Anxiety

Reading Minds and News Anxiety

How Literature and Reality TV Can Help Us Cope with News Anxiety

Posted August 27, 2018

The President's former lawyer accuses him of illegal activities. A moghul denies dozens of charges of sexual assault. The world's biggest Internet corporation makes a deal with a nation it once accused of totalitarianism. A graduate student accuses a feminist professor of sexual harassment.

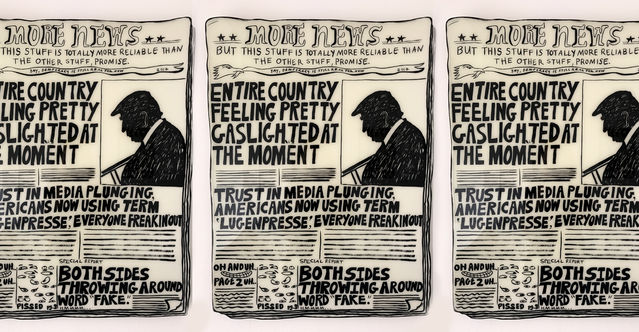

Stories like these find us whether we want them to or not. They appear on phone screens, on social media feeds, on radio and TV, and in newspapers. We talk about them over dinner or drinks. We circulate think pieces about them. Studies and surveys suggest the headlines provoke a great deal of anxiety. A psychologist has even coined the term Headline Stress Disorder.

The stories behind these headlines share an often-overlooked quality: They require readers to make guesses and draw conclusions about other people's intentions. Cognitive scientists sometimes call this mind-reading, or mentalization. What does the President's former lawyer really know? Why would a graduate student lie about harassment?

In the era of fake news, the headlines are bewildering to people of all political dispositions. I confess that for a while I felt a strident resistance to the mind reading these news stories require of us. Stop guessing about other people's motives, I wanted to shout. Stop speculating about their private lives on social media--or in credible news outlets. I had this wrong. I was wishing and hoping for the impossible. It was my version of trying to manage my unmangeable emotional response to the news. Research suggests most of us cannot help but make these guesses.

A pair of books by influential literary critics drawing on cognitive science show how literature can help us deal with the fact that the news makes mind readers of us all--Lisa Zunshine's Why We Read Fiction and Blakey Vermeule's Why Do We Care About Literary Characters? Zunshine and Vermeule even offer some clues about how we can quell the anxiety that comes with reading the news .

Zunshine explores research on "cognitive embedment" to demonstrate how writers like Virginia Woolf, Jane Austen, and Vladimir Nabokov involve readers in what she calls "mind reading"--speculating about the thoughts and feelings of fictional characters. Mind reading, she argues, is an important social skill. We can never know for sure what others think and feel, but we need to make good guesses to navigate work, love, friendship, family, and politics. She makes the crucial point that in fiction--as in life--plots often turn on the fact that mind reading involves a great deal of mis-reading. When we make guesses about other people's intentions, we often get it wrong.

Vermeule argues that "literary characters are tools to think with." Literature, she suggests, works by offering "hooks" that "capture our interest by appealing to mind-reading capacities." She extends her argument to film, reality tv, gossip--and, yes, news headlines. She makes the point that stories can work like a telescope, or like quicksand. They can illuminate the world, or they can sink us in a mire of speculation and anxiety. Brilliant reportage and fake news draw on the very same human impulses.

Zunshine and Vermeule agree that literature mirrors a basic fact of life: Humans thrive on speculating about the intentions of others. The headlines--and in some cases, the people making the headlines--are in the business of exploiting our desire to read other people's minds. It's nearly impossible to resist.

So, how to cope? Literary works offer some insight:

- Jane Austen suggests to readers that a playful attitude toward other people's intentions can help us remember that we can't know for sure what they're thinking.

- Franz Kafka reminds us that other people's minds might not work the way we imagine they do.

- Edgar Allan Poe seduces readers with apparently devious minds to show us just how often an unexpected plot twist might change everything.

- Toni Morrison demonstrates how powerful trauma and social inequity are in shaping our responses to each other.

- Virginia Woolf unravels the layers of thoughts, showing how much of our experience involves making guesses about another person's guesses about still another person's mind.

- Kazuo Ishiguro, Gabriel García Márquez, and J.K. Rowling offer vivid fictional accounts of the fact that life sometimes feels like a surreal dream. Might it feel that way for the President or his former lawyer? If so, how to we interpret their intentions?

A person who feels certain the President has committed felonies and a person convinced his lawyer is lying are both reading minds. In 2018, they're probably also circulating versions of these stories on social media. Other people are reading, responding, speculating--and getting anxious.

The history of literature is full of characters who lose themselves in fiction, getting into serious real-life trouble when they try to live like fictional heroes, from Cervantes's Don Quixote and to TV's Jane the Virgin. These characters are all really anxious, because they know they're making a mistake and can't resist. They're not humble readers. They've convinced themselves they're unfallible mind-readers. They are studies in what not to do.

In a similar vein, gossip can be a powerful social tool, but it becomes a problem when we forget that gossip is speculation, not fact. The best gossips know that when we read our neighbors' minds, we're probably doing a lot of misreading. Best not to settle too comfortably into smug conclusions. A savvy viewer of reality TV knows its characters are magnified, manufactured, and manipulated. They watch to take pleasure in reading minds that don't really exist. On her podcast Decoder Ring, cultural critic Willa Paskin makes the point that a sophisticated viewer finds pleasures in imagining the intentions behind the actors opting to play false versions of themselves onscreen (an observation very much akin to those of Zunshine's and Vermeule's). Since before the 2016 election, politics feel like they are playing by the rules of reality TV. That puts all of us in the position of reading the minds of leaders who are playing versions of themselves on TV.

So, again, how to cope? First, it's a good idea to recognize the powerful draw of mind-reading. It's just as important to recognize that these headlines are exploiting our desire to speculate about other people's intentions. If we get that far, these realizations can help us practice humility, to know that mind reading is often mis-reading. If we weren't in the room with the President or the graduate student, we don't know what they did or thought. In fact, our judicial systems are designed to deal with the fact of our fallible readings of each other's minds. They offer a process for accumulating evidence to help judges and jurors make decide how much doubt is reasonable.

When we participate in the court of public opinion, it's a good idea to be up front about the fact we're responding to headlines designed to exploit us. It's a good idea to be clear that we know we're guessing. It's also a very good idea to think twice about the extent of our participation--how often are we weighing in or circulating these stories? Are we unwittingly exploiting our friends and followers with mind-reading exercises destined to fuel anxiety? Finally, remembering Jane Austen, it can really help to take a playful attitude about the intentions of others (when possible!).