Parenting

Parenting A Neurodivergent Child is Hard!

Self-compassion is the antidote to stress and pain

Posted August 1, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Parenting a neurodivergent child can be exhausting. The stress, the worry, the ongoing lists of extra things to monitor can seem endless.

- Feeling inadequate, ashamed and guilty are common for neurodivergent parents. Developing a sense of self compassion is the antidote.

- As a general rule, remind yourself that you are always doing the best that you can at any given moment.

Parenting a neurodivergent child can be exhausting. The stress, the worry, the ongoing lists of extra things to monitor and manage can seem endless. Often it feels like there's no spare moment to do anything other than be on constant guard for what is coming or might be coming.

It is hard for those who do not parent a neurodivergent child to understand how complex, sad, and draining it can be to see your child constantly triggered, flaring up in ways beyond the child’s ability to control and your ability to resolve.

Parents of neurodivergent children commonly report that when they share with other parents that things are difficult, the response is often, “Yes, my child also screams and has meltdowns.” This is a well-intended but confusing response, leaving many parents of neurodivergent children wondering why it is so hard for them to cope with things that other parents seem to manage just fine.

Parenting is challenging in the best of circumstances—even neurotypical children have immature self-regulation. But parenting neurodivergent children is truly a different category of challenge. One parent commented that, with his neurotypical children, most days were rewarding and every once in a while he had a difficult day. With his neurodivergent child, it was the other way around. The stress and trauma are complex and affect all aspects of wellness (emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual, and social).

Parents of children suffering from a variety of diagnoses are vulnerable to such stress. This includes parents of children with Sensory Processing Disorders (SPD), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD), conduct disorder, Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD), and neuroimmune conditions such as PANDAS/PANS/AE and many more.

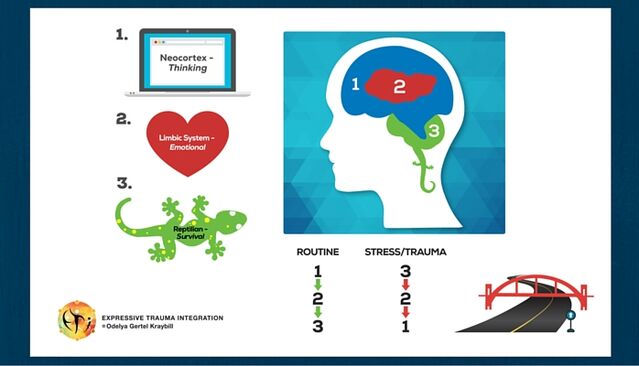

What these children share in common is this: The reptilian part of their brain is unusually sensitive and reactive. Once triggered, it persists in staying in control of brain functions longer than it should. This means that tantrums, meltdowns, or high anxiety are more easily set off and last longer than they otherwise might.

Another way to say this is that they are in 3-2-1 mode much of the time (See image below). The reptilian brain, whose primary purpose is to ensure survival in emergency situations and whose primary responses are flight, flee, or freeze, is dominant.

The world expects children, like adults, to be in 1-2-3 mode, that is, with the rational/thinking brain (neocortex) in control. Of course, adults intuitively know that children are often overtaken by emotions. But most also expect that with a little guidance, coaxing, and discipline, upset children will soon calm down.

But neurodivergent children often can’t calm down. Worried parents respond by turning up the intensity of their cajolery and discipline; children react further and become even more out of control.

When parents eventually reach out for help, they often end up with the wrong kind of therapy. Behavioral and cognitive modalities should not be the first line of intervention in most circumstances for neurodivergent children, but, in fact, they lie at the core of training and treatment for most therapists.

There’s no single modality alone that can bring the much-needed stability parents desperately seek. Behavioral and cognitive approaches have a lot to offer in working with neurodivergent children, but parents or therapists who rely exclusively on higher-brain-centered approaches inevitably get stuck. All aspects of wellness and functioning need to be considered at the same time, all the time (emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual, and social). Read more on an intervention plan in this post.

In addition, it is equally important that parents and families also address the toll of the stress and trauma that they, the caregivers, are facing as a consequence of neurodivergence.

Self-compassion as an antidote to shame, guilt, and feelings of inadequacy

Feeling inadequate, ashamed, and guilty are common for neurodivergent parents. The best strategy for living with these inevitable feelings is rather counterintuitive: Don’t try to change how you feel.

Trying to change how we feel creates a signal that something needs to be changed or fixed in us. This signal is itself so stressful that it can activate our own survival mechanism and add to the stress we carry.

