Dreaming

Dickens's Magic Lanterns: Christmas for Capitalism

How did a gothic horror story become a Christmas classic for a capitalist world?

Posted December 20, 2019

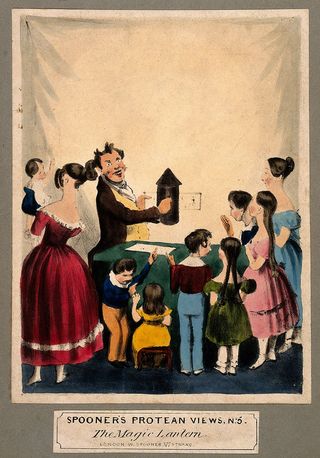

How did a gothic tale about ghosts become a Christmas classic? While debates about whether Dickens "invented" Christmas dominate headlines, another feature of his story gets overlooked—its connection to nineteenth-century "magic lantern" shows. Dickens borrowed from magic lantern artists, who used light and paper to create phantasmagoria—sensational gothic displays of specters designed to induce terror—and sometimes intended to trick audiences into thinking they were witnessing actual ghosts.

The effect was haunting, and it proved to be a powerful influence on a culture rapidly transforming along industrial capitalist lines. Dickens used a form of entertainment known for its haunting effect and made use of gothic horror to create an inspiring holiday story that would become astonishingly popular—and influential. He used magic lantern techniques to hijack his readers' minds—and to haunt us to this day. The haunting is in large part about the contradictions of "the Christmas spirit" in a capitalist world.

Before I go further, let's set the record straight. Did Dickens "invent" Christmas? Lots of headlines and a popular film suggest he did. While A Christmas Carol played a big role in how we celebrate Christmas, the rumors of its influence are a little inflated. It's true that the aristocracy had stopped hosting elaborate festivals to celebrate Christmas, and this influenced the middle classes. In his book, Charles Dickens and Christmas, David Parker, former curator of London's Dickens Museum, makes it abundantly clear that most ordinary people in Europe celebrated Christmas in their homes and communities.

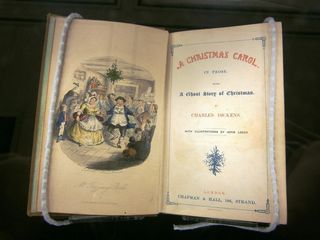

Nonetheless, Dickens's haunting parable about greed in an industrializing world has influenced the cultural meaning of Christmas. As The Guardian's John Mullen observes, the original book was "a delightful festive object as well as a topical tale," with a "splendid red binding and expensive illustrations." It was a book to be held, read aloud, passed around. It became a cultural sensation and reignited Christmas passion among the upper classes.

In her essay, "Dickensian 'Dissolving Views': The Magic Lantern, Visual Story-Telling, and the Victorian Technological Imagination," Joss Marsh documents the influence of magic lantern shows on Dickens's writing—including his portrayal of ghosts, the language and images he uses to describe how characters see, and the ideas about transformation that save Scrooge from eternal misery. Lanternists, as they were called, traveled Victorian England with their lamps and projection systems, putting on shows that were the precursors to early film. Their "magic" was making images move, in Marsh's words, "by all means possible: illusion and speed lines; panoramic 'sliders' that pushed across the beam of light; 'slipping' glasses; levers; ratchets and 'eccentrics'; pulleys; sometimes all of them at once."

As part of its Dickens on Film project, BFI Films created a short documentary on Dickens and the magic lantern—including some really great demonstrations of what magic lantern shows looked like.

In her essay, Marsh focuses on the artistry of the dissolve, "whereby light was slowly stopped down on one lens and one image and brought up on another, with perfect registration, so that the second image slowly—almost magically—replaced the first on the illuminated screen." The dissolve is familiar to us from movies. But what's ubiquitous today was a revelation for Victorian audiences. As it turns out, that revelation seems to have been a direct influence on Dickens when he wrote about the famous ghosts who treat Ebenezer Scrooge to visions of his past, present, and future.

Dickens's stories were often adapted by lanternists for their shows, but the influence went both ways. Dickens adapted the dissolve in his novels—and with his genius for concrete description, the famous realist wrote some passages I'm tempted to describe as proto-surrealism. The first of these involves the appearance of Marley, Scrooge's long-dead business partner:

Now, it is a fact, that there was nothing at all particular about the knocker on the door, except that it was very large. It is also a fact, that Scrooge had seen it night and morning during his whole residence in that place; also that Scrooge had as little of what is called fancy about him as any man in the City of London, even including—which is a bold word—the corporation, alderman, and livery. Let it also be borne in mind that Scrooge had not bestowed one thought on Marley, since his last mention of is seven-years' dead partner that afternoon. And then let any man explain to me, if he can, how it happened that Scrooge, having his key in the lock of the door, saw in the knocker, without its undergoing any intermediate process of change: not a knocker, but Marley's face.

