Narcissism

The Psychopathology of Everyday Narcissism

Jane Austen understood that pathology is on a continuum with ordinary traits.

Posted October 29, 2018

We need diagnostic categories in order to have a common language for talking about mental afflictions. But it’s all too easy to lose sight of the person if you concentrate too closely on the category.

We can minimize the drawbacks of categorical thinking by considering pathological conditions as cousins of normative states of mind, on a continuum in terms of traits. Thoughts, feelings, and actions become pathological when they reach a level of intensity or frequency that distinguishes them from ordinary variations in behavior. So, if you drink three cups of coffee a day, even if you’re addicted to those three cups and are completely non-functional without that first sip of caffeine while still in bed reading the latest novel to which you are also addicted (I might be speaking from personal experience!), you still won’t qualify for caffeine use disorder unless you have physical or psychological problems caused or intensified by caffeine, use among other symptoms.

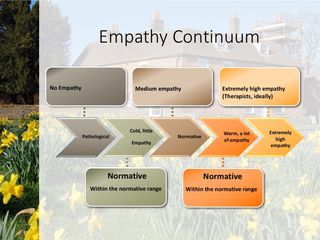

Jane Austen understood that traits are on a continuum ranging from ordinary lapses in functioning to full-blown pathologies, although she wouldn’t have used therapeutic language. As I claim in my book Jane on the Brain, Austen understood human behavior so thoroughly that we can use her work to illustrate the social mind-brain, including the self-centeredness of people, what we might call “the psychopathology of everyday narcissism.” Solipsism preoccupies Austen in all her novels, which show that even the best of us have occasions in which we can’t get beyond our own concerns and viewpoints, occasions on which we lack empathy for others. A total lack of empathy absence characterizes many of the personality disorders. Empathy includes both thinking from another person’s point of view, and also feeling from that perspective. You need both parts to have true empathy.

Even the most sensitive among us have lapses in empathy, sometimes deliberate: Therapists need to be able to turn off their empathy at times or they couldn’t cope. But a complete lack of empathy is pathological, and indeed some of Austen’s characters exhibit such a lack, becoming truly evil in their brutal disregard for others; Austen portrays such characters with clinical accuracy. But what I find just as extraordinary is that she understands the continuum between ordinary behavior and pathology: She shows how lapses in empathy can be painful to others, locating the germ of personality disorders within everyday, ordinary self-centeredness, the failure to empathize, that we all experience from time to time.

Austen’s Emma revolves around this theme of self-centeredness. Its comedy, including and mishaps and misunderstandings, and its negative underside of painful emotional experiences—being the object of scorn or rejection—are shown to stem from limitations in our ability to think and feel from other perspectives, primarily because we’re so invested in our own desires and preoccupations. The heroine Emma, although good-hearted, suffers from such limitations of empathy, and her education consists of learning to transcend these limitations, and to actively see beyond the barriers of the self.

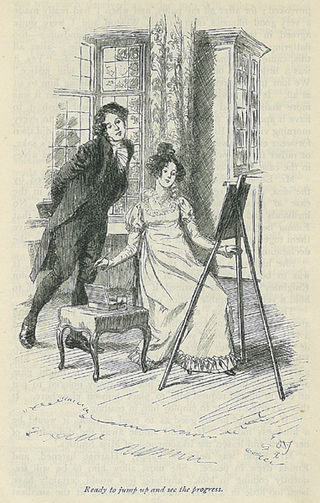

The first of Emma’s egoistical mishaps leads to a nightmare of embarrassment. Emma is so determined to match-make between her protégé Harriet and the local vicar Mr. Elton that she can’t see that Mr. Elton wants to marry her and not her young friend. Of course, she wants the best for Harriet, a young girl without family or fortune, who would benefit greatly in terms of security and status by marrying Mr. Elton. He would be a good catch! But she also wants to see herself as an accomplished manipulator of other lives. Emma bends perception to will, as we all do when we fail to see the truth because our “fictions” are so much more appealing. So when Emma suggests that she will paint Harriet’s portrait, and Mr. Elton gushes so very much about the artist and her talent, and so very little about the subject of the portrait, Emma fails to realize that she is the true object of his desire. Instead, Emma thinks to herself, “You know nothing about drawing. Don’t pretend to be in raptures about mine. Keep your raptures for Harriet’s face.”

But Mr. Elton does not keep his raptures for Harriet’s face, and it isn’t until her brother-in-law warns her that Mr. Elton appears to have feelings for her that Emma begins to notice this for herself. Invited to a dinner party that Harriet can’t attend because of a sore throat—which could be dangerous or fatal in Austen’s day—Mr. Elton barely mentions Harriet, pointedly directing his attention to Emma. For the ride home, he maneuvers the assignment of places in the various carriages so that he is alone with Emma, and she finds herself confronted with a very tipsy Mr. Elton grabbing her hand and forcefully, passionately, declaring his love. Emma is insulted that he could dare to think of her as a prospective wife, as she is well above him in social standing and has a substantial fortune. In fact, he is as far below her in wealth and status as Harriet is below him according to these criteria. Emma gets poetic justice here, although poor Harriet suffers for Emma’s mistakes.

Harriet’s heartbreak points to the dangers of solipsism, of how the failure to get over ourselves can lead to heartache for others. This lesson really comes home to Emma after the Box Hill picnic, where Emma insults Miss Bates, an older woman in poor circumstances, making her the butt of a cruel comment. Mr. Knightley, her mentor, critic, and the man she loves, raises her consciousness precisely by pointing to Emma’s failure to take Miss Bates’s perspective:

“How could you be so unfeeling to Miss Bates? . . . Were she a woman of fortune, I would leave every harmless absurdity to take its chance, I would not quarrel with you for any liberties of manner. Were she your equal in situation—but, Emma, consider how far this is from being the case. She is poor; she has sunk from the comforts she was born to; and, if she lives to old age, must probably sink more. Her situation should secure your compassion. It was badly done, indeed!—You, whom she had known from an infant, whom she had seen grow up from a period when her notice was an honor, to have you now, in thoughtless spirits, and the pride of the moment, laugh at her, humble her—and before her niece, too—and before others, many of whom (certainly some,) would be entirely guided by your treatment of her."

Notice that Mr. Knightley doesn’t scold Emma simply for the rudeness of her remark, nor does he criticize her on abstract grounds of right and wrong. He instead asks her to imagine how her remark has impacted Miss Bates, how it has likely made her feel. He paints such an accurate description of Miss Bates’s state of mind that he invites Emma to become Miss Bates for a moment.

And that’s exactly what we do when we empathize: we become someone else, cognitively and emotionally, by simulating others’ thoughts and emotions. Without such perspective taking, we would be locked in the prison house of our own feelings, needs, and points of view, a form of “solitary confinement” not as immediately painful as the literal kind, but which ultimately leads to a deprivation even more punishing: Lacking empathy, we miss out on the emotional joys and comforts that accompany authentic, close relationships, which are the birthright of every mammal, and which contribute to many of our happy endings.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association.

Baron-Cohen, Simon (2011). The Science of Evil: On Empathy and the Origins of Cruelty. New York: Basic Books.

Jones, Wendy (2017). Jane on the Brain: Exploring the Science of Social Intelligence with Jane Austen. New York: Pegasus Books.