Leadership

The CEO Revolution: De-Managing Organizations in Chaos

A new leadership blueprint for decentralizing and outgrowing central control.

Updated July 9, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Leading in the past was fundamentally different from leading through chaotic transformation.

- Many CEOs lead with an outdated ideology built around power and control.

- A CEO’s main duty is to harness an organization’s social forces and unleash everyone’s full potential.

I grew up in a conservative family in Indiana. My grandfather, a dedicated deacon, embodied the virtues of honesty, loyalty, and hard work. He and my grandmother, both from farming families, formed the bedrock of our tight-knit family of 50-plus people living in the same town. Their enduring 60-plus-year marriage symbolized the essence of human connection and love.

They adhered to a set of unwavering beliefs: the importance of family, devotion to divine authority, the value of hard work, respect for elders, and traditional gender roles that defined the era. These values were beautiful and functional in so many ways, but when taken too far they can get in the way of progress. This post explores the shift from leadership by authority and structure, which characterizes most of human history, to the leadership blueprint of the future.

In the past, command-and-control leadership worked well for farming. Farming values, such as my grandpa’s, played a pivotal role in the rise of large societies. They enabled humanity to surpass the limitations of hunter-gatherer bands, which were nomadic, and embrace a stationary life centered around food. While nomadic life demanded constant innovation and problem-solving, the discovery of agriculture ushered in an era of efficiency. The focus shifted from novel problem-solving to extracting food from the ground to feed the burgeoning population.

Extracting food is all about efficient coordination, and there is arguably nothing more powerful than giving people a sense of meaning and purpose. This is one of hierarchy's primary benefits. Strict hierarchies have strong values that render life interpretable and give meaning in two ways.

The first is big-picture meaning. Things like knowing where you go when you die. Knowing the vision for your future. Answering the big questions: Why are we doing this? What is the purpose of life? My family has no ambiguity in where they’re going and why they do what they do. They live for a reason, and that reason is unquestionable. It is grounding and energizing, and it galvanizes them toward a destiny, a defined future, a vision of progress and a better life.

Further, hierarchies don't just offer grand, philosophical meaning; they also give people day-to-day significance. For instance, my family lives by axiomatic obligations to each other. They have rituals such as going to church, cutting down Christmas trees in November, participating in church choir on Wednesday nights, and hanging out at my grandparents’ house on Sundays. Making sense of a chaotic world, on a day-to-day basis, is a universal need for humans. As Carl Jung said, attachment to a tradition, politic, or religion is a therapeutic necessity. The universality of religion tells us that people need to find their place in the world, experience meaning, reduce ambiguity, and avoid feelings of chaos.

Besides providing a sense of meaning, hierarchies also streamline coordination by dividing labor. Dividing labor creates specialization, focus, and enhanced teamwork. As Adam Smith said, “the greatest improvement in the productive powers of labor, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which it is anywhere directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labor.”

Each person brings their expertise to the group, creating a system that maximizes efficiency. In a farming community, one person might specialize in tending to the livestock, another in tending the crops, and yet another in cleaning machines. This division of labor saves time because each worker can focus on their specific task without having to reorient themselves to a new situation or spend time learning new skills. They can operate almost unconsciously in their area of expertise, contributing to a well-coordinated, productive community.

But organizations with traditional values struggle to keep up in today’s world of nonstop change. Organizations led by a command-and-control leader are by nature dogmatic, uncritical, and unquestioning. A critical examination of ideas is faced with bewilderment at best and hostility at worst, and challenging the status quo is a breach of loyalty to the organization’s mission. Consequently, they become very homogenous over time. Diverse thought is filtered out and unique personalities are ejected from the group, surrendering all critical thinking capacities necessary for adaptation (remember Kodak?).

This reminds me of David Foster Wallace’s seminal speech, This is Water: “There are two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, ‘Morning, boys, how’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, ‘What the hell is water?’”

