Narcissism

Through a Glass Grandly

The Cognitive Distortions of Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Posted December 15, 2018

Jane Austen understood that personality traits, including empathy, are on a continuum. A person within the range of normative mental function might possess the exquisite power to see and feel from other perspectives of an Anne Elliot (the heroine of Persuasion), or the emotional stupidity of a Mrs. Elton, the upstart vicar’s wife who is cruel to the young and defenseless Harriet Martin in Emma. We might tag Anne as a “highly sensitive person” and position Mrs. Elton as low on the empathy spectrum, but neither demonstrates off-the- scale” or diagnosable traits. But those who completely lack empathy (yes, Mrs. Elton comes close) can be diagnosed with mental disorders. Such a lack distinguishes the “Cluster-B” personality disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). I’m going to turn to Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey to look at the cognitive distortions seen in Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD).

According to DSM-5, NPD is characterized by “[a] pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), a need for excessive admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts.” This can lead to a boasting; the conviction that she or he is special and superior and can only be understood by, or only associate with, other superior people; a distorted (enhanced) self-image; and other beliefs and behaviors that shore up the narcissist’s need to be the best.

People with NPD (lets call them narcissists) certainly lack the emotional component of empathy; they are so focused on themselves that they can’t possibly understand or sympathize with other people’s feelings. More interesting and complex are the cognitive distortions necessary to maintain a grandiose self-image. These compromise a person’s Theory of Mind (ToM), the ability to intuitively realize that people have minds whose contents can differ from one’s own, and to be able to infer what others are thinking. A compromised ToM means not only that people have difficulty “mindreading,” understanding from the perspective of others, but they also have difficulty understanding that thinking and reality don’t necessarily match.

Let’s back up developmentally for a moment using the work of Peter Fonagy to look at this deficit. ; Like many other cognitive abilities, children develop ToM incrementally. To begin with, they live in what Fonagy calls psychic equivalence mode, which means that they don’t distinguish between the contents of their own mind, the contents of other people’s minds, and reality—what’s really out there.

The ability to pass the false-belief test measures the presence of a developed ToM. A child under three generally will not be able to pass this test. Let’s say you and another person are in a room with a young child. You have a desk with two drawers. You put a chocolate in drawer A, and then your companion leaves the room. You switch the chocolate to drawer B. You then ask the child where the companion will look for it when he comes back. The two-year-old will say drawer B because that’s where the chocolate really is. A four-year-old will say drawer A because that’s where the companion thinks the chocolate is hidden. Here you have it, ToM in action!

The cognitive distortions of NPD can imprison people in more complex versions of misperception. Psychic equivalence mode means that a person might think that what others think and say must be true (internalization), or attribute their own thoughts and beliefs to others (projection); both deficits stem from their inability to perceive how feelings and motives, their own and those of other people, might influence perceptions. You need to be conscious of minds as minds to make such distinctions. People with NPD tend to project.

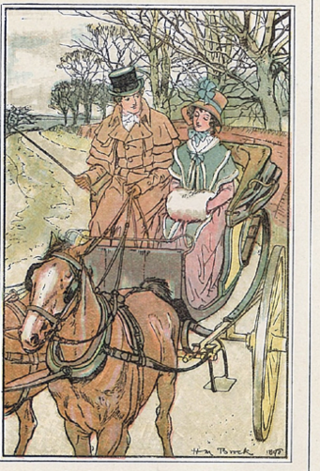

One character who clearly evinces such cognitive distortions is John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey, the oafish young man who hopes to marry the heroine, Catherine Moreland. Thorpe projects his own thoughts and wishes onto others to such an extent, and expresses views of events that are so clearly inaccurate, that he appears to have a slim grasp of reality, as we see in two episodes in which Thorpe tries to prevent Catherine from seeing her friends, the Tilneys; you might recall that Catherine is falling in love with Henry Tilney and is very fond of his sister, Eleanor. In the first episode, Thorpe asks Catherine to go on a carriage ride on a day that she has already made a date. to go on a walk with the Tilneys. Thorpe comes to Catherine’s lodgings, and when she reminds him that she has a prior engagement, he says that he has just met the Tilneys, and that they were on their way to a destination sufficiently distant to make a walk with Catherine impossible. Yet the two drive past the Henry and Eleanor walking in the direction of Catherine’s lodgings; it appears that he has lied.

