Intelligence

Do Kids and Adults Value Animal Lives Differently?

New research shows how our views of animals change as we get older.

Posted April 29, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Humans have various reasons for valuing some species over others.

- Researchers had adults and children of different ages rank animals from people to worms in the order they would give them a lifesaving drug.

- In some ways, the children were similar to adults in how they valued the species, but in other ways they were very different.

- There are subtle shifts in how humans prioritize different species as we develop from childhood into adults.

Yale University psychologist Lori Santos calls human thinking “glitchy”—that is, we are prone to errors and logical inconsistencies. Take, for example, our attitudes about the treatment of other species. In a Gallup poll, 32 percent of American adults agreed with the statement: “Animals should have the exact same rights as people to be free from harm and exploitation.” Yet, at the same time, 95 percent of Americans eat creatures that “should have the exact same rights as people.”

What about the moral machinations of kids? In a study by a research team from Harvard and Yale, children between 5 and 9 years old and adults were confronted with a series of hypothetical shipwreck situations in which they could save either people or dogs. In every scenario, the children were more likely than adults to save dogs rather than people. Indeed, a third of the children said they would save one dog over one person. And the adults in the study were four times more likely than the kids to let 100 dogs die to save a single human.

But at what age do children's views about the moral status of other species begin to change? Recently, Heather Henseler Kozachenko and Jared Piazza in the Department of Psychology at Lancaster University developed an innovative method to address this question by having kids and adults indicate their moral concern for different species. Their results recently appeared in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology.

What animal do you care about the most?

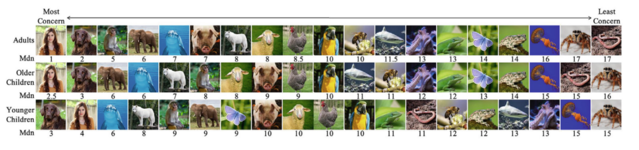

What makes their study unique is that the researchers put younger children (ages 6 to 8), older children (ages 8 to 10), and adults in a situation called the “moral rank task.” Each subject was presented with 19 photographs of species ranging from humans to worms. The researchers then instructed the subjects:

“Let’s imagine for a minute that all the animals are sick. They have a disease that is going to kill them unless we do something about it. Thankfully, we have some medicine that can help the animals get better. However, we can’t save all the animals at the same time. We are going to make some difficult decisions. Which animal should we help first?”

The participants selected the animal they would save first. Then they ranked the other target species in the order in which they would give them the medicine, from first to the last. The adults completed the task using a computer screen where they could move the images around. The kids were presented with photos of the animals on laminated cards. They would point to the card or tell the researcher the first animal they would give the medicine to, then the second, and so on until all species were placed in order, from the most worthy of getting the drug to the least worthy.

The 19 photographs consisted of eight mammals (pig, human, dog, elephant, wolf, monkey, dolphin, and sheep), two birds (chicken and parrot), two herps (frog and lizard), two insects (bee and butterfly), an octopus, a shark, a spider, a jellyfish, and a worm.

The "why" question

The researchers were also interested in the role that the attributes of animals played in the moral rankings. To address this issue, the subjects rated each of the 19 species on eight characteristics: the degree they could feel pain, their intelligence, harmfulness to humans, similarity to humans, beauty, abilities (e.g., flying, running fast), eating (whether people eat them), and edibility (how good or bad it would taste). The attributes were rated on five-point scales using icons that kids could relate to: for example, yummy faces to yucky faces (for edibility) and tiny to large brains (for intelligence).

The results: Which animal gets the medicine first

Because of my own experience talking with children about animals and the results of the shipwreck study, I anticipated that there would be substantial differences between the young kids and the older kids when it came to saving different species. In a few cases, this was true. As in the shipwreck study, most of the young kids opted to give the medicine to the dog ahead of any other species—including humans. The older kids and adults, however, tended to rank humans first and dogs second.

For the most part, however, the differences between the age groups in the rankings were not as large as I anticipated. Like me, the researchers were surprised by the similarity in the rankings of the children and adults. They wrote, “Overall, the rank order between the age groups were remarkably similar, with mammals at the top, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians in between.” (Interestingly, all three groups put bees in the middle of the pack, ahead of some vertebrates.)

Why do some animals count more than others?

But the analyses of the characteristics the subjects in the three groups used to make their moral rankings proved to be a more revealing window into similarities and differences in the moral evaluations of the participants. Among the most important results were:

- Whether a species was considered beautiful or ugly played a major role in the moral priorities of both the younger and older children and the adults.

- Unlike the kids, the moral rankings of adults were highly influenced by species’ presumed sentience (e.g., intelligence and ability to feel pain) and their similarity to humans.

- Both the younger and older children seemed confused by the concept of sentience. As Dr. Piazza told me, “They erroneously think smaller animals will feel more pain than larger animals, and they have a different understanding of what it means to be like a human.”

- Younger children were less influenced than older kids or adults by the degree to which species were similar to humans.

- Whether the species was harmful or helpful to humans played a bigger role in the decisions of the younger children than the other age groups.

- Compared to younger kids, the moral priorities of the older kids and adults were more affected by whether an animal was considered an item on the menu.

Developing moral priorities: Speciesism or more rational thinking?

I like this study because the participants were forced into making tough decisions about the relative moral status of different species. But in the real world, people have to prioritize animals all the time. Some of these decisions reflect arbitrary biases, but others are completely rational. Very few of us would agree with the animal rights advocate Joan Dunayer, who argues in her book Speciesism that you should flip a coin to decide whether to save a puppy or a child from a burning building and that termites have the right to eat your house.

The relative roles that nature and nurture play in the developmental changes in the moral priorities of children remain an open question. Some researchers argue the developmental changes in how kids think about animals reflect culturally acquired speciesism—an irrational and immoral prejudice against non-human animals. I agree that culture is a huge influence on the way we treat other species. However, I believe that the increasing cognitive sophistication of kids as they age is also important. This would explain, for example, why adults place more importance than children on species differences in intelligence and their ability to experience pain and pleasure.

The researchers concluded, “The way adults approach the valuation of animal life has its origins in early childhood, yet there is a gradual shift towards a greater appreciation of animal minds, a mentalistic notion of sentience, and the utility that animals offer humans.”

Makes sense to me.

References

Kozachenko, H. H., & Piazza, J. (2021). How children and adults value different animal lives. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 210, 105204.

Herzog, H. (2021) Do children prefer to save dogs over people. Animals and Us. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/animals-and-us/202102/why-do-ch…

Wilks, M., Caviola, L., Kahane, G., & Bloom, P. (2021). Children prioritize humans over animals less than adults do. Psychological Science, 32(1), 27-38.