Stress

Can I Avoid Back-to-School Stress?

Yes! How a 25-foot jump into the Salmon River helped me focus on being present.

Posted August 23, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Parental pressure can cause kids and their parents to feel stress.

- Kids who go to top-performing schools are considered an at risk group for mental health disorders like anxiety and depression.

- Finding ways to be mindful and present can help parents and kids feel more relaxed and less stressed.

The race is on.

That’s how I sum up motherhood.

I feel it every September when my son goes back to school. In my neighborhood of pressure-packed parenting and hyper-competitive private schools, the stress starts early.

My son Marty went to a play-based preschool that was more like nursery university. Little four- and five-year-olds were under intense pressure to perform.

I had no idea that I was stepping into a world where there wasn’t an instant to waste.

Why is every moment a teaching moment?

In the morning elevator ride up to Marty’s preschool, moms were too busy pushing their kids ahead to say hello. They jockeyed for the top spot, in front of the panel of numbers.

“Push five, Ezra,” a class mom implored her son.

Ezra was engrossed, playing with his plastic dump truck. But he put it down and dutifully performed the mom-requested task.

“Do you know what letter fuh-fuh-fuh- five starts with?” she asked Ezra.

He looked startled. He wasn’t prepared for a letter-recognition quiz before school started.

The not-so-friendly mom announced, “Ezra knows his numbers and he’s starting to read.” As if she should get a gold medal.

The elevator doors opened, and she rushed her future Harvard grad into his pre-K classroom, scrutinizing what the other kids were doing as she assessed Ezra’s competition for spots in the coveted elementary schools that she thought would put Ezra on the path to Cambridge.

At playdates, there were flash cards, memory games and writing tools. What happened to Play-Doh?

“Can Marty write his name?” One mom asked when he was three.

“Is he reading yet?” Another mom asked when he was four.

Pamela Schwartz, the director of my son’s preschool, told me she sees “a competition among parents,” whom, she said, know which kids can read or write. Parents are nervous about whether their kids will get into sought-after elementary schools. “Kids,” she said, “pick up on the stress of the parent.”

Dr. Joe McGuire, a child psychologist at Johns Hopkins, sees kids who are over-scheduled from the start. “There is soccer, Kumon math, violin lessons, flag football, on top of tutoring because [kids] have to get straight A’s.” Parents seem to think “to go to a good college, you need to go to a good high school and to go to a good high school, you have to go to a good elementary school. There is so much pressure.”

Early childhood is anything but laid back.

Fear of what-ifs is the norm in my neighborhood

I didn’t expect motherhood to feel so stressful. I cringe as I write these words.

On the surface, we should have it easy. But in my neighborhood of abundance, there is a perception of scarcity. As if there are only a few, limited spots that can seal future success in life. And it’s a sprint to grab one.

Raising a child feels more pressure-packed than war reporting. I should know. I’ve done both.

Parents have more fear in their eyes when they talk about kindergarten admissions than U.S. soldiers had while on patrol, in the back alleys of Baghdad.

Something is wrong with that sentence.

In war zones, courage is everywhere.

In neighborhoods like mine, fear drives us.

Neuro-psychologist Dr. Dominick Auciello works with kids as young as three. He said that too many parents think they will lose out if their child isn’t “ready for the next step” or “doing ‘it’ now, whatever ‘it’ is.” Their adult anxiety “snowballs out of control” and trickles down to the kids.

Spoiler alert: It’s not working. Studies show that anxiety and depression among kids at top-performing schools are up to three times higher than the national average because of “pressure to excel.”

When I watched this CBS Sunday Morning segment, I wanted to swap my coffee for something much stronger.

Kids haven’t changed. We have.

As I wrote in this earlier blog, childhood used to feel free. My mom wasn’t stressed over whether I met my milestones on any particular timeline. She didn’t think about my future and whether I was keeping up or getting ahead.

But forty years later, I fell into a different way of parenting.

When Marty was four, I signed him up for after-school piano, chess, Spanish, and soccer lessons, none of which he cared about.

At the time, I thought his brain was like a sponge, so why not fill it with all the things I wished I could have done—speak Spanish fluently, play piano or chess like a grandmaster, or excel in a D-I sport.

I had imposed my adult dreams, wishes and regrets on my four-year-old son, and I figured he’d thank me later.

