strip.

As I’ve written in earlier blogs, I broke free when my fiancé called off our wedding and I became a war reporter instead of a wife.

I did a lot of things that I shouldn’t have.

I flew illegally into Southern Sudan and camped with rebel militias fighting for their independence. I traveled to Afghanistan alone. I married a Marine I met while covering a war. We divorced.

The experiences weren’t easy and some didn’t look good on paper. But all were life-changing. I don’t regret doing a single thing that I shouldn’t have done.

Because when I stopped saying “should,” I started living in the moment. I became braver, stronger, and more authentic. I built a better relationship with myself and the world around me, based on acceptance and empathy.

Why I won’t tell my son what he "should" do

Compared to dodging bullets and bombs as a war reporter, I thought motherhood would be a breeze.

But it’s pressure-packed, with unrealistic expectations that hover like missiles looking for a soft target, like skipped homework, a jacket with the tags attached, or an unused toothbrush.

I’m tired of firing the shots and taking the hits. So, I am replacing “should” with “could,” “would” or “want.”

The other morning, snowflakes drifted down. It was the first snow of the season.

I didn’t tell Marty that he should wear his coat. Instead, I asked him why he doesn't want to wear a jacket in cold weather. I had never thought to ask.

He bent his arms, clenched his fists, and flexed his biceps to make them bulge—like Popeye.

“Grrrrr!” he said. “I feel tough.”

By braving the weather, he feels strong. It puts him in a mindset of, “I’ve got this,” to face whatever storm might come his way.

That’s more protection than any jacket he should wear.