Resilience

Taking Risks and Dabbling in Danger Keeps My Son Safe

Why I won't tell my son to be careful when he plays with his pocketknife.

Posted July 22, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Exposing kids to age-appropriate discomfort, danger and distress helps them build resilience.

- Unstructured free time gives kids the chance to play and build confidence, independence and flexible-thinking skills.

- When kids take risks they learn how to bounce back from feeling fear and frustration.

When my son Marty was about 5 years old, I used to say, “Be careful!” a lot.

When Marty jumped off the stairs, I said, “Be careful when you land!” At the playground, he ran with friends through man-made obstacles (on padded ground), “Be careful, you might trip!” I yelled.

Why kids shouldn’t be careful

I flinch when I realize how overly protective I was. I’m a former war reporter and rock climber and I should know from experience that taking reasonable risks builds resilience and independence. As a parent, I know these are crucial for my son.

By limiting Marty’s exposure to danger, was I depriving him of the chance to develop competencies he needs to navigate through life’s stresses?

Dr. Camilo Ortiz, a clinical child psychologist and professor at Long Island University who works with school-age kids, says yes.

He said many parents (like me) are keeping their kids too safe. He says children need exposure to what he calls the 3D’s: discomfort, distress and danger. Without that, kids don’t learn how to recover from feeling fear and frustration. They are “vulnerable and less able to handle real-life stress” later in their lives. He said, “If I could remove one phrase from parents’ vocabulary, it would be, ‘Be careful!’”

So I gave my son a pocketknife and bit my tongue

With this in mind, I gave my nine-year-old son a pocketknife.

Marty pulled the four-inch, serrated metal blade out of its safety slot, popped it into place and said, “Mom! I’m going to make a spear!”

I immediately questioned my decision.

His left thumb was a centimeter away from a trip to the ER and I made a mental list of things that could go wrong: a cut with some blood, a lacerated finger, an unintended amputation.

I visualized the doctor holding Marty’s severed fingertip in a Ziploc bag while asking, “Who supervised this child as he played with a sharp knife?”

I fought the urge to warn Marty of the obvious danger. To supervise. To manage his experience.

But instead of telling him to be careful, I said nothing. The only sound his ears heard was his knife scraping bark from a broken-off tree branch. He was in the zone, and I didn’t dare interrupt.

“Look at my spear!” he said hours later, holding the now-smooth branch close to his heart, like a gold medal.

My mom never told me to “Be careful!” and I turned out fine

In the 1980s, when I grew up, my marching orders were to get outside. To explore. To err on the side of risk.

I had that chance each summer when I spent a few weeks with my family in rural Virginia. It was a seven-hour drive from our home in suburban New Jersey, but it felt a million miles away.

We stayed in a mobile home that we called “the cabin” on sixteen acres of undeveloped land on the banks of the Shenandoah River. Our neighbors were cows, copperheads, and mosquitos.

I didn’t wear sunscreen. I ate lots of sugary cereal. The adults responsible for my safety were mostly out of sight.

The upside of dabbling in danger

One July when I was about ten, my grandfather showed up with a rusty, mini-motorcycle. I didn’t listen to any instructions before I hopped on with my younger cousin Marci.

“Whooooooo hoooooooo!!!!” I yelled as we sped along a dirt road. I could feel freedom. The wind in my hair. An irrelevant speedometer. Marci gripped my waist as we bumped along.

We didn’t worry about the what-ifs. When one suddenly hit us, we didn’t have time for anticipatory anxiety.

“Hold on!!!” I yelled as we hit a rock and the bike jolted to a stop. Marci flipped over like Simone Biles but she didn’t stick her landing. There were no cell phones or Apple Watches. Our parents were probably drinking beers and playing hearts. They weren’t coming to get us. My heart raced as Marci’s eyes filled with tears.

“Can you walk?” I asked her. She nodded yes.

Marci limped as I pushed the bike back.

When we got to the cabin, we felt anything but crushed. We did it. We survived. Our chests puffed with confidence. We couldn’t wait to get back on the bike for our next adventure.

Taking risks builds resilience

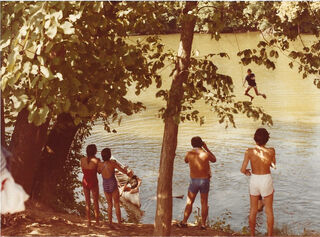

Each summer, we did something every day that scared us. The highlight was the rope swing. A frayed rope attached to a tree branch that hung over the Shenandoah River.

