Play

All Work and No Play in Kindergarten

How intense school demands and parental pressure are crushing our kids.

Posted May 27, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Kindergarten classrooms are becoming increasingly academic. And anxiety is rising among young kids.

- Young learners are asked to meet demands that, for some, outstrip their abilities.

- Free play gives kids the chance to develop independence, flexible-thinking, and resilience; all are needed to manage stress.

I have a secret to share.

I keep my nine-year-old son home from school every Monday to play outside and take karate.

Marty’s wonderful teacher supports his weekly mental health day. I need one too.

For a while I thought it was just me, stressed out over the need to constantly “keep up.” I live on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, an area with affluence, top-performing schools, sky-high academic demands and intense parental pressure.

As a former war reporter, going out on patrol with U.S. forces in Iraq or Afghanistan is nothing compared to the stress of raising a child here! But a mom in Portland, Maine and another in Colorado Springs said they feel the same way. I wonder how many of us are out there.

What’s the rush?

When I think about my son’s school experience from nursery school to third grade, I feel breathless.

In pre-K, there was “writer’s workshop.” My little, four-year-old guy could hardly hold a pencil.

In kindergarten, Marty learned to read, write sentences and do simple math.

In first grade, he wrote a non-fiction book on eagles that actually included the word accipiter (Yes, I had to look it up).

In second grade the teachers said Marty was behind in writing. We hired a tutor. It helped. Kind of.

I didn’t get why he didn’t pick up how to write. I write. What’s wrong with him?

It turns out, there was something wrong with me. I’m not the only one making this mistake.

Are kids really behind in kindergarten?

When Giovanna’s daughter “Avery” started kindergarten last September in a private school in Portland Maine, the five-year-old didn’t read. Giovanna bought early-reading books and tried to nudge her along.

“Do you want to read this book?” she asked. “No,” Avery said. Giovanna got flash cards and became her daughter’s tutor because, “I felt like my kid was behind.”

Daniel Friedrich, Associate Professor of Curriculum at Columbia University’s Teachers College, says “no kid is behind in kindergarten.” The problem isn’t the kids. The curriculum changed.

No Child Left Behind, the 2001 landmark education act that tied federal funding to test scores, changed the classroom experience. Test results became the measurement of a school’s success.

Common Core, an education initiative introduced in 2010, set academic standards that outline what a student should know each year. (Forty-one states adhere.)

In Dr. Friedrich’s opinion, benchmarks are a great idea. But in reality, kids mature differently.

Friedrich says, prepping kids for the test has become the focus and kindergarten got serious.

Kindergarten is the new first grade and some kids aren’t ready

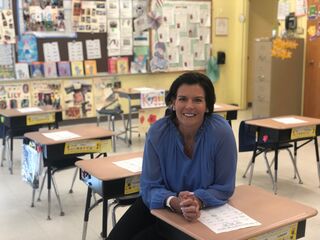

“Kindergarten is the new first grade, and I can say that because I was a first-grade teacher,” said Michelle Brown. She’s been teaching kindergarten for the last 10 years at Consolidated Elementary School in New Fairfield, Connecticut.

Kindergarten classrooms across the country have changed. Researchers of this 2016 paper concluded that “kindergarten today is characterized by a heightened focus on academic skills and a reduction in opportunities for play.”

In 2010, Ms. Brown’s students spent 1 hour and 40 minutes learning academics and over 2 hours playing. In 2021, there are 4 hours of academics. Recess is the only unstructured playtime (25 minutes).

In the past, Ms. Brown says kids in her class “had time to collaborate, to problem-solve.” Today, her class is packed with word work, reading, writing and math lessons.

“The expectations are so much higher.” She said. And many kids are not ready.

Kindergarten was a “shock”

Heather, a mom in Colorado was shocked and “overwhelmed” when her daughter “Liza” started kindergarten in Canyon City

The five-year-old struggled from the get-go with sight words and math.

Liza didn’t go to a pre-school that taught early academics. “We let her down. We didn't prepare her.” Heather said.

Because of COVID, the family moved three times and ended up in Colorado Springs where Liza, now in 1st grade, struggles with an hour of homework each night. She has math and spelling worksheets and prep for a quiz every Friday.

I remember my own son’s kindergarten experience. He was so fatigued in the afternoons that I picked him up early for two months.

“Is he keeping up with reading?” I asked his teacher. Some of the kids went to Kumon, a local academic “enrichment” center. “Should I send him?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “Kumon doesn’t teach what Marty needs.” She wanted him to play more.

But I couldn’t escape the feeling that Marty should do more, know more.

On your marks. Get set. Go!