Sure, no one is fully conscious of the water that surrounds them, but there is a special kind of delusion in an unquestioning hierarchy. Hierarchies foster extreme power imbalances, abusive leadership, toxic cultures, and corruption. Yuval Noah Harari, in his provocative book Sapiens, describes the discovery of agriculture as an ecological disaster and a cultural catastrophe—a discovery that led to war, hierarchy, patriarchy, slavery, and other evils.

This brings me to my central argument: leading in the past is fundamentally different from leading through chaotic transformation. I refer to this radical shift as The CEO Revolution, a seismic transition from hierarchical control to more adaptive, responsive, and innovative systems of governance.

The question is: How can revolutionary CEOs transform their organizations?

The answer is de-management. The average CEO thinks centralized management works, and that they’re good at it. They’re wrong on both accounts. The average CEO has a deep ideological incongruency. They are sure that organizations function better without government, but they reject its corollary: that their own business functions better if they stop trying to manage it.

So, what do they do? They tell people what to wear. They force employees to show up at the same time every day. They politicize performance ratings from the boss, making success dependent on an employee’s ability to fall in line and manage up. They demand that people come into the office during a pandemic. And they mandate clocking in and out to micromanage time and accumulate evidence of productivity.

The average CEO also leads with an outdated ideology, built around power and control, that is embedded in business schools. Economist Milton Friedman, for example, argued that the primary purpose of business is to maximize profit. In his famous article, The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits, published in the New York Times in 1970, Friedman wrote that executives need to serve shareholders by maximizing profit—and ignore aesthetic and altruistic concerns because they distract from making money.

But let’s remember what Napoleon said, “Do you know what amazes me more than anything else? The impotence of force to organize anything.”

The revolutionary CEO understands the impotence of rules, punishment, and leading with only power values. They know de-management is the future, and that their main responsibility is to harness the organization’s social forces and unleash everyone’s full potential—as opposed to reducing them to orders, tasks, and job descriptions.

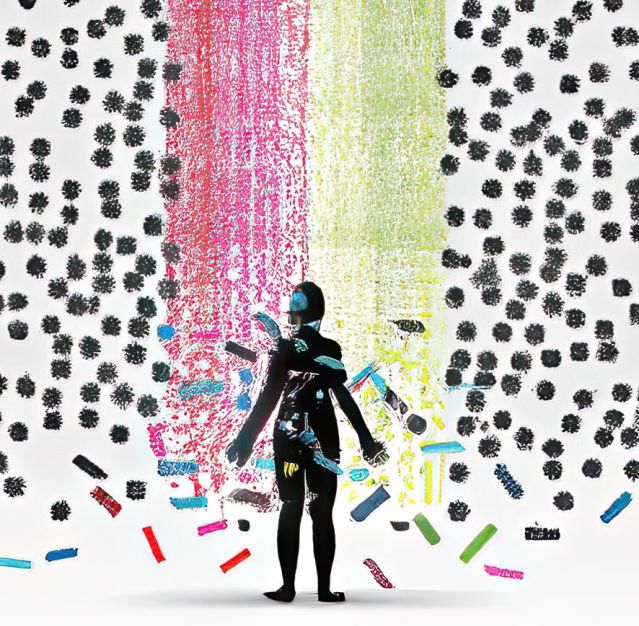

Right now, the best CEOs create aesthetic cultures of meaning and change. They don’t subject people to force but instead invite them to explore the depths of their being, encountering beauty, provocation, and emotional resonance. Steve Jobs knew artistic expressions have the capacity to touch our souls, evoking emotions, igniting imagination, and triggering moments of profound reflection. It is within these encounters that individuals find solace, inspiration, and a heightened sense of self-awareness. It is within these encounters that creativity, innovation, and change happen.

In the end, The CEO Revolution is our map into the uncharted territory of de-managing organizations and infusing aesthetics into the very essence of organizations. This bold pursuit is making a dent in humanity’s cultural evolution and setting the stage for the unfolding narrative of our collective future. And, even more, organizations have no choice in the matter. They either embrace leadership of the future or face the unforgiving consequences of natural selection. In the words of Darwin, "It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent; it is the one most adaptable to change."