Attention

Readers Need Description to Believe a Story

Show, Don't Tell: A command keeping young writers from doing their best work.

Posted June 19, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- The saying, "Show, don't tell!" misrepresents the process of fiction-writing.

- In art composed of words, showing can't be distinguished from telling.

- Experiments indicate that action words engage people's motor systems, but the effect depends upon context.

- Writing in any field may best engage readers by combining rich descriptions with compelling scenes.

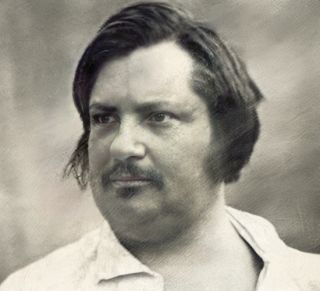

In Honoré de Balzac’s Lost Illusions, Daniel tells the young writer Lucien that Lucien has started his novel all wrong. Instead of opening with pages of dialogue among characters, Lucien should have described the characters first and shown them in action. To make readers care about who’s talking, Lucien should have given readers some passion (Balzac 227-28).

Readers vary as to what engages them. Some are pulled into stories by rich descriptions; others want immediate action. Some like getting to know characters gradually; others want to know up front who they’re dealing with. Thinking about what draws you into a story can offer insights into the way your mind works. Would you rather read a novel that starts with conversations, or one that starts with descriptions and actions?

In creative writing, no saying has been more abused than the formula, “Show, don’t tell!” People repeat it authoritatively even if they’ve never written a story in their lives. I think people cling to this idea because of a longing for certain knowledge. Craft knowledge, the wisdom of observant writers like Daniel, involves knowing how. Like the knowledge of potters and carpenters, craft knowledge entails learning creative solutions to problems by studying good and bad examples. Craft knowledge doesn’t lend itself to axiomatic rules, and it can be hard to convey in words. For people uncomfortable with uncertainty, “Show, don’t tell!” offers a convenient slogan.

In contemporary culture, “showing” suggests the presentation of direct (often visual) evidence, while “telling” implies a subjective, verbal narrative. No such distinction exists in fiction writing, where any image in a reader’s mind is evoked by words. In 2024, however, the fear of telling has become so widespread that creative writing teachers encounter student novels written almost entirely in dialogue. To avoid the dreaded “information dump,” students try to forgo description altogether, compromising their creative work.

Years ago, I was teaching George Eliot’s Middlemarch, a Victorian novel in which a wise narrator weighs the morality of the characters’ actions. Fed up with the narrator, a group of creative writing students started chanting, “Show, don’t tell!” As I stood there demoralized, wondering how to respond, two students came to Eliot’s defense. “Is it showing or telling,” asked one, “if you take a reader into a character’s consciousness?”

In art created with words, showing and telling can’t be distinguished. In a memorable demonstration, literary scholar Wayne C. Booth tried to purge all the telling from some stories by Bocaccio and Flaubert, removing every trace of an authorial voice (Booth 3-20). When Booth finished, there was nothing left. Whether or not a narrator addresses readers, a story composed of carefully chosen words will involve “instructions” to readers and will reflect the writer’s mind (Scarry 244). The question is how to balance descriptions, reflections, confrontations, and dialogue so that many different readers will care about the characters.

For some readers, a story stands or collapses based on its ability to evoke a setting. One respected writer told me and my colleagues that if a story didn’t give her a sense of place in the first five pages, she would stop reading. Admittedly, some readers skip descriptive paragraphs, but others feel that the descriptions are the story.

When I conducted interviews for Rethinking Thought, a study of how thinking varies among individuals, photographer Barbara Zettel told me that curiosity drives her to read. She likes to imagine, with all her senses, living in a place where she’s never been (Otis). Neuroscientist Hugh Wilson told me that bad writing annoys him because the writer’s use of language hinders his ability to visualize (Otis). Readers’ responses depend on the writer’s skill as well as the variations among their minds.

Cognitive literary scholar Anežka Kuzmičová has analyzed techniques writers use to make readers feel “present” in a story. She has noticed that writers often describe a place visually, then show characters interacting with their environment, especially through touch. This sequence seems to pull many readers into stories (Kuzmičová 40).

In studying how words help readers imagine bodily experiences, Kuzmičová draws on the research of cognitive psychologist Rolf A. Zwaan and his colleagues. In behavioral experiments, Zwaan’s group has demonstrated that words, phrases, and brief narratives read by participants activate their motor systems in specific ways (Zwaan & Taylor 1). For example, participants asked to rotate a knob to indicate whether a sentence was plausible or nonsensical performed faster if the sentence described a manual rotation (such as setting a washing machine) in the same direction in which they turned the knob (Zwaan & Taylor 4).

In more recent work, Zwaan has urged psychologists who study how language engages peoples’ motor systems to take context into account (Zwaan 230). One can’t conclude from a neuroimaging study of motor responses to single words that many people’s motor systems will respond to sentences or narratives with the same activation patterns (Zwaan 231). In the context of fiction reading, future studies may yield valuable results by comparing readers’ responses to information about characters “told” in descriptions or “shown” in dialogues.

To keep a broad spectrum of readers engaged, a writer must choose when to describe characters’ responses to their surroundings and when to reveal them through speech and action. In an extended metaphor, fiction writer Hanna Pylväinen has compared pacing in fiction to tempi in music (Pylväinen). At times, a piece needs to move at a walking pace (andante); at others, it can rush along at allegro. Like most musical pieces, a good story will vary its tempi and dynamics to keep from boring its readers.

Although some readers experience exposition as slow, story-time often speeds up in summaries and decelerates in scenes. When planning a story, a writer intuits what to present “in-scene” and what to convey faster, through exposition. In the "show, don't tell" formula, in-scene andante writing would be associated with showing; and expository allegro writing, with telling. Pylväinen has noticed that beginners tend to overuse andante, creating scenes to accomplish what single, well-written paragraphs could do. Deciding which confrontations readers should experience in real time and which should be quickly summarized goes to the heart of the writing process.

The need to balance description with action matters for writing far beyond fiction. Recognizing the interdependence of telling and showing, and offering description while maintaining momentum, are essential to any kind of narrative where persuasion depends on helping readers imagine an unfamiliar viewpoint. Whether the subject is medicine, politics, or marketing, an adept interweaving of evocative description, engaging exposition, and dramatic action stands the best chance to draw attention and win sympathy.

References

Booth, W. C. (1983). The Rhetoric of Fiction. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

de Balzac, H. (1974). Illusions perdues. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

Kuzmičová, A. (2012). “Presence in the Reading of Literary Narrative: A Case for Motor Enactment.” Semiotica 189, pp. 23-48.

Otis, L. (2015). Rethinking Thought: Inside the Minds of Creative Scientists and Artists. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pylväinen, H. (2017). “Tempo and Time Signature: Playing with Pacing in Fiction.” Lecture. Warren Wilson MFA Program July Residency.

Scarry, E. (1999). Dreaming by the Book. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux.

Zwaan, R A. (2014). “Embodiment and Language Comprehension: Reframing the Discussion.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 18, no. 5, pp. 229-233.

Zwaan, R. A., & Taylor, L. J. (2006). “Seeing, Acting, Understanding: Motor Resonance in Language Comprehension.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 135, no. 1, pp. 1-11.