When I stood on the steep river bank holding that rope, I fought fear. On the count of ten, I forced myself to swing out into the unknown and drop into the river.

My mom never worried about worst-case scenarios.

The tree branch could have broken. The rope could have snapped. I could have hit my head on the rocks. In the river, I could have been bitten by a water snake.

Fortunately, not only did I survive, but when I came up for air, I emerged bionic. I was stronger. Better. Braver.

According to Dr. Peter Gray, an evolutionary child psychologist at Boston College, without the risk of some physical injury, I wouldn’t have earned the payoff—resilience and self-reliance.

Dr. Gray told me, “The whole purpose of childhood is to become increasingly independent.” He said that when kids take risks, they learn how to adapt to changing situations. They become resourceful, flexible thinkers as adults.

The value of old-school, unstructured summers

When I was 16, the Shenandoah River flooded the valley and my family’s “cabin” was destroyed. My magical summers in the Blue Ridge Mountains were over.

In the 35 years since, I’ve confronted some real-life stressors. A called-off wedding. Years later, a painful divorce. Roadside bombs in Baghdad and impossible work deadlines.

Finally, I found true love and, at 43, I held my newborn son close to my chest as I inhaled pure joy and prayed to God to keep him safe from harm.

Somewhere along the path of motherhood, I started to think that protecting Marty meant limiting his exposure to those 3D’s (distress, discomfort, and danger). I forgot what my summers in Virginia taught me. That stepping into the unknown and being uncomfortable is a child’s sweet spot. That magic happens when kids venture out without their parents’ help or supervision.

Marty gets his chance

Earlier this year, my mom decided she wanted to return to Shenandoah to celebrate her 80th birthday in July. "I want to see it one last time,” she told me.

I thought of all of the things that could go wrong: tick bites, poison ivy, heatstroke, third-degree burns, snake attacks, exhaustion, s’more poisoning.

“I think it’s a great idea,” I told my husband, who agreed, despite a preference for hotels with strong air-conditioning and high thread-count sheets.

After a seven-hour journey from our home in Long Island, we pulled onto our property. Marty jumped out of our rented RV and sprinted to the river’s edge, alone. I saw a glimpse of him wading through the Shenandoah water, oblivious to any potential dangers. What if he tripped? What if the local medical clinic was 20 miles away? What if it didn’t treat children with head injuries?

I didn’t say a word as I watched him go further and further into the river. Carefree. Happy. Confident.

What’s the worst? He gets scared and has to figure out how to make it back to the rocky beach on his own? Actually, that’s ideal.

Sum it up

Unscheduled, free time away from supervising adults is critical for child development says Lenore Skenazy, who runs Let Grow, a non-profit focused on childhood freedom and the author of Free-range Kids. According to Skenazy, when kids roam freely, they develop the confidence they will need to become self-reliant adults. When parents hover, she said children feel that “somebody else is in charge” of their life and they get the message they can’t handle life’s challenges.

3 tips for giving kids the chance to cultivate courage

1) Find an “adventure playground” or make your own

Forget swing sets, padded ground, and toddler areas. The Yard (think junkyard) on Governor’s Island, just south of Manhattan, is a 50,000-square foot “adventure playground” where old tires, broken pieces of wood, and other materials for building and destroying abound. Parents are not allowed inside. Trained supervisors watch over the kids, ages 6 to 18. Kids make the rules and figure out their own ways to have fun. Parents can create their own junkyard with household materials and age-appropriate, limited adult supervision.

2) Build a bravery practice

As I wrote in this earlier blog, psychologists say that kids can overcome their fears if they are exposed to what scares them, one small step at a time. Break the process down into manageable steps so your child can feel successful. Dr. Joe McGuire, a child psychologist at Johns Hopkins, says that when kids face their fears, they build a tolerance to distress. “We know that we are making changes in people’s brains by teaching these types of skills," he said.

3) Don’t overschedule your kids

Parents can do more harm than good when they schedule too many after-school classes, tutors, and organized activities for young, school-age kids. Dr. Ellen O’Donnell a clinical child psychologist who teaches at Harvard Medical School said many parents have “fallen into this overscheduled setup for kids that that hasn't given them room to practice dealing with uncertainty.” According to Dr. O'Donnell, tolerating uncertainty helps kids develop flexible thinking and resilience.