Cognition

What Form Do Our Thoughts Take?

Thinking in words, pictures, both, or neither.

Posted May 28, 2024 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- The format of human thought (visual, linguistic, conceptual) is the subject of debate.

- The ability to use visual imagery and/or linguistic imagery comes in a wide variety of strengths.

- Most of us use imagery, an internal voice, or both when we’re thinking. But not everyone does.

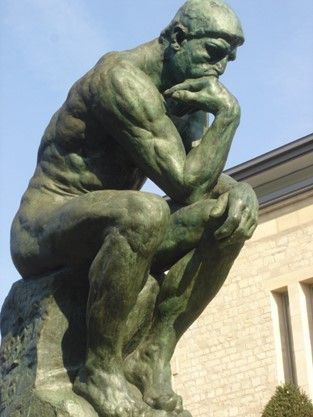

What is a thought? What does a thought feel like? Is it an image, a sound, or both? When you think, are you talking to yourself or remembering something that happened, like pulling out a photograph to examine? Or do you have an inner voice, talking to you about what is going on or what you remember?

Aphantasia

I recently discovered that a member of my extended family does not have a visual imagination. If I asked him to imagine his backyard, or dancing with his wife at their wedding, he tells me that he can’t do it. He does not have a visual image that he can pull back up and examine. This inability to picture things in his mind’s eye is called aphantasia. The name comes from the Greek phantasia meaning appearance or image and the prefix “a” from the Greek for without.

First described by Sir Francis Galton in 1880, the ability to imagine with visual imagery apparently exists on a spectrum, from people who can describe vivid, colorful, and detailed images in their “mind’s eye” to people who say they simply don’t experience images when they try to imagine something that has happened in their lives. Aphantasia isn’t considered a medical or psychological condition or disability. It's just another example of the variety of inner experiences human beings can have. Galton himself concludes that perhaps being able to “see” clear mental images might make thinking abstractly more difficult, and that those who don’t see inner images might use other sensory modalities in their thinking. He says: “chiefly I believe connected with the motor sense, that men who declare themselves entirely deficient in the power of seeing mental pictures can nevertheless give life-like descriptions of what they have seen, and can otherwise express themselves as if they were gifted with a vivid visual imagination.’ (Page 304).

If you asked my family member “did you dance with your wife at your wedding” he would tell you truthfully that he did (there are photographs to attest to the accuracy of his memory). But he gets no image of doing so. However, he says if I asked him to sketch the layout of the reception hall, or the design of their wedding cake, he would have no trouble doing so.

Anendoaphasia

There is another difference in the ability to imagine an event that has been described in the literature. According to Nedergaard and Lupyan (2024) “anendophasia” refers to the lack of an inner voice or inner speech in one’s “mind’s ear.” The name comes from several Greek roots; “an” meaning “the absence of”, “endo” meaning “internal or from within ourselves” and “phasia” referring to “language or speech.”

Many people report hearing an inner voice, often their own voice, inside their head when they think. In fact, it is so common that it has earned several names: “verbal thinking, inner speaking, covert self-talk, internal monologue, and internal dialogue” with equally numerous cognitive functions assigned to it, including self-regulation of both thinking and behavior and the development of language skills (Alderson-Day and Fernyhough, 2015, pg. 931).

Nedergaard and Lupyan were interested in the cognitive and behavioral consequences of the absence of an inner voice. They asked their participants to complete the Internal Representations Questionnaire or IRQ (Roebuck and Lupyan, 2020) which assesses auditory, visual and orthographic imagery. After separating their participants into those who report high and low levels of an inner voice, Nedergaard and Lupyan assessed performance on four different behavioral tasks. These four tasks were: (1) a test of verbal working memory, where participants were asked to recall the five words they had just seen, in the order of presentation, (2) a measure of rhyming ability, where subjects were asked whether two words rhymed or not, (3) task-switching where participants had to switch from adding to subtracting 3 to a series of numbers presented to them, and (4) a task that required participants to determine if two briefly presented images were the same or different. Performance on all four of these measures were theoretically expected to differ as a function of inner speech.

Results

Participants with more inner speech recalled more words correctly in the verbal memory task, as predicted. They were also faster and more accurate in performance of the rhyming task compared to those with less inner speech. However, the two groups did not differ in the task requiring task-switching, even when the switch was cued within the task, and they did not differ in either speed or accuracy in performance of the same/different task.

When participants were asked about how they approached solving each task, there were few if any statistical differences in the use of “talking out loud” as a strategy to solve the task. Participants who did not report inner speech were just as likely to use talking out loud as a strategy as were the “high” inner speech participants.

Conclusion

So, do we know what form thoughts take yet? Well, yes and no. Some people who seem to lack an inner voice and visual imagery report that they think “conceptually,” using what Hurlburt and Akhter (2008) called “unsymbolized thinking.” Exactly what unsymbolized thinking is like is difficult to describe, and as a result, difficult to study. But Nedergaard and Lupyan speculate that it may “correspond to a genuinely different form of experience in which people entertain more abstract conceptual representations that are less accessible to people with higher levels of inner speech and imagery” (page 15).

Most of us use imagery, an internal voice, or both when we’re thinking. But don’t make the apparently common mistake of assuming that everyone does.

Facebook image: MAYA LAB/Shutterstock

References

Alderson-Day, B., & Fernyhough, C. (2015). Inner speech: Development, cognitive functions, phenomenology, and neurobiology. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 931–965

Galton, F. (1880) Statistics of mental imagery, Mind: A Quarterly Review of Psychology and Philosophy, 19, 301-318, doi: 10.1093/mind/os-V.19.301

Hurlburt R.T., and Akhter, S.A. (2008). Unsymbolized thinking. Consciousness and Cognition, 17, 1364–1374.

Nedergaard, J.S.K., and Lupyan, G. (2024). Not everybody has an inner voice: behavioral consequences of Anendophasia. Psychological Science, Advance Online publication, doi: 10.1177/09567976241243004