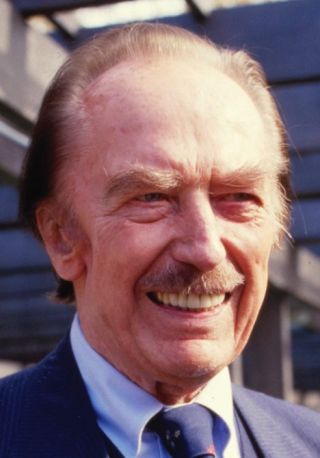

President Donald Trump

Finding Empathy Without Sympathy for Donald Trump

Clinical viewpoints illuminate the biography of historical figures.

Posted June 19, 2024 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Psychological theories bolster biographies.

- Childhood trauma and neglect can redound throughout a lifetime.

- Empathy does not entail sympathy.

Historians have sometimes been scoffed at as mere list-makers and fact-stackers, compulsive, nearsighted antiquarians. But as ambitious scholars venture to survey vast landscapes, they avidly recruit nearby disciplines: neuroscience for deep human history, genetics and linguistics for population movements, geography for the struggles over resources and terrain, biology for disease resistance and plagues, economics for the means of production and commerce and trade, technology for warfare, transportation, and discovery. And so on.

Whatever the pursuit, and however stratospheric the overview, historians also never escape chronology and detail that brings them back down to earth. Nor do they dodge biography. Knowing how a life unfolds often explains why individuals’ lives followed particular courses.

Historians and biographers have profitably mined theories of personal psychology that illuminated the way their subjects thought and felt and how they saw themselves at crucial and consequential turning points.

Psychology as a Feature of Biography

And so psychological biographies of pivotal, world-historical figures such as Augustine of Hippo and Martin Luther, Vincent Van Gogh and Mohandas Gandhi, Henry Ford and Adolf Hitler show how the sorely beset individual, for the inspirationally better or for the catastrophically worse, has changed life for the rest of us.

Sources and Subjects

In the case of United States presidents, those colorful, powerful, often inspiring, and sometimes tormented souls, biographers find that psychological theory helps them mine rich veins of explanation.

In this connection the writings, contemporary reports, and recollections of significant and complicated personalities of past presidents such as Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Richard Nixon have attracted inspired writers whose searching biographies drew from current psychological and clinical theories.

As their subjects worked through personal challenges and torments, these biographers note, their subjects changed the course of history.

The Devil Is in the Details

Presidents occasionally write and talk in revealing ways, and, when they do, historians and psychiatrists pay close attention. There they find their best material.

With an eye on the present and a consideration for the future, presidents usually weigh their words carefully, however. Our most recent past president, though, is singular among his predecessors in that he cannot stop talking revealingly. Naturally, historians, biographers, and psychiatrists have turned a cold eye toward this torrent of self-revelation. As Psychology Today has summarized, “President Trump has defiantly flipped the presidential script, making chaos and deliberate combativeness the new normal … manifest in hostile briefings, high rates of staff turnover, and cultural exchanges that appear aimed at dividing the nation.”

The Ghosts of Mal-Attunement

Condemnation or approbation belongs to politics and political campaigns;. In this case especially, let’s keep that top of mind.

But diagnosis belongs to psychiatrists and clinicians once they become biographers who trace the life histories of their subjects. Mary Trump, the ex-president’s niece, herself a clinical psychologist and a close, personal observer, has written a psychobiography of her uncle, Too Much, and Never Enough: How my Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man (2020). Personal anecdotes reveal her uncle’s odd character and strange behavior; therapeutic discipline and careful clinical observations help her and others understand him.

Alongside her book-length best-seller is a brief article by veteran psychotherapist Jeffrey B. Rubin that appeared in a recent issue of the psychohistorical journal Clio’s Psyche, “How Donald Trump’s Childhood Warped his Personality and Threatens American Democracy.”

Empathy Without Sympathy: Explaining Hostile Behavior

To explain Trump’s hostile and often bizarre behavior, Rubin draws on a staple of good psychotherapy, namely empathy, which he describes as the “steadfast effort to understand” even this most unsympathetic character.

Rubin observes how throughout his life Trump has been haunted by “the emotional ghosts of his past”—those of a dour, “harsh,” “perfectionistic” father, and a withdrawn, “un-nurturing” mother. Both parents were cold, distant, and “mal-attuned” to nurture children.

For the father, Fred Trump Sr., Rubin reserves other adjectives: “mendacious,” “cruel,” “racist-leaning,” and “domineering;” in sum, a “high-functioning sociopath” who “starved” his son Donald of “basic, life-affirming emotional nourishment.” Not incidentally, Fred Trump delivered a strangely mixed message to his maltreated young son, “You are a killer,” the father routinely said, “you are a king.”

From Troubled Teen to “Screwed Up” Adult

Thus, Donald became an ungovernable, bullying kid. Unsurprisingly, the parents farmed him out to a military academy. The long-suffering mother declared herself relieved. But away from home the young Donald felt even more abandoned, humiliated, and punished, feelings he has never ceased striving to overcome.

For all but the luckiest children of such neglectful and hurtful parents, a lifetime of unhappy relationships and an “absence of moral responsibility” often ensues. Donald Trump himself credited the source of his disruption in his as-told-to book, Think Big and Kick Ass in Business and Life (2007): “That’s why I’m so screwed up,” he testified, “I had a father that pushed me pretty hard.”

Cutting the long biography short, we now know that the troubled, brittle, needy kid grew up to become a convicted felon, an accused insurrectionist, and an adjudicated rapist.

A Niece’s Diagnosis

Mary Trump’s biography is also a case history. In it she has noted that her uncle meets “all nine criteria” identifying a narcissistic personality disorder as listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

These include grandiosity, envy, arrogance, a surpassing sense of entitlement, a craving for admiration, and fantasies of unlimited power. (Hoping to fulfill the father’s prediction, he proclaimed himself “a king” on various occasions.) Those who pay attention to social-media tirades will see the negative traits on display nearly nightly. Personality disorders, as a rule, are thought to be incurable.

References

Mary Trump, Too Much, and Never Enough: How my Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man, (2020); Jeffrey B. Rubin, PhD, “No Wall can Keep Out what Haunts Donald Trump,” Psychology Today, (December 14, 2018); Jeffrey B. Rubin, “How Donald Trump’s Childhood Warped his Personality and Threatens American Democracy.” Clio’s Psyche (Spring, 2024).

Suzanne Lachmann, Psy.D., “Petition Declaring Trump Mentally Ill Pushes for Signers,” Psychology Today (August 17, 2017); Brandy X. Lee, Robert Jay Lifton, The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump: 37 Psychiatrists and Mental Health Experts Assess a President (2019).

Donald J. Trump, Think Big and Kick Ass in Business and Life (2007).