John defends himself by saying that he must have seen a man who looked like Henry, and he refuses to stop the carriage to let Catherine go to her friends. Even if he thinks she will believe him (which would already indicate a slim grasp of reality), his refusal to let her explain to the Tilneys what has happened shows that he can have no idea of how his actions will affect Catherine, that he lacks mindreading skills (the ToM part of empathy). How could this possibly make her like him, which is his goal?

The walk is rescheduled, and again John tries to prevent Catherine from meeting the Tilneys in order to go on an outing with him instead. At first, he tries to persuade her to break her appointment. When that doesn’t work, he goes to the Tilneys and tells them that Catherine can’t go with them because she has a prior appointment with him. When he tells Catherine what he has done, she is furious and quickly goes to see her friends to set things right. Thorpe’s distortions further account for the major misunderstanding of the novel. But no spoilers here, in case you haven’t read this wonderful novel!

Thorpe might well be lying to get what he wants. But as I noted, this would still be such poor strategy that it points to a total inability to read minds. However, I wonder instead if he is in psychic equivalence mode to such an extent that he actually confuses wishes with beliefs. There is some evidence for this. Early on in the novel, when John takes Catherine for a yet another ride in his carriage, he contradicts himself so egregiously from moment to moment that he couldn’t possibly be keeping track of what he says. You might also account for this by saying that he is so self-absorbed and grandiose that he doesn’t care whether anyone believes his lies. So he might know he is lying, but believe he is so great that he can get away with anything, underestimating the ability of others to detect his falsehood. But there’s also the possibility that he actually believes what he says the moment he is saying it: here you have psychic equivalence.

So, to return to the carriage ride, Thorpe tells Catherine that her brother’s carriage is unsafe: “It is the most devilish little rickety business I ever beheld!—Thank God! We have got a better. I would not be bound to go two miles in it for fifty pounds.” Here we see the narcissist’s tactic of denigrating others to elevate himself. He doesn’t think that this might alarm Catherine, which of course it does, because he can’t take her perspective. And so in response to her fears and her desire to warn her brother immediately, he reverses himself: “Oh, curse it the carriage is safe enough, if a man knows how to drive it; a thing of that sort in good hands will last above twenty years after it is fairly worn out. Lord bless you! I would undertake for five pounds to drive it to York and back again, without losing a nail.” The distance from Bath (where they are) to York is almost a hundred and eighty-six and a half miles. So, first statement, he wouldn’t go two miles in it; second, he would drive it nearly two hundred miles.

I personally opt for psychic equivalence as and explanation for Thorpe's contradictions: he believes what he is saying in the moment that he says it. But I also know that the issue is undecidable from textual evidence. And I believe Austen wanted it that way. Her novels show that some people have cognitive and emotional limitations that account for their behavior, behavior that can be benign as well as malicious. And so she faced the same difficulty in determining whether the damaged people who perpetrate evil should be treated as criminals or victims. She leaves it to us to determine the extent of Thorpe’s malice, and to decide whether to condemn him, to feel sorry for him, or both. The same question is writ large in the legal and social institutions of today.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington D. C., American Psychiatric Publishing.

Austen, Jane (2001). Northanger Abbey. New York, Penguin Books.

Fonagy, Peter, Georgy Gergely, Elliot Jurist, & Mary Target (2005). Affect Regulation, Mentalization, and Development of the Self. New York, Other Press.

Jones, Wendy (2017). Jane on the Brain: Exploring the Science of Social Intelligence with Jane Austen. New York, Pegasus Books.