Freudian Psychology

Advertising as Play

Hooked on modernity

Posted May 22, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Advertising was once colorless and text-heavy, now playful ads keep consumers coming back for more.

- Public relations executives deployed Freudian psychology to sell cigarettes.

- Tobacco ads relied on emotional appeals such as women's emancipation and freedom of choice.

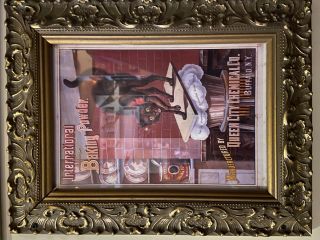

Look at the eye-catching baking powder advertisement from the mid-1880s. You’ll see a startled cat, back arched, teeth bared, tail aggressively curled against a threat, one pre-pounce foot lifted. The eyes stare holes through you. You’ve seen this cat.

The caption is the key to the joke. I’ll hold off quoting it for now.

First, a historical detour.

A Central Institution

Scholars have identified advertising as a “central institution” of our modern political economy. They say that marketing and branding means to get into our heads by initiating a conversation—that is, if transaction is conversation. The cleverest ads and most successful appeals play on our aspirations and ambitions, turning our wants into needs and, sometimes, also playing upon our fears and insecurities.

And so, the history of advertising began a century and a half ago with text-heavy and image-poor promotion of fashion and style, “reason why” descriptions of all those novel products meant to deploy and head off our fear of missing out.

Temples of Awakening Desire

Lavish new downtown department stores, temples of awakening desire, offered to an aspiring urban middle class those high-fashion items such as dresses and shoes and corsets and ties and suits for showing off. Society was also becoming more fastidious. Pharmacies sold soaps, tooth, and deodorants that minimized olfactory offense, a new worry.

Such luxury articles (eventually they became necessities) fortified a psychological and emotional trend that helped separate stylish modern consumers from the plain and less carefully groomed agrarian folk whom Thomas Jefferson, sixty years before, had called America’s “most virtuous citizens.”

With technological innovation, American life became more convenient, especially for women exhausted by domestic chores. Sellers pitched customers labor-saving appliances like vacuum cleaners and washing and sewing machines that further separated the back-breaking countryside from the more comfortable city.

And it was not just clever machinery that saved women time and effort. Chemistry also came to the rescue.

And this brings us back to the scaredy cat featured in the advertising poster.

A Visual Joke and a Puzzle

When I showed the fraidy-cat advertisement to a small group of millennials, all I got were crickets and questions. Why was the cat scared? One wiseacre said the animal “saw Scott’s face.” OK. Very funny. Flummoxed after several tries, the group finally settled on a story of smuggling white powder across the international border into Buffalo. The tabby was getting high! Literally! Nope. Sorry. This was 1885.

It’s puzzling now, but consumers in 1885 would have instantly snickered at the picture.

Our Daily Bread

So why aren’t we in on the joke? First, we need to remember that nearly all households in the 19th century, and many well into the 20th, baked their own bread daily. This task fell to women, and it took some doing.

Cooks mixed flour, water or milk, and butter or lard into a dough. They inoculated the batch with a leavening agent, usually “starter” leftover from the day before. As yeast fermented the starch, accumulating CO2 bubbles caused the dough to rise. After about four hours and a couple of kneadings, the springy dough was ready for the oven.

Better Living Through Chemistry

But during the Civil War chemists invented a shortcut—baking powder, a mix of a mild acid and a carbonate buffered with cornstarch. Adding water caused the chemical mix to fizz and the dough to rise quickly. The new process produced the “quick bread” that freed cooks from hours of toil.

The Caption Is the Punchline

So. If you stocked a really effective baking powder in your cupboard, your bread might well rise so fast that it would startle a cat slumbering on the breadboard! Hence the tagline: “Tom’s nap interrupted by International Baking Powder.” Got it now?

The millennials thought this joke took rather a lot of solving. But for the people of the day, and unlike the ponderous advertisements of the time, again, the picture was worth a thousand words.

Advertising as Play

Staid, text-heavy, late 19th-century advertising rarely featured such wit, but we’ve come to demand funny commercial messages in the 21st.

You may have forgotten the team that won last year’s Super Bowl, but you may clearly remember chuckling at a celebrity roast of Mr. Peanut, or how avocados from Mexico invaded the Garden of Eden after nudity dawned on Adam and Eve, or that time a puppy met a Clydesdale in a beer commercial.

When creative advertising copywriters and producers play around for our entertainment, they keep us coming back for more.

The Power of the Unconscious

Some more history. No figure argued more cunningly for mobilizing the power of the unconscious and the utility of group pressure than Edward Bernays, “the father of American public relations.” His impeccable Freudian pedigree included Anna Freud (mother) and Sigmund Freud (his double uncle). In the 1920s in the service of tobacco companies, Bernays deployed a feminist message to convince fashionable women to smoke. His point: To refrain from smoking was to be shackled to archaic proprieties. Cigarettes, Bernays proclaimed in 1928, were “torches of freedom.”

Manipulation, Liberation, Addiction

Three decades later a tobacco company sponsored the first animated series to air in prime time. This was not your usual kids’ cartoon. A series of commercials starred Fred and Barney taking a cigarette break. Meanwhile Wilma and Betty labored over household chores. That is until the wives asserted themselves and put the paleolithic slackers to work! Oh, those Stone Age men!

More pointedly, cigarette ads would soon portray hip, liberated women asserting their new-found self-assurance under the caption, “You’ve Come a Long Way Baby!” The mixed message be damned.

When the Joke Falls Flat

A powerfully addictive product guaranteed that smokers would keep coming back for more. The real threat? The competition might poach their customers.

Thus, one heavy-handed 18-year long advertising campaign beginning in 1963 pictured feisty brand-loyal smokers, women and men sporting black eyes, who would “rather fight than switch.”

The next year the U.S. Surgeon General reported that smokers suffered a ten-to-twentyfold increase in lung cancer.

Tobacco companies already knew the health hazards from their earlier research but plowed ahead to frame smoking as a civil right threatened by government intrusion. The defiant, fear-based strategy continues. Tobacco advertising agencies and legal teams are now battling legislation that seeks to ban menthol cigarettes that appeal to children and target minorities. These corporations would rather fight than quit.

References

Gunther Barth, "The Department Store," in City People: The Rise of Modern City Culture in Nineteenth-Century America, (Oxford University Press, 1980) pp 110–47.

Edward Bernays Propaganda (Horace Liveright, 1928); Amanda Amos and Margaretha Haglund, “From Social Taboo to “Torch of Freedom”: The Marketing of Cigarettes to Women,” Tobacco Control, Vol. 9 No. 1 (2000).

Ramses Delafontane, Historians as Expert Judicial Witnesses in Tobacco Litigation, (Springer Publishing, 2015); Kelly McGonigal, “The Sleeper Effect: Why ‘Just one Cigarette’ Spells Bad News for your Brain, your Body, and Future,” Psychology Today, (July 30, 2010); Kieth Wailoo, Pushing Cool: Big Tobacco, Racial Marketing, and the Untold Story of the Menthol Cigarette, (University of Chicago Press, 2021).