Midlife

Your Midlife Crisis Is Calling, Or Not

The complicated reality of middle-aged depression.

Posted October 13, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- The midlife crisis might exist and be more common in wealthy countries.

- Our resilience might determine our response to the stress of middle age.

- Even if you do go through a midlife crisis, you’ll eventually come out the other side.

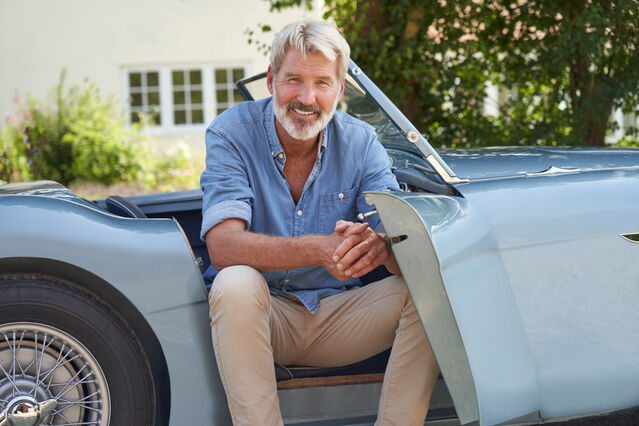

We’ve all seen the stereotypical midlife crisis: the guy in the convertible, usually in his 40s or 50s, apparently making one desperate less grasp at a long-departed youth. We assume that the car was meant to impress, but sometimes all we see is something pathetic and wasteful. We also consider this midlife crisis inevitable–as much a part of aging as receding gums or expanding waistlines.

But what if the notion of a “crisis” is not so predetermined? Midlife, sure, there’s no way to avoid a ticking clock. We all experience some physical and emotional changes as we age. And the natural uncertainty (and, for some, actual anxiety) that comes with aging is a commonplace reaction. Crisis suggests something sinister and destructive, or at the least–in the case of the convertible cliché–very expensive. A midlife crisis may reflect certain cultural norms, especially in Western society, rather than a psychological condition we all will face.

Midlife is unavoidable. The crisis might be optional.

Midlife? Global. Crisis? Local. The psychological stress that most of us face during midlife–a period which some define as aged 30 to 70, with the core years being 40 to 60–is due to a specific event (like divorce, losing a parent, or losing a job). A more generic sense of acute stress brought on simply by the number of candles on your cake is much more common in wealthy countries than elsewhere.

A UK study published in the International Journal of Behavioral Development found that 59 percent of women surveyed who were aged 40-49 reported that they had experienced a crisis. The Australian Bureau of Statistics found that those aged 45-54 were least likely to be satisfied with their lives. Other studies found no correlation between middle age and extreme distress.

It should not be a surprise to hear that truly universal human experiences (like aging) do not happen only in specific parts of the world. This phenomenon suggests that the cultural norms around aging and society’s perception of the value of people over a certain age can cause people to feel stress when they reach that milestone.

It's not all in your head. It’s not anything at all. A crisis suggests a particularly negative outcome is certain or likely, and one should take lengths to avoid that outcome. Merely turning 40 (or 50 or 60) does not create an unavoidable psychological negative event in your brain. People going through a midlife crisis have likely internalized a (probably devastating) narrative that they are declining in some critical way due to age.

For some, it’s a perceived deterioration in their intellectual capacity. According to one study cited by the American Psychological Association: “Verbal ability, numerical ability, reasoning and verbal memory all improve by midlife.” That’s right–improve. A midlife crisis doesn’t result from an actual decline in mental processing. So don’t blame your brain.

You can have crises during midlife. If a midlife crisis isn’t a mental health issue in a clinical sense, how do we explain that–at least in some countries–most people report feeling the least happy in their forties? (Age 45-46 is considered by many to be the apex of midlife).

One possibility: people during this period are part of the “sandwich generation,” one of the most difficult periods of our lives. At that stage, people often are at a point in their professional careers when they have significant responsibilities. They are more likely to be married and raising a family while their own parents begin to age, creating a collision of stress and obligations.

There is a reality to one’s physical decline–some face their first major health crisis at that age (or begin to notice smaller signs of aging like the need for bifocal glasses or the onset of arthritis). These individual events are real, and the stress they bring is not in your head. In the aggregate, the pressure can feel like a permanent (negative) shift in your day-to-day life experience.

What about that convertible? Why do some people seem to go through a crisis and others not so much? Some people perceive that they are losing value as they age, are running out of time, or have wasted the first decades of their adulthood. Their response is to “shake things up.” For some, that can be a merely expensive decision; for others, a more destructive one (hard drug use, an extramarital affair). It’s unclear why some people struggle so much in their midlife as to characterize it as a crisis. It may come down to individual responses: what impacts me like a gut punch might seem like just another Wednesday to you.

If you’re part of the Wednesday crowd, that’s good news: studies show that people who have proven most resilient in their young adulthood tend to be less severely impacted by the challenges of their forties and fifties. While some deal with these changes with unhealthy behaviors, others find it the right incentive to change careers or make other positive adjustments to their lives.

The good news is that studies show that most of us emerge from the crisis by our mid-50s. Even better news–that upswing seems to continue into our 60s. Perhaps the real antidote for the crisis is time, and the best advice is the same given to every teenager (another difficult stage of life): “you’ll understand when you’re older.”