Philosophy

Stoicism as a Fad and a Philosophy

Or should we try to be Stoic sages?

Posted August 4, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- The key promise of Stoicism is freedom from the anguish and pain associated with the vicissitudes of fortune.

- One drawback to Stoicism: If you refuse to make a deep emotional investment in anything, you may lessen the joy that accompanies success.

- Best-selling books and popular podcasts suggest a recent "Popstoicism" movement.

The self-help market is flooded with books about Stoicism, an ancient school of philosophy that emphasizes equanimity and self-mastery and that includes, among its proponents, famed Roman statesman and author Seneca as well as Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. Enter keywords such as “stoic” and “stoicism” in a search engine, and you will get: The Power of Stoicism; The Beginner’s Guide to Stoicism; Mastering the Stoic Way of Life; 5-Minute Stoicism Journal, and many others.

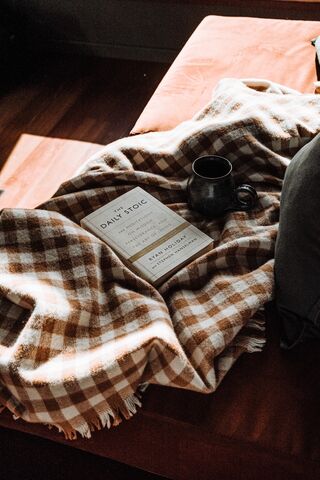

There are numerous podcasts as well, ranging from the noncommittal—e.g., Stoic Coffee Break—to those that signal hardcore fan flavor—e.g., Stoicism on Fire. And there is everything in between: Stoic Solutions; The Cheerful Stoic; The Sunday Stoic; The Daily Stoic; The Zen Stoic. It is difficult to avoid the impression that the philosophy of Seneca and Marcus Aurelius can now be tailored to suit everyone’s particular preferences, like a coffee drink at Starbucks.

Whence the Stoicism Craze?

Some suggest that Stoicism is particularly attractive now because we live in a time of uncertainty and turmoil. I doubt this explanation. I doubt it because, according to Google’s Ngram Viewer—a search engine that charts the frequency with which a word has been used in print between year 1500 and year 2019—the last year since 1500 when “Stoicism” was used approximately as often as it was in 2019, at least in English, was 1851. Even then, it did not reach quite the same level as it did recently. (The situation with the word "stoic" is even more striking as no year since 1500 rivals 2019.) If uncertainty and turmoil explain why Stoicism is in vogue, we would have to conclude that there was more uncertainty in 2019 than in any other year since the start of the 16th century. As the intervening period includes a number of famines, two world wars, the Spanish flu epidemic, and other events that killed millions, that seems unlikely.

Interestingly, it is sometimes suggested, on the other hand, that we live in a time of selfish pursuit of pleasure, so one might have expected that Epicureanism, rather than Stoicism, would be rediscovered today. Epicureans advocated the pursuit of pleasure. It is true that the ancient Epicureans regarded the pleasures of the mind more highly than bodily pleasures, but if sensory pleasure fits the modern Zeitgeist as well as they say, Epicureanism would have been adopted and customized accordingly. Yet it is not Epicureanism that’s undergoing a revival. Stoicism is. Why?

It may be that the first explanation considered is right but with a twist: while our situation isn't objectively worse than that of our predecessors, we are less able to bear the human burden and have a greater need of resilience strategies, because we've become weaker than people in harsher times were. Perhaps, that's what explains the resurgence of Stoicism. There is probably something to that, but there is likely more to the story.

A 2016 article in The New York Times titled "Ryan Holiday Sells Stoicism as a Life Hack, Without Apology" traces the beginning of the fad, at least in large measure, to the efforts of one Mr. Ryan Holiday, and a book of his titled The Obstacle Is the Way. Holiday was 27 and without formal training in philosophy when the book was published. His secret? Marketing skills. He is a public relations strategist whom the NYTimes piece quotes as saying "If you’re shameless enough, you can sell anything." His no-holds-barred approach to impression management on behalf of his clients includes, allegedly on his own admission, “forging and leaking documents, creating fake Twitter accounts and buying web traffic for blog posts he generated.” He is now selling Stoicism.

