Cognition

Pain and Its Metaphors

Is there room for metaphor in the clinical treatment of pain?

Posted February 9, 2022 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Pain defies language and raises philosophical questions.

- Though it's often overlooked, there's an important aesthetic dimension to diagnosing pain.

- A holistic approach to diagnosing and treating pain would acknowledge the metaphors and benefit doctors and patients.

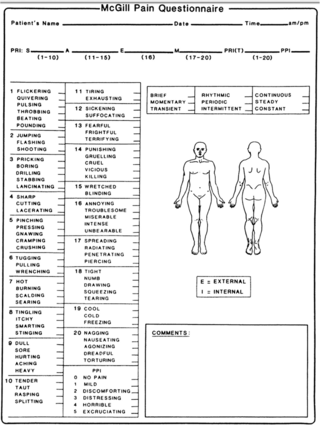

If you’re in a lot of pain, you’re likely to visit a doctor who will ask you to complete a questionnaire based on the McGill Pain Index, which gets its name from the venerable Canadian university where it was developed. Of course, pain is subjective and tends to defy language. The index is designed to find language to articulate the subtleties of pain--and generate relatively objective measures about our collective experience of physical pain.

The McGill Pain Index doesn’t just rate pain; it categorizes it. Pain can flicker, jump, drill, stab, cut, rasp, burn, or shoot.

Nearly every category of pain on the index is a metaphor. Pain is a knife, it’s a hammer, a fire, a drill, a gun, a piece of sandpaper. In cognitive terms, metaphors enable us to think in new ways about their referents. If love is a red rose, it smells sweet, but its thorns can make you bleed if you're not careful. We use metaphors for what they reveal, but they inevitably conceal, too. The red rose metaphor doesn't capture enduring love or its daily routines. A given instance of pain may feel like slicing or drilling or burning, but it's never exactly any of them—unless, of course, the person in pain is currently slicing their hand with a knife or burning it on the edge of a hot stove.

Virginia Woolf complained that “English, which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear, has no words for the shiver or the headache: The merest schoolgirl when she falls in love has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind, but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.”

The McGill Pain Index was launched in 1971, 30 years after Woolf’s death, but she would surely ask some difficult questions about it today. How can people know how to rate pain on a scale of 1 to 10? In relation to what? The history of our own pain? The pain of others? How might the pain in Keats's lungs (tuberculosis) have compared to her own migraines?

In her highly influential book, The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry remarks, “Whatever pain achieves, it achieves in part through its unsharability, and it ensures this unsharability through its resistance to language.” We can’t share pain. It reminds us that we’re alone with our pesky subjective experiences. Based on this, Scarry observes that another person’s pain is always doubtful. We can’t share it, so we can’t believe it, not viscerally. Our own pain, she writes, is “a certainty.” We know it. It dominates us.

But we can share pain, through metaphors. Though it's seldom acknowledged in a clinical setting, the McGill Index prompts doctor and patient to collaborate in an aesthetic exercise. They examine and weigh the relative accuracy of common metaphors for pain. In the process, they determine the relative efficacy of each metaphor in the service of diagnosis. In practice, though, it's easy to overlook, or conceal, the index's subtext: that pain is as philosophical as it is physical.

In two short stanzas, Emily Dickinson captures the philosophical dimension of physical pain:

Pain has an element of blank;

It cannot recollect

When it began, or if there was

A time when it was not.It has no future but itself,

Its infinite realms contain

Its past, enlightened to perceive

New periods of pain.

Poets like Dickinson and philosophers like Scarry remind us that pain is an obliterating certainty. It dominates consciousness. It suspends time. It sees itself everywhere. But when we atomize it, with the McGill metaphors, we fill in the blanks and interrupt the infinity. That’s what aesthetic experience does: It hijacks consciousness with experience created through engagement with an artist’s tools for simulating experience in paint or words or video.

In that sense, the McGill Pain Index is a step toward finding the language for pain whose absence Woolf lamented. A holistic approach to diagnosing and treating pain would acknowledge the metaphors. If doctors were to say, "Let's talk through this list of metaphors together," they would offer patients the opportunity for agency in relation to their suffering. They would frame treatment as a collaboration between doctor and patient.

Rather than simply asking a patient to make an absolute declaration that pain belongs to a single category—that it either burns or drills—a protocol that addresses the metaphorical component of pain might work more like negotiation. The pain, doctor and patient might decide, has a buzzing quality, but also burns around the edges. They would address the fact that the experience of pain is both physical and philosophical—that the physicality of pain lands people in the realm of the philosophical, asking eternal questions about what pain means, the same questions raised by writers like Woolf, Scarry, and Dickinson.