ADHD

Going Gluten-Free Saved My Son and Me

Personal Perspective: How a tiny protein taught me that biology drives behavior.

Posted July 11, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Celiac disease is an auto-immune disorder that often goes undiagnosed for years.

- Behavior challenges are associated with celiac disease in young kids.

- Psychological symptoms are not always recognized as signs of celiac disease.

When my son Marty was born, I assumed that if anything went wrong with the 26 billion cells in his body, the doctor would know.

I got used to good news.

Marty walked and talked early. More than anything, he was happy.

He played with his backhoe loader and excavator. He loved Thomas, Percy, and Gordon, studying their pistons and personalities. “Thomas is kind,” he said.

He discovered dinosaurs, took a deep dive, and shared his knowledge with anyone who would listen.

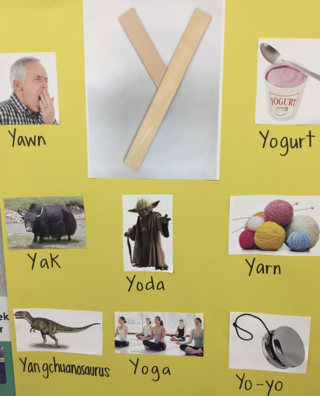

His preschool teacher told me what happened when the letter of the week was “Y.”

“Yo-yo,” one child yelled. “Yoda!” said another.

Marty raised his hand.

“Yangchuanosaurus,” he said.

The teacher spelled it with "s-h." “No!” Marty said. “It’s c-h!” Her screensaver was a picture of Marty roaring like a T-Rex.

At home, Marty was easy. He ate well. At first, it was chicken drumsticks and fried eggs. Later it was pancakes, pizza, and pasta.

Little did I know that gluten, a protein found in Marty’s favorite foods, was destroying his small intestine and wreaking havoc on his brain.

It took five years to figure this out while Marty suffered in silence.

A hidden epidemic

I used to roll my eyes when I heard someone ask for gluten-free food. I thought celiac was a state of mind, not a dangerous disease.

Turns out I was way wrong.

Gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye, is a poison for the 1 to 2 percent of people who have celiac disease. Eating even a crumb triggers an immune reaction, causing damage that starts in the stomach and spreads, often going unnoticed for years.

“What surprises me most is how often we miss it,” Dr. Anne Lee, a nutritionist at the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, told me.

She recognized signs in her son. In school, he lay on the floor, not listening. Dr. Lee asked for a celiac test. The pediatrician pushed back.

“Humor me,” she said.

She knew that fatigue and distracted or disruptive behavior could be celiac symptoms.

A simple blood test confirmed her son’s diagnosis.

He was lucky he had a mom in the know.

Dr. Nasim Khavari, a pediatric gastroenterologist and the director of the Celiac Disease Program at Stanford Children's Health, said kids are often diagnosed late because “the symptoms are so subtle.”

When pediatricians think of celiac, they expect to see constipation, bloating, or gas, but there are a slew of psychological signs that aren’t on their radar, including increasingly common childhood conditions like ADHD and anxiety.

“We used to think that [celiac] was a purely gastro illness,” Dr. Khavari said. But research in the last decade shows it’s much more.

School struggles were symptoms no one saw.

Marty had a tough time following directions in pre-K. His teachers suggested it was poor parenting.

“Are you setting limits at home?” they asked. I scolded myself for not giving Marty more time-outs.

In elementary school, Marty’s teachers said “he could decode anything and had a knack for numbers,” but he was disorganized and distracted.

Marty complained about schoolwork. He couldn’t keep up. He said he was “sleepy,” and his brain “felt confused.”

The doctor tested for Lyme, thyroid disease, and anemia. All were negative.

We consulted a psychologist. “He can’t tolerate frustration,” she said. “Let him struggle more.”

But every day was already a battle.

As Marty’s biology betrayed him, I was oblivious.

Marty ate plate-sized pancakes each morning. The food that I thought fueled his day was destroying his body’s ability to function.

Gluten turned his immune cells into traitors. They mistook the protein for a toxin and attacked his small intestine. It surrendered and stopped absorbing vitamins and nutrients that are essential for growth, energy, and basic living.

But the damage doesn’t stop there. Doctors debate exact details, but the body’s immune response is believed to inflame the brain and cause changes in behavior.

No wonder Marty got grumpy.

