Trauma

8:40 Forever: The “Stuckness” of Trauma in Dickens

Dickens understood that trauma keeps people imprisoned in the past.

Posted May 29, 2019

Rare is the person who has lived such a charmed existence that they have never experienced a trauma, an intense emotional wound. Many people recover from traumatic events, not easily, but they are able to heal and move on. Some develop Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD). Some suffer some of the symptoms of PTSD without exhibiting the full array of indications that qualify for a diagnosis. I suspect that theorizing a trauma spectrum might be a more useful way to approach trauma than naming a specific syndrome.

For people who fail to heal in a timely fashion, traumatic experiences often affect memory. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, all of the symptoms listed in category B of the diagnostic criteria for PTSD concern memory in one way or another: involuntary memories, flashbacks, dreams of traumatic events, and adverse reactions to cues that resemble the event in some way. Paradoxically, memories of traumatic events can become more engrained or vivid than other memories, or become dissociated so that a person cannot consciously remember the trauma.

Whether the memory is enhanced or repressed, it remains inscribed in bodily memory so that reminders of the trauma, including sensory phenomena, can activate the unwanted intrusion of memory. And whether this takes the form of actual flashbacks, or vivid memories that recall salient details of a traumatic event—and the difference isn’t always clear—the result is an abrupt, usually sensory, and unbidden encounter with the past. Bessel van der Kolk, a pioneering researcher in trauma studies, writes of his patients: “For most people the memory of an unpleasant event eventually fades or is transformed into something more benign. But most of our [trauma] patients were unable to make their past into a story that happened long ago.”

Trauma changes minds, brains, and bodies. Most trauma sufferers have elevated levels of stress hormone that make them hypervigilant. It can take tremendous effort for them to trust others, and some sufferers have an impaired capacity for forming close relationships. Some trauma victims feel as if they live two lives, one in which the trauma is continually taking place, and one in which they function, sometimes in a compromised fashion, in their current lives. Some experience emotional numbness much of the time, feeling alive only when re-experiencing the trauma or a situation reminiscent of it. Another paradox: for some re-experiencing the traumatic experience in flashbacks or reminder brings pleasure. Such factors might account for why some trauma victims repeatedly put themselves into situations that re-enact the trauma by creating similar circumstances.

It is clear, however, that many (probably most) who reenact their trauma in one way or another don't derive pleasure from so doing. Freud’s concept of repetition compulsion explains why trauma sufferers might put themselves in situations akin to the original trauma even though the reward for doing so is non-existent. (While many of Freud’s ideas have been discredited, many others still form a vital part of contemporary psychological and psychotherapeutic knowledge, such as the widely-accepted concept of denial). Freud thought that repetition compulsion offered victims a way to repeat a horrific experience and get it right this time. For instance, saying no to abuse that the victim accepted out of fear, confusion, or dissociation might address the sense of helplessness that accompanied the original incident or incidents.

Unfortunately, many who were abused or victimized tend to feel acute shame and blame themselves for what happened. For these sufferers, the unconscious logic is that if they can revise the experience with a different outcome, they will no longer be distressed. And some feel so devalued by whatever has happened, particularly rape victims, that their “mea culpa” takes the form of repeatedly proving how worthless they are.

We might also think about self-recrimination and self-destructive behavior as rage directed inward. There’s a tremendous amount of anger that follows a violation or some other form of trauma, and like all forms of energy, it won’t just evaporate. Van der Kolk recounts a patient who saw his friend’s head blown open while fighting in the Vietnam War. He responded by going on a destructive spree, killing innocent children and raping a woman in a nearby village. For those in circumstances that help them to resolve the trauma, however, the anger gradually diminishes (as does the intensity of memory), as healing takes place and as other emotions and concerns begin to take up cognitive and emotional energy.

One of van der Kolk’s most insightful characterizations of acute forms trauma is that it is a “failure of the imagination.” When people are compulsively and constantly pulled back into the past, to the last time they felt intense involvement and deep emotions, they suffer from a failure of imagination, a loss of the [sic] mental flexibility. Without imagination, there is no hope, no chance to envision a better future, also characterizes trauma as a failure of imagination. Without imagination, we lose hope and creativity.”

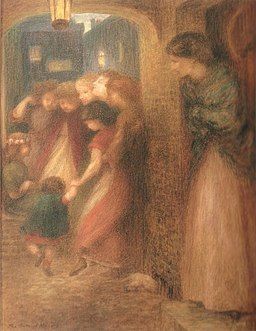

Van der Kolk might have written this sentence to describe Dickens’s Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, a brilliant depiction of the effects of trauma. Miss Havisham, a wealthy woman, arranges for a boy from the village, the blacksmith’s apprentice, Pip, to visit periodically.

