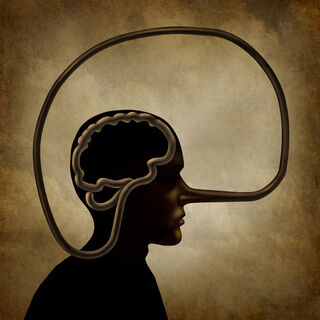

Deception

Honestly, Lying to Your Therapist Can Be a Good Thing

Five surprising ways lying can be an essential part of effective psychotherapy.

Posted March 23, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

I enter my office and press the button on my voice mail. The voice on the other end sounds rushed. Dr. Koslowitz, my sister is your patient. I know you’re not allowed to talk to me, but I’m leaving this message to let you know that I overheard your teletherapy session with my sister and you should know, she lied to you…

The joys of teletherapy with patients in small spaces. As much as we’d like to ensure confidentiality (and I can certainly do a great deal on my end—I can use a HIPAA compliant teletherapy program, I can educate my patients about online security and finding a private place to talk, among a host of other security measures I’ve learned about this year), the realities of urban living mean it’s not always possible. Apartments can be small, walls can be thin, and people can actively eavesdrop if they want to.

I found this voice message curious because it displays a certain assumption about psychotherapy that I believe many people hold—that if the patient isn’t telling her therapist the absolute truth, and nothing but the truth, psychotherapy won’t “work.” I believe there are times that lying to a therapist can be beneficial, and an essential part of the process towards a relationship in which lying isn’t necessary.

I: To Control the Pace of Therapy

Therapy can be scary, right? We’re entering this fiduciary relationship where we pay another person to talk about the stuff we generally don’t talk about. Sometimes, we’re not ready to “go there.” I’ve had patients in later stages of therapy talk about how they minimized certain stories, left others out, or intentionally altered details because they knew I’d ask about something they weren’t ready to talk about yet.

The key word here is yet—it’s OK for a patient to set the pace of therapy, to decide that she’s not comfortable disclosing something just quite yet, or that he’d rather work on something a bit more surface for a while. I believe in human autonomy—within reason. I have a stuffed elephant in my office to remind patients that sometimes, it’s beneficial to talk about the elephant in the room, but it’s also OK to say, “I’m not quite comfortable with that yet.” Sometimes, lying is a learned behavior. The patient doesn’t trust that the therapist will respect the statement “I’m not ready to go there yet,” so they lie instead. Do I prefer being told honestly—“I’m just not ready”? Sure. But that type of disclosure typically happens after a great deal of trust is established.

II: Instrumental or Pragmatic Lies

Sometimes, people lie to therapists to achieve specific goals. This might be something like misrepresenting finances to qualify for a lower rate or minimizing symptoms because they don’t want to be admitted to an inpatient unit. In some ways, these lies are barometers of just how surface a relationship is. While I’m not sure these are beneficial lies, to some extent they’re the artifact of our broken health care and managed care systems.

III: Trying on a Success Identity

Sometimes, a patient lies to try out a part of the self that hasn’t quite manifested. For example, exaggerating a confrontation with a boss that really wasn’t quite as assertive and well-managed as the patient makes it sound. This can be an essential part of becoming that assertive person. In this case, the lie helps the patient clarify where they’d really like to be. In my experience, when therapy is going well, patients tend to “own up” to success identity lies, and they talk about how enjoyable the fantasy was, and how the therapist can help them get there. This type of fantasizing can precede a true breakthrough. It can be the first step toward using those skills in the real world.

IV: To Magnify Voice

I tend to see a lot of post-traumatic survivors and thrivers. These are people who have experienced trauma in their lives—bullying, abuse, neglect, abusive family dynamics—and other forms of trauma that are not so clear-cut. Unlike “big T” traumas—the type where the abuser/victim dynamic is clear (for example, being the victim of an assault or a robbery), family trauma can often be ambiguous and confusing. The type of relational aggression that girls tend to engage in—surface “niceness” covering up problematic aggression, exclusion, and general meanness—can be confusing. A parent who is dealing with personality disorders, like narcissism or borderline traits, can gaslight a child, making the abuse ambiguous and difficult to express verbally.

The temptation to magnify an abusive encounter so as not to have it dismissed is understandable. People who have survived bullying or abusive family dynamics are used to having aggressive behavior explained away—“You and Sarah are friends,” “What did you do to make your father so mad?”, “Don’t be so sensitive, sheesh! You’re such a drama queen.” When a patient works up the courage to finally tell her therapist about an incident, only to have the therapist join the pantheon of minimizers or gaslighters, can be a terrifying prospect. So, if editing a story—turning a sneer into a shout, an implied slight into a spoken insult, or a scary look into a physical altercation—will ensure that doesn’t happen, it’s understandable that the patient might do this.

Of course, this can be ultimately counterproductive, because the validation the therapist will provide won’t feel as authentic or satisfying. But the temptation to lie to magnify voice is understandable. Sometimes, having that conversation—about being tempted to lie or exaggerate so that the therapist will understand the dynamic—is what moves therapy forward and helps clarify the ambiguous underlying dynamics. Being validated and understood after disclosing this type of ambiguous dynamic moves healing forward in the way little else can.

V: To Provide Insight

In later stages of therapy, once trust has been established and therapy is going well, reflecting on early lies may provide a patient with insight. A patient may say something like, “Come to think of it, I never told you about that. Back then, I thought you might judge me, so I never talked about it.” When I asked about lying to therapists on a recent Instagram Live I did, a participant told the following story:

I was in therapy, and I really liked my therapist. I thought he was wise and understanding. He helped me with a lot of stuff, and to a large extent, I was successfully able to go away to college despite a history of social anxiety due to my work with him. When I was in a Psych class, I had to take a questionnaire about some psychological symptoms people experience. There was one thing I used to do—it had to do with some hang-ups I have about eating—and I was about to check off “No,” when I realized I always lie about this. Even Dr. B—who I liked and trusted so much—never heard about this part of me. That’s what made me realize I need to get some therapy for this. If I couldn’t talk about this with Dr. B—that meant it was a real problem, and it was time to stop lying to myself about it.

To a certain extent, we’re always lying to ourselves, so that means we’re always lying to our therapists. We come into therapy certain that another person is “the problem,” that a situation is “the problem,” or that the world is out to get us in some way. We’d like to believe certain behaviors are “no big deal” and “don’t really affect me,” but deep down, we know that’s not quite true. Therapy helps us see the pattern behind those problems, the way we can change to change our situations, and the blind spots we may have. It doesn’t matter if we’re engaging in psychodynamic psychotherapy or any of the cognitive disciplines—at the heart of psychotherapy is seeing the world more fully as it is. Honestly, lying to a therapist might be part of that journey.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.