Creativity

Hercules Shoes: Disability, Visibility, Creativity, and Joy

Meg was not expected to breathe, but she did. Her life story will inspire you.

Posted August 22, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- In a debut memoir, Meg Moore narrates her childhood experiences growing up with a physical disability.

- Moore teaches others living with disabilities and adverse circumstances that they can persevere and thrive.

- Children who are considered imperfect are often omitted, deleted, or written out of public scripts.

- A nurturing, accepting, and joyful environment can prevent differences from becoming disasters .

How is your birth story going to inform your life story? What would your life be like if, from the first moment of it, you were not expected to live? What if no one thought you could take a breath on your own?

"The Bold, The Brave, and The Breathless: Reveling in Childhood’s Splendiferous Glories While Facing Disability and Loss" enlivened my summer: Margaret Anne Mary Moore’s lyrical, energetic, humorous, unflinchingly deeply personal stories take us through real-life challenges faced by a young woman whose life is informed by her disability but not erased or impoverished by it.

Meg was not expected to live more than a few hours. Her life story, however, will inspire you.

The author is known as Meg by those close to her—as you will become when you read her book. You’ll hear her voice when it’s laughing, when it’s teasing, when it’s frustrated or anxious, and when it’s triumphant. Meg’s voice, when you meet her in person, as I’ve been fortunate enough to do, comes through what appears to the unsophisticated person (me) to be a magical device although it is merely one of an orchestra of technological devices over which Meg is the maestro.

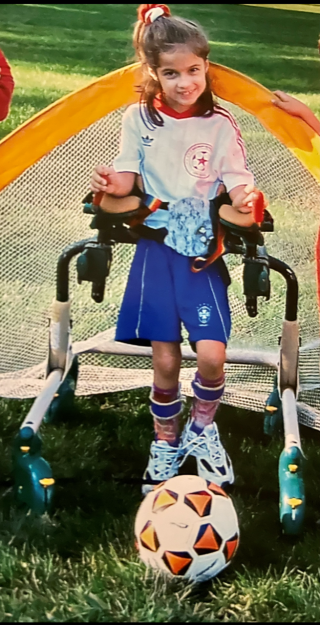

As Meg describes it, "My debut memoir narrates my childhood experiences growing up with a physical disability, cerebral palsy, relying on a wheelchair, walker, and speech device, losing my father to cancer, and being raised with two brothers by a single mother who enabled my pursuit of education, athletics, and extracurricular activities.” The impressively detailed and honest prose gives us a direct line to Meg’s experience; we go through her years with her.

Meg wrote the book, she explains, “to teach others living with disabilities or adverse circumstances that they, too, can persevere and thrive in ordinary and extraordinary endeavors."

Receiving an MFA from Fairfield University and working as an editor and marketing coordinator, Meg personifies a young woman with resolve, an unrivaled work ethic, and a passion for creativity. That would be inspiration enough, but Meg had to take a particularly circuitous route to her success. As a child, she would rely on what her brothers enviously called her “Hercules shoes”: forms of equipment that would aid her in moving. Such equipment and technologies became part of everyday life, barely worth mentioning except by way of explanation. Meg learned how to help those around her understand how her devices worked, and in so doing educated an increasingly wide and appreciative collection of friends and admirers.

But of course, in addition to those situations tailored to her unique circumstances as a child needing intensive physical care and sophisticated equipment to aid her in getting through the day, she had to deal with the usual miseries of mean kids, sneering teachers, and the heartache of ordinary childhood.

One resonant passage focuses on a selfish, petty, and unkind teacher whom Moore names, in a decidedly Dickensian manner, Miss Treet. She took a photograph of the class Meg was part of—but omitted Meg. Despite Meg’s mother, a vigilant and fierce advocate for her child, insisting that another photo be taken including Meg, Miss Treet displayed for the rest of the school year only the picture that erased Meg.

Children who are considered imperfect in some way are often omitted, deleted, or written out of a public script; many of us have had a version of this experience. But not many of us have sufficient resilience to allow us to get through it, and not everyone has a mother like Meg's.

The extraordinary caretaking and loving environment provided by Meg's indefatigable single mother, her brothers, her uncle, and other members of her extended family helped Meg become involved in a variety of school activities, including Girl Scouts, sports, school dances, and other extracurricular activities, as well as achieve top academic honors.

A fun section chronicles a trip to Disney and Meg’s experiences of going on the rides (and dealing with the crowds). All the book's passages give us a sense of Meg’s perspective on our shared humanity.

Until far too recently the disabled were erased, considered a shame to their families. “The disabled were dramatically underestimated, and therefore criminally uncultivated,” writes Jennifer Senior in "The Ones We Sent Away" in the September 2032 issue of The Atlantic. “Hidden in institutions, treated interchangeably, decanted of all humanity....Spectral figures at best, relegated to the margins of society and memory. Even their closest family members were trained to forget them.”

The article focuses on Senior's maternal aunt Adele, who was institutionalized until the age of 28 because of microcephaly. Senior explains that she never knew her aunt until recently, describing Adele as a “phantom bough” on the family tree.

I forwarded Senior’s article to Meg, suggesting that, in some ways, the depiction of Adele’s life was a dark mirror to her own shining, boisterous, and illuminating life. Meg’s writing is powerful, an essential contemporary reply in the ongoing conversation about inclusion, disability, the shared yet unique experience of otherness.