Consumer Behavior

Does Personalized Marketing Work?

5 factors can render tailored advertisements ineffective.

Posted May 4, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Personalized matching is when marketers tailor aspects of their message or its delivery to the recipient.

- Advertisement are sometimes rendered less effective when recipients respond negatively to personalized matching.

- Backfire effects fall into five categories: invasion of privacy, attempt at manipulation, unfair judgment, known content, and weak arguments.

[By Joe Siev and Richard Petty].

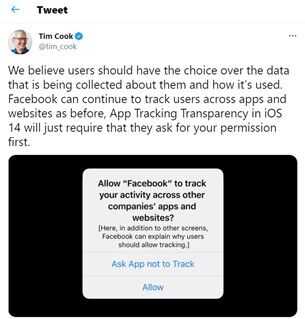

Apple’s new operating system for its popular iPhone makes it easier for people to avoid being tracked by companies that want to deliver personalized messages. Tailored advertising can range from receiving an unsolicited letter, email, or text addressed to you by name to a highly targeted banner ad based on your recent online search history.

In today’s digital economy, ads frequently use behavioral data (our clicks when web surfing) to identify and target us in numerous ways including by our gender, race, and even those shoes we searched for this morning. For internet users, this kind of personalization is everywhere.

Surveys show that many consumers have reservations about targeted advertising that might cause them to avoid such ads and resist their influence. Given how widespread personalized advertising has become, just how susceptible to influence are we?

To better understand people’s responses to personalized marketing, our research team at Ohio State University recently reviewed decades of psychology and consumer behavior research studies on the effectiveness of different types of personalization for changing consumers’ attitudes and behavior. The review is published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology.

As it turns out, although personalized marketing can be effective, it is not always effective and can even backfire. Here are some things for skeptical consumers to be aware of when it comes to personalization.

What Is Personalized Matching?

Our review covered various types of personalized matching — when marketers tailor aspects of their message, the source delivering the message, or the setting in which the message is received, to be compatible with some aspect of the recipient.

For example, in a classic study it was shown that emphasizing the benefits of a product for one’s social image is typically effective for consumers who care about making a good impression on others, but emphasizing product quality is a better bet for consumers who care less about their image. Here, the message itself matches the recipient’s goals (i.e., a message-to-recipient match).

Examples of source-to-recipient matching include showing that a Republican politician has more success than a Democrat in persuading Republican voters to support a policy (and vice versa), and that powerful (vs. low power) sources are more persuasive to powerful (vs. low power) recipients (and vice versa).

Personalization can also take the form of a setting-to-recipient match. For example, recreational shoppers tend to prefer stimulating and immersive online shopping experiences, whereas utilitarian shoppers find these features distracting and prefer a straightforward, functional user experience.

When Does Personalized Matching Backfire?

Our review of the many studies on personalized matching reinforced the view that it is often beneficial for marketers. However, we also found cases when personalized matching actually reduced the ad’s influence because consumers interpreted the match negatively. These backfire effects fall into five categories:

- Invasion of privacy. The most obvious way matching backfires is when consumers believe marketers acquired or are using personal data they thought was or should be private. Consumers with concerns about data privacy are relatively resistant to matching effects, although they may be more open to it when companies obtain consent to collect and use their data.

- Attempt at manipulation. Matching backfires if consumers believe marketers are attempting to control or manipulate them in some way. The most marketing savvy consumers are especially resistant to manipulation. Thus, learning about the psychology of persuasion can help consumers protect themselves.

- Unfair or stereotypic judgment. Matching backfires when consumers view an ad as targeting them based on an unfair or stereotypic judgment about them, such as about their gender identity, age, race, or weight. Invasiveness, manipulation, and stereotyping should be avoided for obvious ethical reasons. But sometimes matching is ineffective simply because consumers find it to be annoying.

- Already known content. Matching can make consumers tune out the message by signaling that they already know what marketers want to tell them (e.g., targeting superfans of a musician with well-publicized information about the musician’s upcoming album). Consumers with strong opinions about the matched content are especially likely to perceive it as already known to them.

- Weak arguments. Sometimes matching increases thinking about the advertisement which is great when the ad is compelling, but can backfire when the ad makes an unconvincing case.

Conclusions

Targeted advertising has come under fire recently, with some going so far as to call for an outright ban on the practice. No such bans are on the horizon, however, though some companies, like Apple, are making it easier for consumers to avoid being tracked. Although marketers’ have ethical obligations to protect consumers’ data and avoid manipulative tactics, consumers can help protect themselves through an informed approach to the psychology of personalized matching.

References

Teeny, J.D., Siev, J.J., Briñol, P., & Petty, R. E. (2021). A review and conceptual framework for understanding personalized matching effects in persuasion. Journal of Consumer Psychology. DOI: 10.1002/jcpy.1198