Sex

“Girls Who Wear Makeup Are Fake”

#everydaylookism stories tell us that we may never get it right.

Posted January 17, 2020 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

"Putting on your face" is something that very many of us do on a daily basis. On average, women will spend “29 minutes putting on make-up to achieve a 'natural look,'” and a third of us “never go out without make-up”. And, over a lifetime women on average spend 136 days (3276 hours) “getting ready for a night out.”

Once upon a time, respectable women didn’t wear make-up. Only "painted ladies," sex workers, wore make-up; made-up eyes, lips, and cheeks were how they advertised their trade. Gradually, make-up became OK, so much so that in the second world war lipstick was believed to be vital to morale; it was not rationed and was imported across blockades with other "necessary" supplies (Dyhouse, 2011, p.82).

Wearing make-up is now routine for many, required for work, special occasions, or to "face the day." Make-up is part of who we are such that we can raise money by not wearing it! The 2015 ‘bare-faced’ selfie campaign raised £8,000,000 in six days for cancer research. The non-made-up face is rare, and apparently make-up even makes us look more competent and professional. In a study on the perception of females’ (aged 25-50) faces with and without make-up, “ratings of competence increased significantly with makeup”, and likeability and trustworthiness also increased, although less significantly (Etcoff, Stock, Haley, Vickery & House, 2011, p.8).

But this is not always the case, and too much makeup can have the opposite effect. A 2018 study found that “regardless of the participant’s sex or ethnicity, make-up used for a social night out had a negative effect on perceptions of women’s leadership ability.” (James, Jenkins & Watkins, 2018, p.540). And in some professions wearing almost any make-up marks you as frivolous, unintelligent and not to be taken seriously. Yet while some professions require less make-up than others most of us are doing more. For example, some surveys suggest that the average women’s make-up routine in 2016 took 27 steps, compared to just eight in 2006. As most of us wear make-up, not wearing it becomes abnormal—more of a political statement than a fashion choice. What is the right amount and how can we get it right?

Some bullying statistics suggest that, no matter what we do, we can’t do it right!

While 58% of people aged 13+ think “make-up makes them feel confident” (Ditch the Label, 2017) 27% of people aged 13+ “have felt judged for wearing make-up”. (Ditch the Label, 2017)

Similarly, 75% of people aged 13+ agree that “some women would look better if they wore less make-up” (Ditch the Label, 2017). But 45% of 12-20 year olds agree that “unattractive people need to make more of an effort with their appearance.” (Ditch the Label, 2019)

This looks like an impossible circle to square, and that’s before you take into account that 63% of U.S. men agree that “women mainly wear make-up to trick people into thinking they’re more attractive.” (YouGov, 2017)

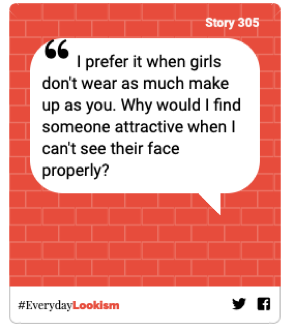

The #everydaylookism stories back this up. We can be shamed for wearing make-up:

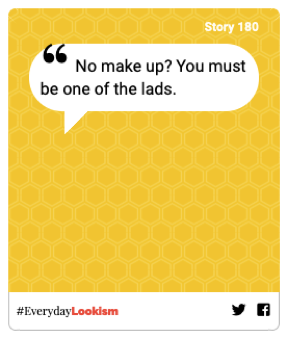

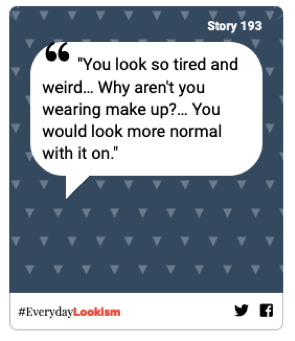

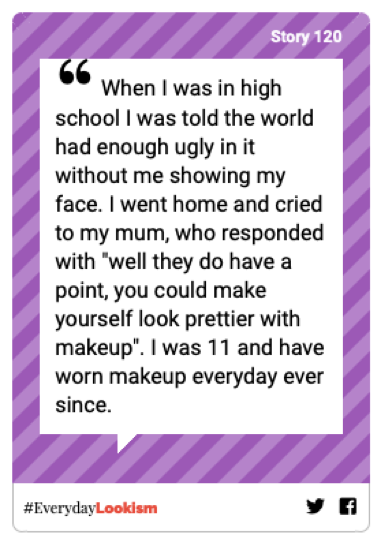

And shamed for not wearing it:

We can be shamed by those who love us:

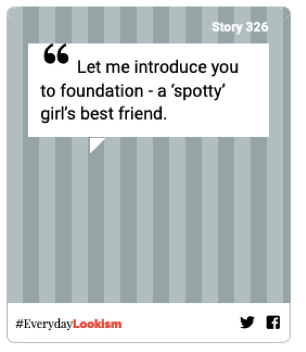

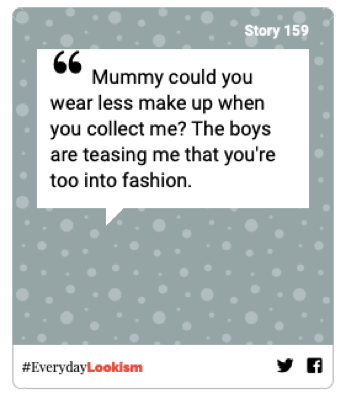

It doesn’t even have to be us wearing the make-up to be shamed:

These #everydaylookism stories show that we can’t get it right. Too much and we’re fake, too little and we haven’t made an effort or shown respect. This is going to get more difficult as make-up options change and more alternative ways of making-up the face become available. Semi-permanent make-up is becoming increasingly popular and looks like it is here to stay; permed and dyed eyelashes, high definition brows and tattooed lips are increasingly evident.

When do you decide to do your eyebrows? Those who don’t wonder at those who do. “Don’t they know they look abnormal?” a journalist recently asked me, commenting on the new trend. But no, they don’t, as they are not abnormal in their peer group. No more abnormal than the flapper who cut her hair and put on lipstick in the 1920s. Normal is a moveable feast.

There is no right amount of make-up. There may be norms for different professions—more for the air hostess than for the professor—for different events; more for a wedding than for walking the dog.

But even these norms are being unsettled as we make-up not for the real world but for the virtual world. The average 16- to 25-year-old women spends 5 and a half hours a week taking selfies, and “33% of women redo their makeup before taking photos”. If we have to be camera -eady at all times to post our perfect lives, then increasingly we have to be perfectly made-up, with make-up that is exaggerated and odd offline, even if it looks great online. If we believe the projections, the amount of time and money we spend on making-up is only going to increase. The global make-up market (for the face) was worth $31.3 billion in 2018, and it is projected rise to 36.5 billion by 2024.

The bottom line is, it’s almost impossible to navigate, which is another reason we should try to reduce the pressure, to tone down the critique. #everydaylookism seeks to end body shaming. If it becomes unacceptable to make negative comments on people’s appearance—including their make-up—then the pressure will decrease. We might still worry that we are not getting it right, but we won’t worry that we’ll be called out and shamed. Let’s change the culture, let’s call out body-shaming as people-shaming and put a stop to it. Share your make-up story at: everydaylookism.bham.ac.uk.

Heather Widdows, author of Perfect Me and professor in philosophy department at the University of Birmingham

Jessica Sutherland, research assistant and global ethics Ph.D. student at the University of Birmingham

References

Dellinger, K. & Williams, C. L., 1997. Makeup at Work: Negotiating Appearance Rules in the Workplace. Gender & Society, 11(2), pp. 151-177.

Dyhouse, C., 2011. Glamour: Women, History and Feminism. London and Mew York: Zed Books.

Etcoff, N. L. et al., 2011. Cosmetics as a Feature of the Extended Human Phenotype: Modulation of the Perception of Biologically Important Facial Signals. PLoS ONE, 6(10), pp. 1-9.

James, E. A., Jenkins, S. & Watkins, C. D., 2018. Negative Effects of Makeup Use on Perceptions of Leadership Ability Across Two Ethnicities. Perception, 47(5), pp. 540-549.