It is natural of course to want to avoid discomfort, fear, or pain. But these come with life; determination to make them go away only keeps them in the center of our awareness. For most people, it works better to focus instead on expanding that which is good and increasing capacity to endure that which is difficult.

To accept the pain that life brings rather than fight it requires self-compassion. Most of us recognize the value of compassion towards others and try to be kind and empathetic towards them. But living well also requires self-compassion, directing kindness towards oneself. Neff (2003) describes self-compassion as “an emotionally positive self-attitude that [can] protect against the negative consequences of self-judgment, isolation, and rumination (such as depression)” (p. 85).

For many of us, it is difficult to feel and direct kindness towards ourselves. It is especially difficult when we feel helpless in the face of pain carried by someone we love. We want to make things better. We feel responsible to do so. When we can’t, we feel at a deep level that we are failing.

This struggle is baked into the dynamics of neurodivergent parenting. No matter how loving or skilled parents are, there is no escaping the reality that neurodivergent children often respond reactively (3-2-1) to efforts to do things taken for granted as essential to life—eating, sleeping, bathing, dressing, exercising, socializing, exploring. Virtually everything that parents do with and for their children is a potential battleground, a setting in which to experience failure and often angry rejection by a child.

Anger, frustration, and disappointment are inevitable for us. It is difficult not to judge ourselves for all the things we wish we could have or should have done differently. Many parents get sucked into a downward cycle of their own, dominated by self-criticism and constant struggle to change, to be “better,” to be “fixed”.

Self-compassion offers a path out of this trap. It does not require you to be grateful for what life has brought you, nor does it mean pitying yourself for your difficulties. Rather it means simply getting attuned to how you feel and, as you are able, honoring that feeling, without self-judgment.

The way to expand capacity to endure pain begins with being open to not being open. Try not to change how you feel, think, or sense things. Aim to be a self-observer, not a self-changer. It’s not that we want to resist change, of course, but rather that change is easier and we live more happily if we allow it to happen rather than trying to impose it.

Observe what you are experiencing. Notice what you feel stuck about and how you experience the sense of stuckness. Same with tearfulness, anxiety, sadness, discouragement. Pay equal attention to good moments. When do things improve and lighten? How and where do you experience relaxation, hope, joy?

Think of this journey with neurodivergent parenting, or whatever you are struggling with, as a research project. Put aside evaluation and judgment. Without trying to change anything, gather data on your senses, reactions, and responses.

Simplified self-compassion:

- As a general rule, remind yourself that you are always doing the best that you can at any given moment. Given a choice, you may have responded differently to this or that. But you couldn't. 3-2-1 mechanisms take over when you are stressed or afraid and react without reason. It happens to everyone!

- When you are able not to try and change how you feel, you “expand” your response to what you are feeling. When you criticize yourself you “contract.”

- When it is difficult and painful, say: “It’s ok to feel pain, it’s ok to feel this way” “I don’t like to feel this way but it is okay to feel this way.” Saying this helps your nervous system calm down. The more you do it, the more you expand your ability to relax when you choose.

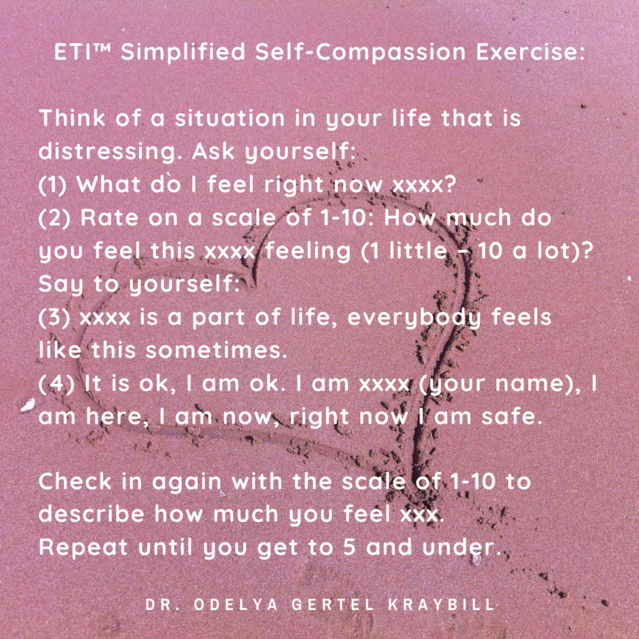

Try this ETI Simplified Self-Compassion Exercise

References

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and identity, 2(2), 85-101.