Marley's face. It was not in impenetrable shadow as the other objects in the yard were, but had a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar. It was not angry or ferocious, but looked at Scrooge as Marley used to look: with ghostly spectacles turned upon its ghostly forehead. The hair was curiously stirred, as if by breath or hot-air; and though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. That, and its livid colour, made it horrible; but its horror seemed to be in spite of the face and beyond its control, rather than a part of its own expression.

As Scrooge looked fixedly at this phenomenon, it was a knocker again.

As in a lantern show, the knocker dissolves into Marley's face, a "dismal light" illuminating it when all else is "impenetrable shadow," and then dissolves again, back into the knocker. This happens near the beginning of the novella, almost as if Dickens is priming his audience to imagine his ghosts in the form of the familiar imagery of lantern shows.

The second instance of lantern imagery is creepier: Dickens's description of the first spirit, known to most of us as "the ghost of Christmas past":

Light flashed up in the room upon the instant, and the curtains of his bed were drawn.

The curtains of his bed were drawn aside, I tell you, by a hand. Not the curtains at his feet, nor the curtains at his back, but those to which his face was addressed. The curtains of his bed were drawn aside; and Scrooge, starting up into a half-recumbent attitude, found himself face to face with the unearthly visitor who drew them: as close to it as I am now to you, and I am standing in the spirit at your elbow.

It was a strange figure—like a child: yet not so like a child as like an old man, viewed through some supernatural medium, which gave him the appearance of having receded from the view, and being diminished into a child's proportions. Its hair, which hung about its neck and down its back, was white as if with age; and yet the face had not a wrinkle in it, and the tenderest bloom upon the skin. The arms were very long and muscular; the hands the same, as if its hold were of uncommon strength. Its legs and feet, most delicately formed, were, like those upper members, bare. It wore a tunic of the purest white; and round is wast was bound a lustrous belt, the sheen of which was beautiful. It held a branch of fresh green holly in its hand; and, in a singular contradiction of that wintry emblem, had its dress trimmed with summer flowers. But the strangest thing about it was, that from the crown of its head there sprung a bright clear jet of light, by which all this was visible; and which doubtless the occasion of its using, in its duller moments, a great extinguisher for a cap, which it now held under its arm.

The analogies to a magic lantern show are explicit: the drawing of the curtains, the sudden light, the hybrid figure of the child who is also an old man, and especially that "bright clear jet of light" springing from the crown of the spirit's head.

Dickens does something particularly odd in this passage. His narrator addresses the reader directly—and physically. The visitor, he tells us, is "as close to it as I am now to you, and I am standing in the spirit at your elbow." As one of my students pointed out, this may be a reference to the physical book the reader would be holding. This is a cool idea—and an excellent insight. I think Dickens does want us to think about the book as an object, but he also puts us in Scrooge's position. He haunts us with that spirit by asking us to imagine it standing at our elbows. It's only a little stretch to say that he wants to spook us with our relation to the capitalist greed Scrooge represents. Dickens couldn't have predicted the capitalist frenzy Christmas would become, but he does portray the chilling irony of holiday feasts celebrating Christian ideals in a world where people are starving. The ironies and contradictions of Christmas have become a mainstay of Christmas films. Think It's a Wonderful Life, The Bishop's Wife, Elf, or Last Holiday.

Marsh concludes that Scrooge's sudden transformation from greedy misanthrope to compassionate philanthropist works something like the dissolves of the magic lantern shows. It's not realistic, because it's not meant to be. That helps me see Dickens in a new way.

But there's another element to these scenes that's just as important. Scrooge is asleep when his visitors arrive, and the visions they show him resemble dreams as much as they do magic lantern shows. In a dream, it's routine to meet figures with multiple identities—Liz Taylor and your mother, for example; or "a strange figure—like a child: yet not so like a child as like an old man." Freud called this condensation—whereby two or more elements from waking life are melded in a dream.

Like magic lantern shows, dreams interrupt the routines of ordinary experience and show us the surrealism of our lives. This is why I'm now convinced that Charles Dickens was sometimes, in some of his writing, an early surrealist. Like all good surrealists, he questioned reality—in this case, the reality of industrial capitalism.

Christmas today puts us smack in the middle of a bunch of cultural contradictions. In a dream, contradictions don't matter. Surrealists reveled in contradiction. While Christmas has come to be dominated by post-industrial capitalism, it is also a break from the grind, a time for reflection, a vehicle for intimacy. As in a dream—and as in Dickens's tale—it condenses elements of life that might seem incompatible. We all need that to survive our modern world.