Cognition

Of Tarzan of the Apes and Monkey Bars

Playing on the jungle gym with evolution in mind.

Posted March 15, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

This is a story about the origin of “monkey bars,” the playground stalwart that we still call a “jungle gym.”

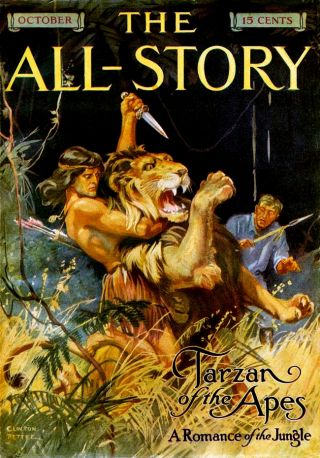

It starts not with the Princeton mathematician who assembled a bamboo climbing lattice in his back yard to tutor his children’s understanding of spatial coordinates, or with his son who grew up to be a patent attorney who designed a structure for “dimensional tag" (I’ll get to that in a bit), but with Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes, the first of many bestselling adventure thrillers in the series.

You think you know Tarzan?

If we think we know Tarzan from the Hollywood films starring the yodeling Olympic swimmer, inarticulate white savage and elephant whisperer, Johnny Weissmuller, we’d have another thing coming.

The debut Tarzan novel, published in 1914, begins on a surprisingly progressive note. Two earnest British diplomats, a husband—Lord Greystoke and his pregnant wife Lady Greystoke— embark on a delicate and humane mission to West Central Africa to help mitigate the re-enslavement of indigenous laborers by a “friendly” power (presumably ruthless Belgium). They are soon marooned on a remote shore after a mutinous crew of cutthroats (only marginally fouler than the officers they threw overboard) abandoned them.

The castaways had been left with a trunkful of tools that allowed the survivors to construct and furnish a fortified treehouse. A store of books and clothing filled in the rudiments of civilization. But this was no Gilligan’s Island.

It happened that the family shared their verdant place with a troop of murderous anthropoid apes, super gorillas with outsized intelligences and a rudimentary vocabulary, who eyed the intruders with envy and malice. Luckily the mutineers had also left the couple with firearms and ammunition, which for a time kept the tribe at bay. But with each new fatal skirmish, the rage of the troop leader deepened. As he killed Lord Greystoke in a violent rush, a stray bullet also sadly felled an infant ape clinging to the troop’s matriarch.

Impelled by grief and instinct, she snatched up the human baby. Though for many years he lagged behind his nimble primate playmates, the adoptive mother protected the future Tarzan, (“White-Skin” in ape-speech), a nascent superhero, against the leader’s revenge.

Had the novel ended there, readers would have been rewarded with a taut, short pirate misadventure. But Burroughs plowed on, now often unbearably, with stock characterization. Native peoples, naturally some of them cannibals, appeared mainly as prey and victims. Sailors and officers were uncomplicated thugs, and equally filthy. Delicate women fainted on cue. An excitable, portly Black maidservant from Baltimore mangled the language, laboriously. A blithering professor who often wandered into danger muttering “tut, tut” survived into the Disney era.

But it is in the unfolding boyhood of the human-raised-by-apes that modern readers may find some greater delight and the key to this essay.

As Tarzan matured, he came to master arboreal life; swinging from branch to branch like his playmates, he became enormously strong and agile. “He could spring twenty feet across space at the dizzy heights of the forest top and grasp with unerring precision… a limb waving wildly in the path of an approaching tornado,” Burroughs wrote. “He could drop twenty feet at a stretch from limb to limb in rapid descent to the ground, or he could gain the utmost pinnacle of the loftiest tropical giant with the ease and swiftness of a squirrel.”

Gifted also with a prodigious human intelligence, Tarzan would in time supplant his old enemy and rise to kingship. Finding the surviving books in the derelict family treehouse, Tarzan painstakingly taught himself to read (in English and French) even without the aid of phonics. With his sophistication growing, the narrator began to refer to Tarzan as “the young Englishman,” as if nationality were a biological inheritance.

Such was the reach of the self-congratulatory racialist hierarchy of the late 19th and early 20th century that placed white Europeans at the top of an evolutionary pyramid, that when new-fangled fingerprint evidence later confirmed Tarzan of the Apes as the rightful new Lord Greystoke, he literally became the noble savage, the product of a natural succession.

The “Monkey Instinct” Meets the Real World

In the text for his 1923 patent application assigned to JUNGLEGYM Inc., the designer, Ted Hinton, began conventionally, noting the scarcity of safe climbing structures in cities. Then, citing the “conspicuous advantages” of climbing as exercise, he described how lifting, stretching, and moving in three dimensions is ideally “graduated to the size and strength of the body and the tendency of the body, so exercised, to approach the proper weight and proportionate development… in the most symmetrical and beneficial manner.” Only running and swimming were of comparable value for “all the body’s muscles.”

Surely, as with all children of his day, young Ted Hinton knew of Tarzan as he knew the similar fictional man-cub, Mowgli, from the Rudyard Kipling stories written two decades before Burroughs’ work. And this helps explain why, years later, the technical language of his patent application took a turn toward play and evolutionary theory.

His structure would be doubly appropriate because, Hinton emphasized, “climbing is the natural method of locomotion which the evolutionary predecessors of the human race were designed to practice.” And then crucially, because the “monkey instinct [is] strong in all human beings,” and because it is “perhaps more clearly displayed in children,” the play apparatus that he designed would be “so proportioned and constructed that it provides a kind of forest top through which a troop of children may play in a manner somewhat similar to a troop of monkeys through the tree tops of the jungle.”

An Evolutionary Relic

We humans abandoned the treetops for the savannah some three-and-a-half million years before Hinton patented his jungle gym and delighted millions of kids. But lest you think that Hinton’s explanation or Burroughs’ imagination unnecessarily romanticizes our connection to our dim past, and if you have forgotten the pleasures of swinging, try this little experiment. Touch your pinky to your thumb with your wrist turned to face you. Three in twenty won’t see any effect, but the remaining seventeen will see a raised tendon in the middle. This sinew is connected to a forearm muscle called the palmaris longus. It is next to useless in humans. Some of us are even born without it. But for primates like monkeys and orangutans, this steely tissue helps them brachiate. Meanwhile, this relic reminds us of the era when our distant cousins swung from branch to branch.

References

Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan of the Apes, A.L. Burt (1914).

Luke D. Fannin, “The Surprisingly Scientific Roots of Monkey Bars,” Smithsonian Magazine, (March 2023); Sheila Duran, “J is for Jungle Gym,” Winnetka Historical Society Gazette, (Fall, 1997).

Marina Chapman, The Girl with no Name: The Incredible True Story of a Child Raised by Monkeys, Pegasus Books, (2021).

Cetin, A.; Genc, M.; Sevil, S.; Coban, Y. K. (2013). "Prevalence of the palmaris longus muscle and its relationship with grip and pinch strength". Hand (New York, N.Y.). 8 (2): 215–220.