Peter Gray, an evolutionary child psychologist at Boston College who focuses on the importance of play, thinks teaching academics in kindergarten is “absolutely crazy.” He thinks it’s nuts to “measure education” and he says too many people think education is “a race.”

Many moms in my neighborhood are in it to win it.

Some drop their kids off at P.S. 6, a local, highly-regarded public elementary school, and look so casual in yoga pants and sneakers.

But there is nothing laid-back about their expectations.

Two moms talked about getting reading help for their kindergarteners.

“Did the teachers say there was a problem?” I asked.

“No.” The moms wanted their kids to "build confidence" and "keep up."

“Why not encourage that desire to open up the doors to reading?” one of them said. After all, the school is teaching reading, so shouldn’t kids master the skill?

Pressure to excel

School psychologist Rebecca Comizio works at a New Canaan Country School, a private school in suburban Connecticut for kids ages 3 to grade 9. She sees many sources of pressure around achievement and stressed out kids. She said hiring tutors for children who are grade level is “a terrible message to send. Kids get the sense they aren’t capable or doing enough."

“We set them up to be very anxious,” she said.

Dr. Suniya Luthar’s 2004 study, The High Price of Affluence, found that teens attending top-performing schools were at risk for mental health disorders like anxiety, due to excessive pressure to excel.

Does this pressure start in kindergarten?

Kindergarten teacher Michelle Brown said that parents “want to know what the standards and benchmarks are, so their child can meet and exceed all of them.”

I’m tired just thinking about it.

One mom with kids at one of the most competitive private schools on the Upper East Side of Manhattan said, “The kids are a mess.”

“They worry. These very bright kids feel they are not enough.” She told me her son “felt this in kindergarten” because he didn’t read right away and “felt badly about it.”

Our kids are crying out for help and we aren’t listening

Rachel Henes, a social worker and consultant who works with kids and administrators in New York City’s independent schools says, “We’ve lost our way.”

“How do you know?” I asked.

“Kid after kid talks about how stressed they are.”

Michelle Brown says the shift toward academics in her classroom does more harm than good. “We've never had more anxiety than we have now.” She’s seen an increasing number of kids in her class rocking. “They're tapping. There is more explosive behavior. I'm seeing a lot of hair twirling, and biting their nails.”

Dr. Rachel Busman, the Director of the Anxiety Disorders Center at Child Mind Institute, treats school-age kids with anxiety and describes an environment of pressure around achievement that “does our kids an enormous disservice.” Dr. Busman believes the pressure is coming from parents who think, “I’ve got to get my kid into Harvard.”

I’m stressed out reading my own story. It makes me want to pack up, grab my son and run.

One solution: let them play

But maybe escaping isn’t the answer. Perhaps I can choose to parent differently.

Free play is one answer. This 2018 report by the American Academy of Pediatrics called The Power of Play found “play is not frivolous: it enhances brain structure and function and promotes executive function.”

Dr. Gray thinks nothing is more important for a child’s development than free play. “Play is how children acquire the confidence that they can meet the stresses in the world.”

Kids learn to manage their emotions and solve their own problems. They develop social skills, resilience, and empathy.

And it’s those skills, not early academic success or whether a child reads Harry Potter in first grade, that best indicate future wellness, according to this 2015 study.

A course correction

I have something else I want to share.

I was a completely unremarkable child. I didn’t read early. Writing doesn’t come easily.

I am a late bloomer in every area.

Yet, I still wanted my son to write a novella in early elementary school.

I am course-correcting now.

I just got a notice about a local day camp that is offering to tutor this summer, pulling kids from their playtime, to help them with reading and math.

I’m not sending Marty to that camp. He will play this summer. And if he is behind in his academics when school starts in September, the teacher can wait.

Sum It Up:

Kids are under increasing academic and parental pressure in elementary school. They need more time to play to develop the resilience needed to manage stress. “Through play, kids try new things.” Professor Friedrich said. They learn to fail and bounce back from adversity, without the pressure of being “graded on success.”

3 tips to help school-age children

1. Get kids the help they need before there is a crisis

Dr. Busman urges parents to get help sooner rather than later if a child appears anxious. Anxiety is highly treatable and telehealth works. Parents can connect to school mental health professionals as a first step.

2. Send kids the message: “You’ve got this.”

School psychologist Rebecca Comizio believes independence is key to building confidence and resilience. Parents should look for areas to pull back, like asking kids to make their own beds and do simple household chores.

3. Forget the future and focus on the present.

Social worker Rachel Henes believes if parents are less anxious and focus more on being present, their kids will feel better. Kids shouldn’t feel their self-worth is contingent upon an outcome. She suggests telling a child “I’m so happy to see you” at the end of the day, instead of asking about a specific school lesson or test result.