Little stressors caused him big angst. Transitions were tricky. Getting to school on time, or some days at all, was a strain.

Once in class, he often opted out or got oppositional, a state of mind associated with celiac in some kids.

Kids with untreated celiac are “not absorbing the nutrients that [their] body needs,” Dr. Lee, the nutritionist, said. They “don’t have the bandwidth” to meet the demands of everyday life or participate in school.

But no one blamed biology. Instead, fingers pointed at me.

“You’re not setting clear expectations at home.”

“You give him too much control.”

“Create a morning routine chart and make him stick to it.”

I berated myself for not being a better mother and bought a laminator from Amazon. I created a quality chart with explicit steps in numbered boxes. In between work calls, I fiddled with fonts.

No matter what time we started, Marty always ran late. It didn’t matter if I screamed, sobbed, or stayed calm.

Maybe if I had used Helvetica instead of Times New Roman, Marty would have been motivated.

The only thing that changed was his mood. He hardly smiled.

Things went from bad to worse, and no one knew why.

Marty woke up every morning exhausted.

On a ski trip, he was too tired to get to the chairlift. “I’m retiring,” he said.

Back home, I feared my phone.

“Marty needs an early pickup,” his teacher called, often around noon. “He’s drained.”

I couldn’t make sense of the situation.

We consulted top doctors.

Not one asked about nutrition or considered celiac, but they all recommended complex medications or expensive therapeutic interventions.

I considered everything and tried some.

“Why is nothing working?” I asked my husband.

At night, I put a pill called Xanax in my mouth and swallowed.

Doctors diagnose in their silos.

Celiac’s signs are sneaky.

Doctors don’t expect a gut disease to present as a mood or behavior disorder.

Dr. Salvatore Alesci is the chief scientist at Beyond Celiac, an advocacy group that raises awareness.

“[Doctors] see this disease as a gastro-intestinal [disorder.] They look at stuff in the gut. They're not focusing on the rest,” Dr. Alesci said.

Fatigue, forgetfulness, difficulty concentrating, and mental confusion were among the symptoms known as "brain fog" that 90 percent of celiac patients reported in a study sponsored by Beyond Celiac.

Marty had all of those.

The final clue: development interrupted.

I thought Marty had shrunk. He had become shorter than his classmates.

“That’s weird,” I said to my husband. His height had been in the 60th percentile.

I measured him. He was down to the 15th.

I consulted Dr. Google, searching for “cancer symptoms and kids.” I spoke to Marty’s pediatrician.

“Marty stopped growing,” I said. “He’s so tired; he can’t get to school. He’s confused and cranky. Could it be cancer?”

The pediatrician requested blood work and included a celiac test when he saw Marty’s growth chart.

He called a week later. “Marty’s celiac antibodies are higher than we can measure,” he said, telling me not to let even a crumb in Marty’s mouth.

I searched our pantry for products that had poisoned my son and packed them up.

We all went gluten-free.

Feeling happy and (gluten) free.

Since February, we’ve been eating eggs, salmon, and steak. We haven’t put much in our mouths that was processed.

Marty’s life changed. He smiles and has stamina. At school, they see it too.

“Marty focused for forty minutes in science.”

“Marty said math was too easy.”

“Marty asked to stay all day.”

Dr. Khavari, the pediatric gastroenterologist, loves to see her celiac patients recover.

“One of the things that surprises me is just how great people feel on a gluten-free diet,” she said.

“It's one of my favorite diseases because you fix it” without medications with side effects.

On our first gluten-free ski trip, my boy was back.

“Let’s go, Mom!” Marty yelled as he skied passed me on a steep run. “Ski faster!”

“I’m tired, Marty,” I said.

“One more run! Then let’s swim and go to dinner.”

At a restaurant, the waiter took Marty’s order.

“May I please have the salmon, gluten-free?” Marty asked. “I have celiac.”

They chatted about gut health and feelings.

“I’ve never seen such a polite and happy kid,” the waiter whispered to me. “Whatever you are doing, keep doing it.”

“It’s not me,” I said. “My son’s biology is behaving.”

Summing It Up:

I used to believe that happiness was a choice. I placed free will on a pedestal. It exists, but in a range, when the cells in our bodies work. Marty hasn’t eaten gluten in four months. Some days are better than others, but his clothing size has gone up from small to large, and he is playing sports again.

“I feel great!” Marty said this morning.

When I see him smile, I do, too.

References