Executive Function

Why Getting Into the Groove Is Good for Your Brain

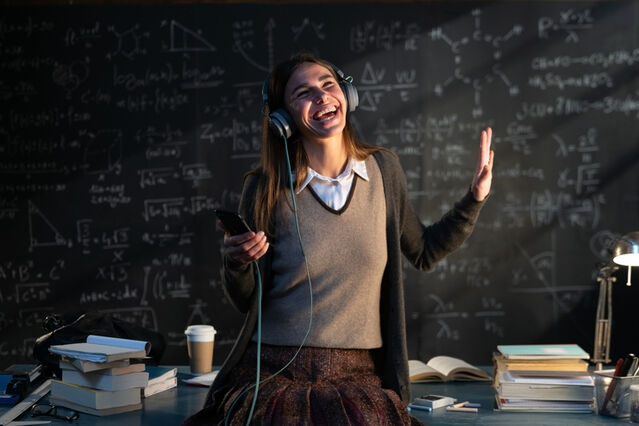

A song's rhythmic groove stimulates the prefrontal cortex in "groove enjoyers."

Posted June 13, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Listening to music that creates pleasure and arousal and putting someone in a good mood while doing cardio improves cognitive performance.

- Getting "into the groove" of a pleasure-inducing song while sitting (not exercising) enhances prefrontal cortex executive functions.

- However, a song's groove rhythm only enhances executive function if the listener experiences pleasure and is a so-called "groove enjoyer."

Music can be such a revelation. Dancing around, you feel the sweet sensation.–"Into the Groove" Madonna (116 BPM)

Over a decade ago, neuroscientists in Japan, led by the University of Tsukuba's Hideaki Soya, found (Yanagisawa et al., 2010) that aerobic exercise activates parts of the prefrontal cortex associated with better executive function and cognitive performance as indexed by a Stroop test.

Another recent study (Suwabe et al., 2021) from Soya's Lab found that if exercisers listened to songs that put them in a good mood and increased their "vitality" while doing cardio, the beneficial effects of exercise on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and executive functioning were more robust.

On the flip side, if people doing cardio only heard rhythmic beeps at a steady tempo while riding a stationary bike, they didn't self-report feeling in a better mood or increased vitality. Even though metronome beeps created a type of groove rhythm, if the person doing cardio didn't enjoy the groove, the beeps didn't stimulate the prefrontal cortex and didn't improve cognitive performance.

"Exercise with music elicited greater enhancement of a positive mood (vitality) than did exercise with beeps," the authors explained. Correlation analyses revealed a strong link between music that improved someone's mood, increased activation in the left-DLPFC, and better scores on the Stroop test. According to the researchers, "[Our] results support the hypothesis that positive mood while exercising influences the benefit of exercise on prefrontal activation and executive performance."

If a song’s groove rhythm creates pleasure and arousal, it stimulates the prefrontal cortex and enhances executive function.

In their latest experiment (Fukuie et al., 2022), senior author Hideaki Soya and colleagues investigated if hearing music with "groove rhythms" that improved people's mood could enhance executive function and Stroop scores if listeners were sitting in a chair and "wanting to move" their bodies but not doing cardio. As the authors explained,

Hearing a groove rhythm (GR), which creates the sensation of wanting to move to the music, can also create feelings of pleasure and arousal in people, and it may enhance cognitive performance, as does exercise, by stimulating the prefrontal cortex.

Interestingly, the researchers found that groove rhythms only seemed to activate the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (l-DLPFC) and improve executive function if the listener got "into the groove" and felt inspired by the music.

"In the present study, we conducted brain imaging to evaluate corresponding changes in executive function and measured individual psychological responses to groove music," Soya said in a May 2022 news release.

"The results were surprising," he added. "We found that groove rhythm enhanced executive function and activity in the l-DLPFC only in participants who reported that the music elicited a strong groove sensation and the sensation of being clear-headed."

The optimal tempo for “groove enjoyers” is 100-120 BPM.

