Emotional Contagion

How Emotions Spread in Groups

New research helps us better understand emotional contagion at large gatherings.

Posted July 8, 2024 Reviewed by Devon Frye

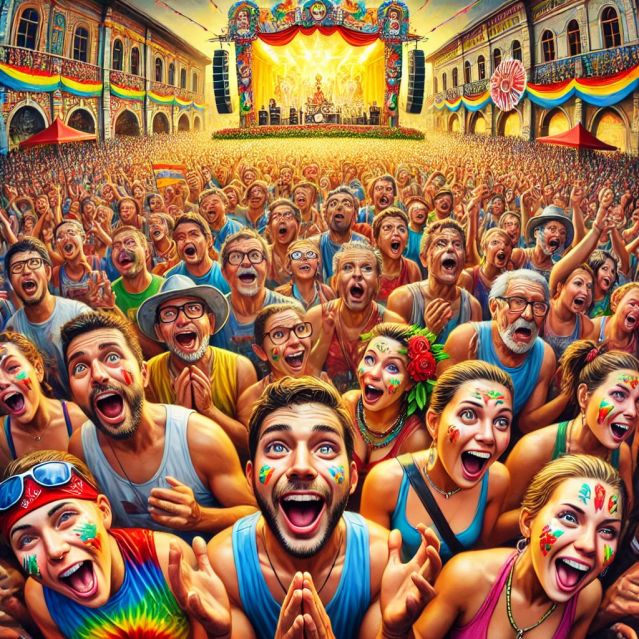

From political rallies to sports games, from public riots to religious fervor, collective gatherings can incite strong emotions. The human tendency to be transfixed and transformed in crowd contexts seems to have deep evolutionary roots.

Indeed, social scientists have argued that group gatherings may have been instrumental in the creation of the earliest human societies. The first time early humans danced around a campfire is likely to have been a pivotal moment, in which an assortment of individuals became a cohesive group.

The key to these bonding effects of group assemblies may lie in affective alignment. Writing about collective rituals in 1915, sociologist Emile Durkheim noted that these congregations do not merely generate emotions but rather bring those who share them into a stronger emotional communion.

One century later, this emotional communion was documented by empirical studies. For instance, the hearts of participants in a fire-walking ritual were found to beat in synchrony. So were the hearts of basketball fans who packed their home stadium. And, crucially, groups of fans that exhibited more synchronous arousal reported feeling more bonded with their group.

But how does this emotional synchrony come about?

In many collective gatherings, there is a distinct separation between an audience and one or more actors who function as emotional guides, like orchestra conductors. For example, sports spectators respond to the actions of the athletes, and attendees at a political rally can be swayed by the speaker’s rhetorical techniques. But although this kind of unidirectional influence is straightforward, there is much more happening in these group settings.

Members of a crowd are not merely passive receivers—they can also influence one another. This is particularly evident in collective events such as public riots, demonstrations, and religious pilgrimages that often seem to lack a clear leader, focal event, or consistent central stimulus altogether. In such contexts, emotions may seem to be infectious, spreading from person to person through contact and proximity.

Due to the public and often spontaneous nature of this phenomenon, emotional contagion through crowds has been difficult to study. In a recent study, my colleagues and I decided to measure this process by bringing technology into a real-life event: a religious procession performed in honor of the Hindu goddess Kali on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius.

The ceremony, called the Kathi Poosai, involves various stages and culminates with a dramatic sword climb, where devotees walk on the edges of old, rusty knives. Key to that event, and of primary interest to us, is a group procession leading up to that moment. During this procession, participants chant, dance, and often cry or fall into a trance, believed to be possessed by the goddess.

In this context, we asked a group of participants to wear small sensors that recorded their arousal (heart rate and skin conductivity), as well as their location through a GPS signal. We used this data to produce minute-by-minute snapshots of their position in the procession as it wound its way along the village’s coastal road. For each snapshot, we used a statistical technique called Cross-Recurrence-Quantification-Analysis to measure how similar emotional responses were between each pair.

Our findings confirmed what our ethnographic observations suggested: as the procession ebbed and flowed, proximity in space predicted emotional synchrony. The closer two people were positioned to each other, the more similarly their autonomic systems responded by regulating their heart rate and electrodermal activity. In this way, affective states were transmitted from person to person, spreading through the crowd like a wave. We had documented the process known as emotional contagion.

There was, however, more nuance to our results. While closeness was linked to emotional synchrony during the religious procession, this was not the case when the same group walked together along the same route earlier in the day to get to the starting point.

In other words, context matters. A throng of people walking down the same street may be just that: an assemblage of individuals that is merely the sum of its parts. But a group of people marching down the same street for a cause may partake in emotional communion, thanks to the shared cultural significance of the event that primes them for deeper emotional engagement.

This emotional communion lies at the core of much of what makes us human. Our tendency to congregate in dance floors, stadiums, concert halls, and temples reflects that same, deep-seated need that moved our ancestors to dance around that primordial campfire.

References

Durkheim, Émile (1915). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. London: Allen & unwin.