Instead, I’m apologizing.

Sorry, Marty. You would have been better off just playing.

I would have benefitted too. Motherhood became a list of boxes to check instead of experiences to treasure.

Can I stop the stress? I need to put my oxygen mask on first.

During the school year, between work and Marty’s schedule, I didn’t have an extra second.

I took my notepad and paper to playgrounds. I did interviews in the car or in the waiting room of a doctor’s office.

My 60-minute yoga practice never went past 40. I checked emails during sun salutations. I responded to texts during savasana.

I knew I had a problem when I started to miss war reporting. It forces you to live in the present. To be part of life as it unfolds.

My summer assignment: a course correction

This summer I focused on activities for Marty that would feel liberating. I wanted him to enjoy activities without a script or specific goal.

When we went on a five-day, family rafting trip on the Salmon River in Idaho, I realized that I needed to feel that way too.

It was heaven. Nearly a week of no screens. No classes. No tutors. Just a free-flowing river in a steep canyon and 100-degree heat, a bucket for your business, and more squeals and smiles than I could have imagined.

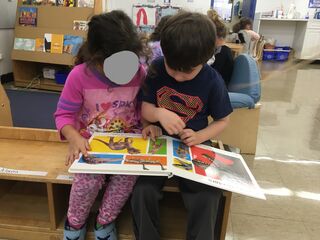

We camped on sandy beaches under shooting stars, and we watched 10-year-old kids who had just met, play as if they were BFFs since birth.

On Day Four, the guides steered our rafts to a steep cliff-wall adjacent to the river, accessible only by a series of massive boulders.

“We are rock jumping,” the always-smiling guide Mariah announced as she ascended to a ledge that looked 25 or 30 feet high.

I’ve covered wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and spent two weeks with militia groups in Southern Sudan, but there was no way I was going to jump off those rocks. I couldn’t imagine Marty would do it either.

A 25-foot fall into courage

Ten-year-old Renée went first. She squealed with delight. Eleven-year-old Anna jumped next, but came up crying. She got the wind knocked out of her. There were tears, but not of joy.

“I’m next!” a nine-year-old boy yelled.

My nine-year-old boy.

I looked up and saw Marty run and launch himself up like a rocket into empty space. As he fell, he looked like a ninja.

Maybe, stepping into the unknown gave him a chance to reinvent himself. To become his own superhero. Courageous. Bold. Unstoppable.

He splashed into the river and came up yelling, “MOM! You HAVE to jump!”

Ugh.

I glanced at a wise woman who was on the trip with her son and two granddaughters.

“You know you are going to do this.” She said to me gently.

I climbed to the ledge just below Marty, who had scrambled up ahead of me, awaiting his third turn.

“You’ve got this mom!” Marty told me.

Ugh again.

I gave myself a three count and forced my legs to move forward and push off into the air. I was untethered and free.

In the time I spent in free-fall, I inhaled uncertainty. Discomfort. Distress. Where was the water?

Suddenly it swallowed me. I kicked hard and came up in a new coat of armor. Reborn. Filled with gratitude. Feeling as tough as nails.

Did living in the moment shift how I feel about the future?

I’m back home now and the race to get ahead is about to start. I’m considering my options. Some competition is good but too much is toxic. It’s hard to find the sweet spot.

Perhaps I’ll take a page from Simone Biles’ playbook and opt out of some contests for the sake of my mental health.

I also want to be mindful of my ego. What function does it serve me to focus on Marty’s future when he’s only nine? He needs to develop confidence and pride his own way, without me keeping score or stressing out.

When I’m calmer, Marty is too.

I’m going to slow down. Enjoy the small moments. Forget the future.

Maybe Marty will thank me later. I'm trying not to care.

3 Tips to Reduce Back-to-School Stress

- Preview the day: Go over the day’s activities before school starts. Parents might consider sharing their plans first, as a way to lead by example. Discussing potential situations, feelings and possible reactions is another way to set kids up for a successful school day.

- Make mornings calm: Establish a routine so your kids know what to expect each morning. Listen and validate your child’s thoughts and feelings. Don’t pressure kids for any specific answers. Just let them know you are supporting them.

- Unschedule kids: Studies like this one show the benefits of free play for kids. Consider keeping one day a week that is free and unscheduled for your child. Downtime helps kids reset and feel calmer.