Memory

The "I Remember" Memory Technique

Joe Brainard documented his times. You can too.

Posted November 9, 2020

"I remember DDT."

"I Remember Marilyn Monroe's softness in The Misfits."

"I remember when polio was the worst thing in the world."

—Joe Brainard

The technique Joe Brainard invented in his cult classic I Remember is brilliant in its simplicity—a formula that makes anybody a good writer. Each line of the book begins with the words "I Remember," followed by a description of a memory. It's a formula for elegant sentence structures packed with insight. In countless courses and workshops, I've witnessed writers and non-writers alike adopt his technique to chronicle their times and their lives—and perhaps most importantly, the relationship between their lives and times.

As his friend Ron Padgett suggests in the Afterword to the 2001 Granary edition, "Few people can read this book and not feel like grabbing a pencil to start writing their own parallel versions." In 2020, Brainard's method offers a valuable model for documenting personal accounts of the terrifying uncertainties, daily realities, and coping strategies that define individual and collective life as we've learned to adapt. As Padgett writes,

"the most successful versions of I Remember—by both children and adults—show the same qualities as Joe's original: clarity, specificity, generosity, frankness, humor, variety, a rhythm that ebbs and flows from entry to entry, and that sense that no member is insignificant."

If you try it, I think you'll find your own version of Brainard's clarity, specificity, variety, and rhythm flow from your mind to the page. I suggest starting with 10 entries or memories. See where it goes. If you feel like it, send it to friends or family. Invite them to exchange "I Remember" lists. Soon, you'll accumulate a chronicle of the times we're living through—and the weeks, months, years, and decades that came before, shaping our experience of the now.

When Brainard writes, he's always in more than one time. He's remembering in the present of the writing, layered onto the pasts conjured by his memories. He published a slim edition in 1975, followed by three sequels, including one entitled I Remember Christmas.

In 1975, he assembled and published the Full Court Press edition, comprised of material from all these editions. The memories he recounts range from his early childhood in the 1940s, his teen years in the 1950s, and young adulthood in the 1960s. As they accumulate, his highly personal voice starts to feel collective, like a time capsule that represents cultural evolution as much as one man's experience. Brainard's book has influenced numerous artists continuously since then, including Avi Zev Weider and David Chartier's short film adaptation (starring John Cameron Mitchell).

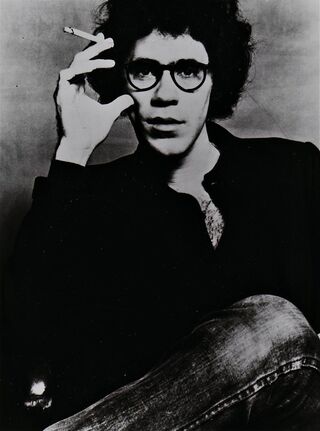

Brainard, who died of complications of AIDS in 1994, was a highly successful visual artist. His art, like his writing, was both mischievous and philosophical. No topic was too mundane, too taboo, too embarrassing, too sensitive, or too fanciful. Here are some examples:

"I remember Oreo chocolate cookies and a big glass of milk.

I remember when I was very young getting what I now assume to have been an enema. I just remember having to turn over and my mother sticking this glass thing with a rubber ball on top (also pinkish-red) up my butt and being scared to death.

I remember the day John Kennedy was shot.

I remember my father in blackface, as part of a minstrel show.

I remember wondering what the bus driver was thinking about.

I remember wondering if I looked queer."

It's possible Brainard's method works so well because he anticipated some key tenets of contemporary memory research: memory's subjective qualities, its layered and often unreliable relation to past experience, and its dependence on what memory researcher Daniel Schacter calls "retrieval cues"—the catalysts that stir memory or make it possible. For example, when I look at a family photo, I may remember a family dinner, an argument, or a poignant moment. Without the photo, I won't experience the memory, at least not at that moment.

In his book, Searching for Memory, Schacter writes, "Because our understanding of ourselves is so dependent on what we can remember of the past, it is troubling to realize that successful recall depends heavily on the availability of appropriate retrieval cues." In other words, our memories of the past depend on—are wrapped up with—our experience in the present.

Schacter observes that "it is often assumed that a retrieval cue merely arouses or activates a memory that is slumbering in the recesses of the brain." He argues, instead, that a retrieval cue "combines with the engram to yield a new, emergent entity." An engram, by his definition, is "the memory trace" in the brain—"the enduring change in the nervous system that conserves the effects of memory across time."

I Remember is a book of engrams upon engrams. As a narrator, Brainard blends his current and past experiences to present a set of curated memories. Though we may question the accuracy of a given memory, his method is a more truthful representation of the workings of memory than it would be if it pretended to be a list of memories "merely aroused or activated" in the form of facts.

Facts matter. We need journalists and historians to tell the stories of 2020—a global pandemic, economic crisis, political division, environmental disasters, racism, violence, and any number of existential threats. But the memories of the rest of us are just as important. We need the subjective accounts of what 2020 has felt like. We need memories that layer the present and past.

In addition to all that, "I Remember" lists can be a way of coping. Some may be revelatory; some may be fun. They may be shared or kept private, creating opportunities for connection or reflection.