Politics

Why Do Some Men Support Aggressive Policies and Politicians?

Does "precarious manhood" contribute to aggressive politics?

Posted July 17, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Research suggests that Donald Trump got more support in areas where indicators of precarious masculinity were more prevalent in Google searches.

- Our research did not show the same patterns in the 2012 or 2008 elections.

- The findings are only correlational, but suggest that "precarious manhood" ideas may predict support for traditionally masculine politicians.

By Eric Knowles, Ph.D., and Sarah DiMuccio, Ph.D.

The election of Donald Trump in 2016—and his continued popularity throughout his presidency and in the 2020 election—has been a topic of widespread interest to many for the past five years. One of the characteristics that has set Trump apart from other presidential candidates and politicians is how he tethered his political image to traditional notions of masculinity. Trump’s rhetoric and behavior, in many ways, exuded the quality of machismo. His behavior also seemed to have struck a chord with many male voters in the 2018 and 2020 elections. (See, for example, the “Donald Trump: Finally Someone With Balls” T-shirts common at Trump rallies.)

Our research, however, suggests that Trump was not necessarily attracting male supporters who are as confidently masculine as the former president presented himself to be. Rather, our findings suggest that Trump appeared to appeal more to men who may be insecure about their manhood. This is called the “precarious manhood thesis.” In fact, our research suggests that men who feel insecure about their masculinity were more likely to vote for Trump in 2016 and more likely to vote for Republicans in 2018.

What is “Precarious Manhood”?

Research shows that many men feel pressure to look and behave in stereotypically masculine ways—or risk losing their status as “real men.” Masculine expectations are socialized from early childhood and can motivate men to embrace traditional male behaviors while avoiding even the hint of femininity. This unforgiving standard of maleness makes some men worry that they’re falling short. These men are said to experience “precarious manhood.” This concept has been frequently mentioned in the media under the largely synonymous term “fragile masculinity."

The political process provides a way that precarious men can reaffirm their masculinity. By supporting tough politicians and policies, men can reassure others (and themselves) of their own manliness. For example, the sociologist Robb Willer has shown that men whose sense of masculinity was threatened increased their support for aggressive foreign policy.

We wanted to see whether precarious manhood was associated with how Americans vote—specifically, whether it was associated with greater support for Trump in the 2016 general election and for Republicans in the 2018 midterm elections.

How We Measured Precarious Manhood

Measuring precarious manhood poses a challenge. We could not simply do a poll of men, who might not honestly answer questions about their insecurities. Instead, we relied on Google Trends, which measures the popularity of Google search terms. As Seth Stephens-Davidowitz has argued, people are often at their least guarded when they seek answers from the Internet. Researchers have previously used Google search patterns to estimate levels of racial prejudice in different parts of the country. We sought to do the same with precarious manhood.

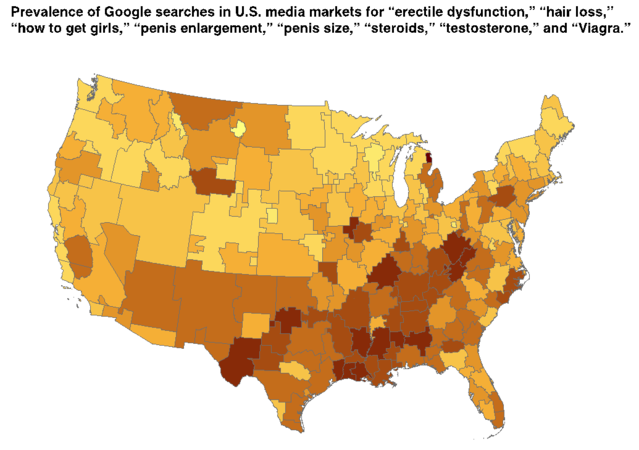

We began by selecting a set of search topics that we believed might be especially common among men concerned about living up to ideals of manhood: “erectile dysfunction,” “hair loss,” “how to get girls,” “penis enlargement,” “penis size,” “steroids,” “testosterone,” and “Viagra.”

To validate this list of topics, we asked a sample of 300 men on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform whether they ever had or ever would search for them online. We found that men scoring high on a questionnaire measuring “masculine gender-role discrepancy stress”—a concern that they aren’t as manly as their male friends—was strongly associated with interest in these search topics. Although these men were not a representative sample of American men, their responses suggest that these search terms are potentially a valid way to capture precarious manhood.

How This Measure of Precarious Manhood Was Related to Voting Behavior

We measured the popularity of these search topics in every media market in the country during the years preceding the last three presidential elections. In this map, darker colors show where these searches were most prevalent in 2016:

We found that support for Trump in the 2016 election was higher in areas that had more searches for topics like “erectile dysfunction.” Moreover, this relationship persisted after accounting for demographic attributes in media markets, such as age, education levels, and racial composition, as well as searches for topics unrelated to precarious manhood, such as “breast augmentation” and “menopause.”

In contrast, this measure of precarious manhood was not associated with support for Mitt Romney in 2012 or support for John McCain in 2008—suggesting that the correlation of precarious manhood and voting in presidential elections was distinctively stronger in 2016.

The same finding emerged in 2018. We estimated levels of precarious manhood in every U.S. congressional district based on levels in the media markets with which districts overlap. Before the election, we preregistered our expectations, including the other factors that we would account for.

In the 394 House elections pitting a Republican candidate against a Democratic candidate, support for the Republican candidate was higher in districts that, based on the Google search data we analyzed, had higher levels of precarious manhood. However, there was no significant relationship between this measure of precarious manhood and voting in the 2014 or 2016 congressional elections. This suggests that precarious manhood has now become a stronger predictor of voting behavior.

Notably, precarious manhood was unrelated to support for female candidates in the 2018 elections, once we accounted for the fact that female candidates are more likely to be Democrats than Republicans. It, therefore, appears that precarious manhood doesn’t reduce support for female candidates, but rather increases support for Republican candidates of any gender.

What's the Takeaway?

Our data suggest that precarious manhood is a critical feature of our current politics. Nonetheless, points of caution are in order.

Importantly, the research reported here is correlational. We can’t be entirely sure that precarious manhood as we measured it is causing people to vote in a certain way. However, given that experimental work has identified a causal connection between masculinity concerns and political beliefs, we think that the correlations we’ve identified are important.

Eric Knowles is a social psychologist at New York University who studies the influence of group identities on political attitudes and behavior. Sarah DiMuccio is a recent Ph.D. graduate from the psychology department at New York University whose research examines the role of masculinity in social and political behavior.

References

A version of this post also appears on the Monkey Cage.