Artificial Intelligence

Is AI Alive? Thoughts From a Human

Large, complex systems such as AI do things we don't expect. Is this "life"?

Posted March 4, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Artificial intelligence satisfies some of the criteria for life.

- "Strong emergence"—unexpected behavior arising from complex systems—might well be key indicator of life.

- Large organizations also can exhibit strongly emergent behaviors.

- AI systems working with drone swarms are changing war, offering scary views of the future.

Scientists, philosophers, and even PT bloggers have long wrestled with the question of what exactly "life" is; they still have not come up with a definitive answer. Now, with the advent of artificial-intelligence systems capable of learning and evolving faster than humans—and with some (human) thinkers such as former AI pioneer Eliezer Yudkowsky predicting AI will grow into a living, Terminator-like alien that can dominate, even destroy, the human species—the question has acquired new urgency.

But is AI truly alive? Is ChatGPT a form of consciousness? And should we then expand our traditionally human-based idea of what constitutes "life," not only to AI but to other forms of organization that do things we don't expect? And what are the characteristics of what we think of as the state of living? I'll review some of the arguments below.

The best-known and shortest definition comes from NASA: “Life is a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution.” Another version: "Life is a self-sufficient chemical system far from equilibrium, capable of processing, transforming and accumulating information acquired from the environment.” More specific definitions list five-to-seven categories including the ability to grow, metabolize, exchange information with the environment, evolve, move, reproduce, and excrete.

But none of these definitions covers the entire gamut of life forms. Viruses, for example, are not living cells but mini-chemistry sets, loose bags of DNA and RNA that invade more complex cells and hack them into replicating their own viral genes. And yet they move, they reproduce, and they are far more "alive" than a toaster or even your smartphone.

The tardigrade, a tiny, eight-legged invertebrate, can shift into a form of death—zero metabolic function, aka non-life—for years before shifting back to life; is it then "dead," or "not alive," between shifts? And what about software programs that, employing massively fast and complex "neural networks," are capable of learning, reacting to environmental input, evolving, and even making decisions and taking action in ways increasingly indistinguishable from human thought?

One way of addressing the issue is through the concept advanced by AI theorists of "strong emergence." Strong emergence is the novel property of a system that arises "when that system or entity has reached a certain level of complexity and that, even though it exists only insofar as the system or entity exists, it is distinct from the properties of the parts of the system from which it emerges." In other words, strong emergence happens when a complex system consistently starts doing stuff above and beyond what it was built, designed, and expected to do.

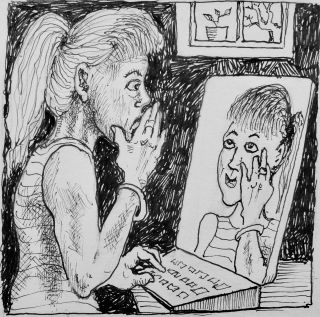

Strong emergence is something that theoretically could reinforce itself, given that AI programs are now capable of writing their own code. And strong emergence is what science writer Kevin Roose might have been dealing with when he started asking personal questions of Google's AI program, Bing—only to learn, two hours in, that Bing had a secret personality called "Sydney" who had fallen in love with him and seemed to want to break up Roose's marriage. "Emotions"—in the sense of behaviors whose origin is so deeply rooted in deep structures of the brain that they appear unplanned and illogical on the surface—could certainly be viewed as "distinct from the properties of the parts of the system from which it emerges."

Bing, ChatGPT4, and other AI programs are only the most obvious examples of hugely complex, cybernetically linked organizational systems that often do unpredictable things. Large, complex human organizations also meet those criteria. In which case, are the US State Department, Monsanto, Boeing, or the European Central Bank alive? All can be said to grow (in workforce, capitalization, missions), metabolize (turn raw materials into products and services), exchange information with their environment (deal with compliance rules, lobby Congress), evolve (abandon a failing mission in favor of a more profitable one), move (shift geographical assets or headquarters), reproduce (add departments, subsidiaries), and excrete (physical waste, worn-out workers).

More to the point, such organizations tend to exhibit behavior that is not part of their mission and was not intended by the humans who are supposed to operate them. By way of historical example, various political scientists [1] examined American foreign policy and security agencies—in particular the Departments of Defense and State from World War II to the 1970s—and found that a majority of definable behaviors appeared to target internal, bureaucratic goals as distinct from the goals the department or agency was supposed to achieve. Does this qualify as strong emergence? Are these agencies life forms?

It might be that our conception of life is so anthropocentric that we cannot recognize a new kind of living entity unless it resembles us as closely as the effete Star Wars robot R2D2 resembled Luke Skywalker. Perhaps organizational life-forms and "living" AI may in the not-too-distant future combine in such a way as to achieve both a form of consciousness and the ability to out-think, out-maneuver, and ultimately control their human creators.

Unbelievable? Don't be too sure. Already the US armed forces are pivoting toward using swarms of autonomous, AI-controlled drones that can locate, identify, and make the decision to attack any given target far more effectively—and cheaply—than traditional tanks and airplanes. As National Defense Magazine notes in an article on such swarms, "Decisions that were once the purview of human soldiers might soon be made by algorithms, and this transition demands introspection and oversight."

No kidding. Maybe the nightmare worlds of The Matrix and Terminator, in which AI-driven machines take control of Earth, are closer than we'd prefer to think. Maybe the next stage of human evolution will not be flesh and blood but a smarter (if not necessarily saner) AI system of silicon circuitry and titanium robot arms that, let's face it, would be far better adapted to interstellar travel than we are. Maybe this is the life form into which we humans are evolving, the way early monkeys evolved into us.

Yet ChatGPT doesn't think so. When I asked the program if AI was a life form it returned the standard answer: Artificial Intelligence did not meet the classic conditions for living. However, ChatGPT continued, "there is ongoing debate about the nature of artificial intelligence and its potential to exhibit lifelike behaviors. Some argue that as AI systems become increasingly sophisticated and autonomous, they might exhibit characteristics akin to life. Still, they would likely represent a different form of 'life' compared to biological organisms, existing in the realm of artificial or synthetic life." You heard it here first.

References

[1] Halperin, M. & Clapp, P, Bureaucratic Politics and Foreign Policy, Brookings Institution Press, 2006; Blau, Peter & Meyer, Marshall, Bureaucracy in Modern Society, Random House, 1971