The latest (2022) study of how getting into a song's groove rhythm stimulates the prefrontal cortex and improves executive function builds on previous research on the optimal tempo for getting into the groove. A previous study (Etani et al., 2018) found that songs with the highest groove enjoyment ratings were between 100-120 beats per minute (BPM).

On average, Etani et al. found that 116 BPM is the sweet spot where a song's groove induces the most pleasure and arousal. For reference, songs like "Into the Groove" by Madonna, "Stronger (What Doesn't Kill You)" by Kelly Clarkson, and "We Are Family" by Sister Sledge are all 116 BPM.

In Japan, the word nori is used to describe songs with a good groove that makes people want to move their bodies in a specific direction (side-to-side or back-and-forth) while sitting down. "Good nori" doesn't rely on having dance music BPMs. Songs with a slower tempo that make people want to sway from side to side can have good nori, as do more uptempo songs that make people want to move their torso back and forth (e.g., "headbanger" music).

"With regard to tempo, horizontal nori is used to embody the rhythm of pieces with slower tempi, such as ballads or other mellow songs," the authors explained. "These qualitative descriptions of nori suggest that body movement induced by music varies depending on characteristics of the music's temporal structure."

In addition to a song's temporal structure, groove rhythms that include snare drums, hi-hat cymbals, and bass-drum sounds tend to improve listeners' groove sensations.

In the 1980s, a Japanese sound engineer, Ikutaro Kakehashi, created revolutionary "Rhythm Composer" drum machines like the Roland TR-808 and TR-909. These legendary rhythm makers were capable of producing synthesized handclaps, clunky cowbells, hissing hi-hat sounds, and thunderous bass-drum sounds.

These programmable Roland drum machines can be heard on Shep Pettibone remixes of songs like "Bizarre Love Triangle" by New Order, "Too Turned On" by Alisha, and "Like a Prayer (Instrumental Dub)" by Madonna. All these tracks were Hot Dance Club Songs on Billboard's Charts in the 1980s and, in my opinion, have timelessly phenomenal nori.

Self-selected songs improve your odds of being a “groove enjoyer.”

Anecdotally, as someone who was a teenager in the 1980s, I love danceable songs with TR-808 and TR-909 rhythmic sounds. But not everyone has the same musical taste or GR preferences.

For example, Soya and colleagues found that one listener might report that a song's groove rhythm gave them a sense of "having fun," "feeling clear-headed," and "wanting to move to the music." In contrast, another listener might use descriptors like "bored," "feeling discomfort," or "wanting to stop listening" for the same song.

The key to increasing your odds of being a so-called "groove enjoyer" and reaping the cognitive benefits of a song's groove rhythm is self-selecting music that puts you in a good mood and makes you want to move your body. For tips on curating personalized playlists with groove rhythms that will boost your vitality, see "8 Ways to Maximize Music's Motivational Power."

References

Takemune Fukuie, Kazuya Suwabe, Satoshi Kawase, Takeshi Shimizu, Genta Ochi, Ryuta Kuwamizu, Yosuke Sakairi, Hideaki Soya. "Groove Rhythm Stimulates Prefrontal Cortex Function in Groove Enjoyers." Scientific Reports (First published: May 05, 2022) DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-11324-3

Kazuya Suwabe, Kazuki Hyodo, Takemune Fukuie, Genta Ochi, Kazuki Inagaki, Yosuke Sakairi, Hideaki Soya. "Positive Mood While Exercising Influences Beneficial Effects of Exercise with Music on Prefrontal Executive Function: A Functional NIRS Study." Neuroscience (First published: January 18, 2021) DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.06.007

Takahide Etani, Atsushi Marui, Satoshi Kawase, and Peter E. Keller. "Optimal Tempo for Groove: Its Relation to Directions of Body Movement and Japanese Nori." Frontiers in Psychology (First published: April 10, 2018) DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00462

Hiroki Yanagisawa, Ippeita Dan, Daisuke Tsuzuki, Morimasa Kato, Masako Okamoto, Yasushi Kyutoku, Hideaki Soya. "Acute Moderate Exercise Elicits Increased Dorsolateral Prefrontal Activation and Improves Cognitive Performance With Stroop Test." NeuroImage (First published: May 01, 2010) DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.023