Race and Ethnicity

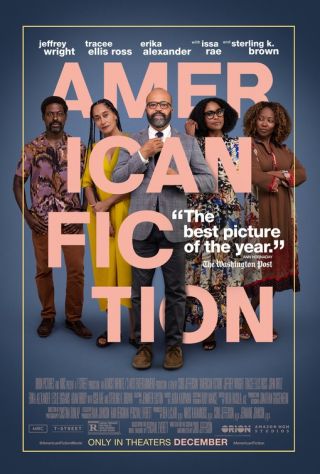

“American Fiction” Tilts at Racism, Being, and Belonging

Personal Perspective: Films provide a space to reflect on our journeys in time.

Posted December 24, 2023 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

“American Fiction” and “The Color Purple” bookend my Christmas holiday weekend. They give me a chance to be grateful for a golden age for Black American culture, and even deeper gratitude for the Black community’s spirit and collectivity, despite horrendous history and formidable current challenges. Consciousness of the journey of Black Americans brought profound meaning, inspiration, conscience, and outrage to me as a 1.8 generation immigrant (I came to the U.S. at less than 2 years old) growing up in the South and Midwest. I was inspired and troubled by TV series such as “Roots” and “Eyes on the Prize,” and both inspiration and being troubled by suffering have followed me all my years. The voices of all marginalized individuals and communities are profoundly important for the future, because our survival and growth as a nation and world depend on empathy and compassion for vulnerability. When we see each other, when we see our own vulnerability and create connection out of the disconnections of our past, we can transform our predicament into possibility.

"American Fiction” is based on the 2001 novel “Erasure” by Percival Everett, and stars Jeffrey Wright as Thelonious “Monk” Ellison. (Spoilers follow.) Monk is an African American literature professor and novelist who quickly gets into hot water when he brashly refuses to erase the “N” word when a white student demands it. “I got over it. You can too,” he says, before being called into his boss’s office and forced to take a leave of absence. Ironically, the N-word, or at least Monk’s harshness to his student, is unacceptable, while the institutional need to punish Monk is not.

And Monk feels punished in other ways. There is a subtle hint of racism when a cab passes him by for a white passenger. We are introduced gradually to Monk’s origin story. His family has had great difficulty, trauma and conflict. He was close to his father, a successful doctor who praised him, but his father was a complicated man who cheated on his mother, and ended his life in suicide by gun when Monk was a child. His mother (played by Leslie Uggams) was “not the greatest mom.” She delivers a stinging rejection of his brother Cliff’s (Sterling K. Brown) queer identity. His sister Lisa (played by Tracee Ellis Ross) conveys her resentment at the way he and Cliff left her to care for her mother. Monk is invited to speak to a mostly empty room at a book festival, where he compares his lack of financial success despite publishing several novels with the enthusiastic reception a Black woman author receives for her novel, which seems to him (and viewers) as rife with stereotypes. “We's Lives In Da Ghetto,” to Monk, seems written to fit the expectations of white editors at a Big-5 publishing house, wanting to sell to a mostly white female audience who look for racial absolution and confirmation of biases rather than a more nuanced engagement with conscience and reality.

Monk is dissatisfied with his personal journey, his own lack of creative success and inability to catch the culture’s attention. He is also annoyed with a culture that avoids thoroughgoing self-reflection by giving license to tropes; a culture that would rather satisfy a self-congratulatory need for “representation” without true change in actual racism, either in the publishing industry or in society-writ-large.

Monk feels punished, alienated, and resentful, and this turns into a cynical ploy. He writes his own stereotyped novel, “My Pafology,” and pretends to be its fugitive Black convict author in order to pitch it to a publisher. To his great surprise, what he has conceived as a truly bad novel gets picked up, demonstrating the blinkered sensibility and gullibility of the publishing industry, and what he terms an addiction to “trauma porn.”

Ironically, the film itself, and my weekend bookended by African American films, does prove that “narrative plenitude” is alive and well, for African Americans at least. Given the times and challenges, though, we must continue to question the relationship between success in the virtual worlds of film and literature and the glaring racism of our politics and culture, where nearly half of the country aggressively denies the issue altogether (thus, demonstrating it), and the other half is increasingly aware of great disparities in health, wealth, education, safety, belonging, and historical knowledge, all quite traceable to zip code and race. Black men, in particular, are under great duress and stress. The “subordinate target male hypothesis” points out how many in our culture specifically discriminate against Black males in order to achieve their goals of “winning” against vulnerable others in what they make a zero-sum game.

How can one be and belong in the face of this very specific kind of suffering? And how can one be when one feels the suffering of being talented and overlooked, deserving and yet treated unfairly beyond the ordinary unfairness of life? As Langston Hughes asked, “what happens to a dream deferred?” (See my article in references on the subject.) These questions uncover very basic needs for safety, attention, appreciation, and love, common to all, but more pressing to the most vulnerable among us. Is cultural attention and representation an adequate “reward” for Monk, or any of us? What other prize must we keep our eyes on?

Near the end of the film, Monk trades nods with a Black male actor who is playing an enslaved person. It is an ambiguous moment. We can celebrate representation and two Black men seeing each other. We can also revisit tragic memory and the unstated recognition that culture is a work-in-progress, not a done deal. “We’re here – but where have we been, and where are we going?” the two men, travelers in time, might have said to each other.

As we celebrate Christmas and welcome the New Year, I hope we can all be works-in-America’s-progress towards equity, justice, wellness, and belonging. Take gentle care, everyone, and take time to enjoy a movie or two!

© 2023 Ravi Chandra, M.D., D.F.A.P.A.

References

Chandra R. A Dream Deferred: Langston Hughes, Then and Now. The Pacific Heart blog on Psychology Today, May 30, 2020