Play

Why Wordle and Spelling Bee Are Not Addictions

Attraction is not addiction.

Posted March 28, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Attraction to online pattern recognition games such as Wordle and Spelling Bee is not addiction.

- Some players use gentle play as a soporific.

- Videogame disorder is an evolving diagnosis still under study.

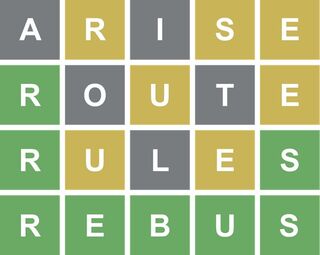

My cousin Sheila, my old friend Don, and my new friend Jane are among those who send me their ingenious solutions to each day’s Wordle puzzle, an online letter pattern-recognition game that had, according to the host newspaper, the New York Times, attracted more than 3 million players in the first six months after its introduction.

As yet, I’m not among those millions. And I don’t play Wordle for the same reasons that I purposely break the rules for a sister game, Spelling Bee, that appears daily and that I play nightly on my phone. The main reason I’m a rule-breaker? It’s that playing these word games properly requires extended concentration. And that’s an investment that I’m unwilling to make at 3:17 a.m. Following the official rules in the wee hours seems more like work than play, and while work is not strictly hostile to play, it is surely unfriendly to sleep in the middle of the night.

In fact, I play the game not out of boredom or to pass the time. Rather, for me the game play is quite the opposite: It’s my version of counting sheep.

So here’s what I mean. The game’s official rules present the player with seven different letters arranged in a honeycomb with the central letter highlighted. That letter must be used in any common word that the contestant creates. Letters can be used more than once. The game will not allow specialized words, obscure medical terms, proper names, and the like, and that seems fair enough. It won’t permit impolite words, either; and not just the seven tv-tabooed terms that George Carlin made famous. However, I understand that because it contains only two vowels and two consonants, “enema” will squeak through. Tee, hee.

Rule Breaking Inspires Rule Making

The game awards winners with terms of increasing approbation that culminate with the label “genius.” Solvers rack up extra points by finding a “pangram,” a word which uses all the letters at least once. And here’s where I become a scofflaw. I make new rules by breaking the old rules, playing the game only to find the pangram. In a few seconds or several minutes, the pangram swims to the surface in its orderly way out of the chaos below: HIALWTF resolves to “halfwit.” HIPOWLR harmonizes as “whippoorwill.” YMNOTAU turns into “autonomy.” And DRYWAZI magically transforms to “wizardry.”

Once in a maddening while — like last night in fact — the game stumps me. PADROUM immediately resolved as “ramrod,” and “mudroom,” and “paramour,” but left me one or two letters short in each case. Then I awoke this morning with “pompadour” buzzing in my head. Even in dreamland the brain does not cease from its labors.

Though the puzzle has become my nocturnal habit, I’d not go so far as to say I’m hooked on it—I could still resort to counting pronghorns or counting down from a thousand using only prime numbers. And my inclination falls far short of those enthusiasts who claim, extravagantly, to be “obsessed” with the puzzle, or even “addicted” to it. When players say that they are hooked on a game, they usually mean that they are indulging their play preference rather than feeding a compulsion. I’m against such imprecision that veers toward psychiatric diagnosis.

This issue was cast into sharpest focus when both the World Health Organization and the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders considered including “videogame disorder,” sometimes called internet gaming disorder, among its diagnoses. Though there is not yet agreement among clinicians on classifying this complex condition, it’s clear that those who cannot stop playing a game and sacrifice normal life to it—forsaking hygiene or sleep for example, or forgetting to eat, abandoning jobs and withdrawing from intimate relationships—may suffer from symptoms that more broadly resemble obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The dividends of play include pleasure, understanding, and poise. Play takes place within a magic circle, often in a demarcated space—the field, the hill, the rink, the playground. And more often games progress over a delimited time—the inning, the period, the round, the turn. Those for whom the game turns into compulsion, however, pass the unfortunate point where they are playing the game and the game ceaselessly begins to play them.

References

Scott G. Eberle, "What's Not Play: A Meditation," (2015) in James E. Johnson, Thomas S. Henricks, David Kuschner, and Scott G. Eberle, eds., The Handbook of the Study of Play, New York: Roman and Littlefield.

Deb Amlen, "The Genius of Spelling Bee," New York Times (February 14, 2022)

Joseph Kim, "The Compulsion Loop Explained," Gamasutra (March 23, 2014)