The ostensible reason is so that he can be a playmate for her young ward, Estella (both children are around twelve when Pip first visits). Unbeknownst to Pip, the real reason he is summoned is so that he can fall deeply and irrevocably in love with Estella, who is being raised to be heartless. Miss Havisham hopes to break Pip’s heart, to make him suffer as she had done many years ago. Miss Havisham’s desire for revenge—a trait shared by some trauma sufferers—stems from the trauma she suffered when her fiancé abandoned her at the altar right before their wedding, at twenty to nine in the morning.

Miss Havisham offers an extraordinary portrayal of trauma. Few trauma sufferers manifest in such a histrionic Gothic mode, but the portrayal gets at the horrible “stuckness” of trauma, shared by all who have been unable to heal. It is not a description of the effects of trauma so much as it is an allegory of its psychic disruptions. Here is what Pip encounters on his first visit. His description is worth quoting at length:

In an armchair, with an elbow resting on the table and her head leaning on that hand, sat the strangest lady I have ever seen, or shall ever see.

She was dressed in rich materials—satins, and lace, and silks—all of white. Her shoes were white. And she had a long white veil dependent from her hair, and she had bridal flowers in her hair, but her hair was white. . . . .She had not quite finished dressing, for she had but one shoe on—the other was on the table near her hand—her veil was but half arranged, her watch and chain were not put on, and some gloves, and some flowers, and a prayer book, all confusedly heaped about the looking glass.

It was not in the first moments that I saw all these things, though I saw more of them in the first moments than might be supposed. But I saw that everything within my view which ought to be white, had been white long ago, and had lost its lustre, and was faded and yellow. I saw that the bride within the bridal dress had withered like the dress, and like the flowers, and had not brightness left but the brightness of her sunken eyes. I saw that the dress had been put upon the rounded figure of a young woman, and that the figure upon which it now hung loose, had shrunk to skin and bones. Once, I had been taken to see some ghastly wax-work at the Fair, representing I know not what impossible personage lying in state. Once I had been taken to one of our old marsh churches to see a skeleton in the ashes of a rich dress, that had been dug out of a vault under the church pavement. Now, wax-work and skeleton seemed to have dark eyes that moved and looked at me.”

Many aspects of a traumatic response are encompassed symbolically, in Dickens’s Gothic scenario. Above all, we see someone stuck in the traumatic moment: Miss Havisham cannot make her experience into something that happened in the past. Miss Havisham literalizes the psychic immobility of traumatic experience by stopping her life at the moment she received the news of her abandonment. We later learn that all the clocks in the house are set at that moment as well: twenty minutes to nine. Like many who suffer from trauma, everything remains as it was, but of course it doesn’t. Time might stop psychologically in that Miss Havisham ceases to participate in life at that moment, but the condition of her body and environment (there’s a particularly disgusting wedding cake moldering in another room) shows that time goes on.

She has endured a psychological death akin to the numbness felt by many trauma sufferers. Miss Havisham is a zombie in psychological terms, one of the living dead, a state of being richly conveyed by Pip’s memory of waxworks and skeletons. An expression used today that means being dumped by a romantic partner is particularly appropriate to Miss Havisham: She has been "ghosted."

The rage Miss Havisham feels is directed both inward and outward. She hopes to avenge her wrongs through Pip’s broken heart, but she also punishes herself through this ghostly existence. As with many trauma sufferers, it’s difficult to distinguish punishment from repetition compulsion. By punishing Pip, a representative and sacrificial male, Miss Havisham will rework the events that broke her heart, and this time, someone else will suffer. But by stopping time at the moment of her abandonment, she relives that day with every rising sun. Again, something that works symbolically within trauma is literalized. Each day ends at exactly the same time and so perhaps one of those days, one of these repetitions, her fiancé will return and time can move forward again.

Dickens also cottons on to van der Kolk’s extraordinary insight concerning trauma and the lack of imagination. For to stop the clock at the moment of her abandonment, to live this moment the rest of her life, reveals a total erasure of imagination. Not only does the clock stop, but narrative stops as well. When we meet Miss Havisham, her story has ended, and this stasis has lasted for decades. She can’t continue the story, generating events which might have brought the contact and comfort with others that is essential to healing. Our stories end at death, at least our earthly stories, and the end of narrative is yet another sign of the living death that trauma has wrought for this damaged and tragic character.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington D. C.: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Esposito, Linda (2016). Why Do We Repeat the Past in Our Relationships?: How Maladpative Patterns Become Engrained Over Time {Blog Post for Psychology Today]. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/anxiety-zen/201603/why-do-we-re…

Freud, Sigmund (1990). Beyond the Pleasure Principle. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Van der Kolk, Bessel (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York, Penguin Books.