If it is, indeed, Mr. Holiday—and I can find no best-selling popular books about Stoicism before his 2014 The Obstacle Is the Way though there may be—who began what some have called the “Popstoicism” movement, that would be a remarkable fact, and one deserving of analysis. (Note: The word “stoicism” has been on the rise since 1990 so there are likely precursors. Even so, it would be interesting to follow Mr. Holiday. If he tires of Stoicism and begins to promote a different school of thought, would he succeed in starting a new trend?)

But enough about Stoicism as a fad. What of Stoicism as a teaching and a way of life?

The Promise of Stoicism

Stoicism has different versions, but the key promise—and I speak of Stoicism proper here, not of Popstoicism—is that of freedom from the anguish and pain associated with the vicissitudes of fortune. These are the rewards of a Stoic sage.

How might one achieve these things? By reassessing one’s own priorities. Human beings, on this view (which we find, in a different version, in Socrates), are to be identified not with their successes and failures, or with the strokes of good or bad luck they may experience, but with their own characters. Our characters, however, are up to us. In this sense, what matters above all else is not subject to chance.

There is a corollary idea that happiness and unhappiness do not reside simply in external events but in our reactions to events. We can gain control over our own reactions by keeping in focus what truly matters—that is, our moral characters.

There is much more to say about Stoicism (interested readers may consider taking a look at Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations), but for present purposes, this brief description will do.

There are two questions one may wish to ask here: Is Stoic sagehood achievable? And is it desirable? I will take these in the order mentioned.

Here, as elsewhere, some people will find it easier to follow the path compared to others. Our outlook on life depends on our general propensities and temperament. Much as it may be easier for a more introverted person to become a Buddhist monk, so also it may come more naturally to someone less invested in worldly success and more in moral improvement to become a Stoic.

In addition, there will be obstacles that everyone will face, to one extent or other. One is the sheer recalcitrance of human emotions. Say, you buy some stock, and the price falls precipitously, causing you frustration. You may fully believe that, in the grand scheme of things, the price fall doesn’t matter a bit, and that the money lost does not affect your life, let alone your character. Your reaction may, for all that, remain what it is, at least for a while.

More importantly, it is not always clear how what happens reflects on us. Imagine you’ve had a falling out with a friend. Maybe you think it was not your fault. But, really, you are not sure. In fact, a person of good character is often uncertain in such cases. Unfailing confidence in one’s own rightness is typically arrogance. Doubt, however, breeds anxiety. The problem is that it is often difficult to know whether or not we acted as we should have. Our characters may depend on us, but they are always in question.

Suppose, though, that a person achieved Stoic sagehood. Would that be a good thing?

There is much to be said for Stoicism, no doubt. It is certainly worth asking, in the face of loss, how much what happened truly mattered. Our minds often blow the negative out of proportion. In addition, if you learn to handle adversity, you won't fear it. If it should come, you will be prepared. Anxiety will diminish.

But there are potential disadvantages as well. Note first that if you truly want to be a Stoic, it wouldn’t do to turn to Stoicism as a last resort in times of trouble—like an atheist who becomes religious in the proverbial foxhole—and shed Stoicism when the sun is shining. The Stoic prepares for bad outcomes when times are good. The strategy is one of weakening one’s own attachments proactively.

There are two drawbacks here. First, if you refuse to make a deep emotional investment in anything, you will likely lessen the joy that accompanies success, not simply the pain of failure. Stoicism in practice, then, may be a bit like those drugs for bipolar disorder that cause emotions to flatline and help avoid the lows at the cost of sacrificing the highs. When desires are fulfilled, it counsels us to keep in mind that things could have gone a different way and might still. Victories are precarious. You must never be too ecstatic about getting what you wanted. That's how you avoid the sting of defeat if a reversal of fortune follows.

The other drawback has to do with human bonds. Some of the most unendurable losses in life involve people. It may be wise to accept with equanimity the loss of fame or fortune, but what of those we love? I once heard a story about a Buddhist meditator who was very compassionate in general but who remained unfazed by the death of his young child. What should we make of that?

Gut-wrenching as grief may be, it is the price we pay for love, and the wisdom of a path that proposes to inoculate us against grief can be questioned. It may be that a world populated by Stoic sages would be not unlike that described by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World: one where people don’t mourn the dead and, instead, use their bodies to fertilize plants.

Follow me here.