ADHD

We perpetuate stigma when we label people as disordered

Words Matter: let's use condition instead of labelling people disordered

Posted February 28, 2021

In my field of psychiatry and addiction, stigma is unintentionally perpetuated by using words like “disorder.” Substance use disorder. Major depressive disorder. Attention deficit disorder. As soon as you diagnose someone as having a disorder, you separate and lump people into two groups: One that is ordered and one that is not. This devalues the person who has to carry the diagnosis like a burden. We all want the same thing: to simply feel valued by someone else. Using descriptors like disorder negates exactly what we are trying to do: remind someone of their value by treating them with respect. When is the last time you got angry at someone treating you with respect?

I prefer the word “condition.”

In a brilliant cartoon by the brilliant Gary Larson, a chubby boy with glasses is playing a tuba behind an outhouse. In the distance stand a small crowd of people. They have a flat expression as they look in the direction of the outhouse. From where that crowd is standing, they do not see the boy. They see the outhouse. They hear an extreme evacuation they believe is coming from inside the outhouse. You know what they think they are hearing. And it is not a tuba.

To me the outhouse represents stigma. Stigma is when we judge someone without really knowing who they are and why they do what they do. It is a stain of disgrace, associated with a particular circumstance, quality, or person. Very often stigma is shaming. Every time stigma is ostracizing.

It is ostracizing because it pushes a person out of one group and into a less respected group. That push is powered by mistrust. A stigmatized person is less valuable and not as trustworthy.

But that mistrust goes both ways. A person who feels less valued by you is less likely to trust you. Why should they? You don’t trust them?

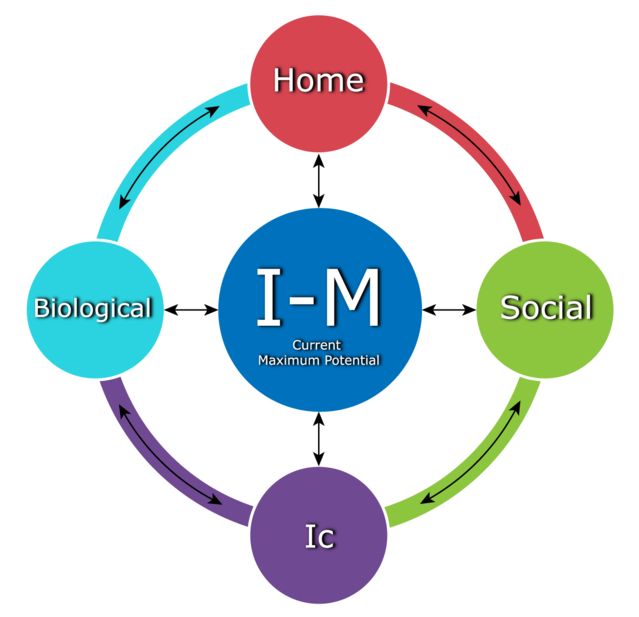

When we stigmatize and apply labels, bias, and prejudice, we will miss each other’s music. When we can only see what is in front of us, obscured by preconception, we will miss each other’s music. When we do not see a person for who they are, a person influenced by their family, their society, their sense of self, and their biology, doing the best they can, we will miss each other’s music. When we treat each other with disrespect we will miss each other’s music. When we cannot look behind the outhouse, we will miss each other’s music. We will miss the music.

A diagnosis is, after all, a convenient and abbreviated way of describing a cluster of symptoms, descriptors of behavior communicated from one observer to another observer as an attempt to draw a picture of a particular type of person.

When a patient is described as bipolar, the image emerges of a person who has, at least somewhere, sometime in their life, experienced significant shifts in mood from depressed to manic, talking fast, making big plans, euphoric, omnipotent, grandiose, accompanied by some combination of recklessness, say spending more money than one safely can, promiscuity, incredible energy and impulsive execution of impulsive plans.

If you hear the diagnosis of ADHD, you may think of a kid, usually a boy, bouncing around in a classroom, or at home, or on the playground, “hyper.” He seems oblivious to the trouble he is causing, and maybe you wonder if he is actually doing it on purpose, whatever the disruption may be.

Or borderline. Borderline. Borderline personality disorder. Now that’s a diagnosis with a bad rap. “She’s borderline.” Sort of said with one of those, you-know-what-I-mean looks and attitude, usually about a woman who you don’t like and who may actually disgust you because of how they treat others and themselves.

To “carry” a diagnosis.

What a burden.

No wonder many people resist agreeing they have an illness, a diagnosis, or resist accepting they have anything wrong at all. Such a label defines them, and usually not in a particularly flattering light but instead as broken, inadequate, compromised, weak, disorganized, bad, incapable. Untrustworthy. Disordered.

This is particularly true in psychiatry, where a diagnosis of a mental illness sends a message to the uninformed: this person is “crazy.” Mental illness still carries an enormous stigma, in fact almost an irrational fear of the irrational. As a result, many people with mental illness are often given short shrift in the community, in some sense a modern-day leper, a pariah, perhaps to be tolerated but not to be trusted.

I believe that this untrustworthiness is the core belief contributing to the enormous stigma of mental illness. Can a person who is “crazy” be a person to be trusted?

A diagnosis does not define an individual, but it can throw the pallor of mistrust on a person already in need of support, for the warm blanket wrap of security and faith that they can remain valued, trusted, embraced by their small and larger interdependent collective.

Mental illness is not a choice. No one raises their hand and says, “Oo, Oo, please give me a dose of Anxiety Disorder.” Mental illness is not volitional.

But a human being is much, much more than a diagnosis. Each of us is trying the best we can, doing the best we can, always with the potential to change, adapt, evolve.

Let's stop using the word disorder and switch to condition. Words matter.

What do you think?

References

Outsmarting Anger: 7 Strategies for Defusing Our Most Dangerous Emotion, Joseph Shrand, M.D. Leigh Devine MS, Second Printing. 2021 Books Fluid Press.