Environment

Recovering from Functional Neurological Disorders

Diagnosed with FND? Take the first steps to regain lost functioning.

Posted August 25, 2021 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

Key points

- Functional neurological disorders (FNDs) are a collection of physical symptoms that arise from disruption in how the brain and body communicate.

- Usually, the brain integrates one's awareness of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. When someone has an FND, the process is disrupted.

- Examining unhelpful connections within the brain, learning to let go of the struggle, and moving forward are key to recovery from FND.

I often see patients who—after years of unsuccessful treatment—believe that recovery from functional neurological disorder (FND) is impossible. These are the patients that I love to see. Their treatment starts with this simple realization: Despite what life seems to teach us, sometimes the lessons learned are false. Recovery from FND is possible with the right help.

Confusing Explanations

The history of functional neurological disorders (FNDs) is complicated; what we once called conversion disorders (or classified as psychogenic symptoms) have now been given a more clinical-sounding name. This is because, in recent years, healthcare has favored a biological model to explain disorders, thereby diminishing the social and psychological factors that contribute.

FNDs are described as a collection of physical symptoms that arise from a disruption in how the brain and body communicate. Which is to say, while there is nothing physically wrong with the hardware of the brain, the software is malfunctioning. In order to understand the software problem, we must look beyond the biological component; we must examine the psychological and social aspects of who we are as well.

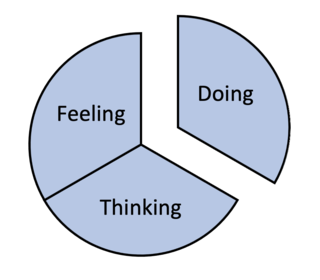

A good place to begin is to consider how our brains should function. A healthy brain creates awareness of who we are and what we are doing. We experience this as consciousness. With proper working connections, we integrate thinking, feeling, and doing from moment to moment to form self-awareness.

To explain consciousness to my patients, I use a simple drawing of a circle with three sections representing thinking, feeling, and doing. When we are functioning well, we are cognizant of what we are thinking and can identify how our emotions are related; our behavior predictably follows.

When the brain’s software is operating well, we know who we are, what we think and feel, and why we do the things we do.

In an altered state of consciousness, however, this integrative process is disrupted; we refer to this state as disassociation. In a dissociative state, our consciousness becomes disordered: our feelings, thoughts, and behavior are untethered from one another. While our observed behavior appears to be under some other kind of control, it is certainly not under our own control.

In a dissociative state, there is a profound loss of awareness. We lose connection to our feelings and thoughts and to the reasons why we act the way we do. One well-documented example: In WWII, it was not uncommon for Allied pilots preparing for massive bombing runs over Europe to completely lose their vision while waiting to take off.

Facing overwhelming psychological distress, the pilot’s brain’s protectively disconnected their thoughts, feelings, and behavior. In the days that followed, as they were encouraged to identify the thoughts and feelings related to their mission, their vision would return. With the normal integrative processes of the brain restored, their symptom disappeared.

Restoring Connections

In a recent post on functional neurological disorders, I stressed the importance of understanding how the brain makes unhelpful connections as a key component to initiate treatment. We all struggle with unhelpful thoughts and a noisy mind; by helping patients to normalize the disruptive processes that happen in the FND brain, a positive step towards change can be taken.

Physical pain, anxiety, depression, and experiencing neurological symptoms can be all-consuming. But when our attention is riveted by these distressing states, something else happens. We become much less aware of anything else going on in our lives. We are less connected to the present moment. For example, when anxiety takes hold, we are less aware of and connected to what and who are important to us and focus our attention on our internal distress.

Reconnecting with Values

From the outset of treatment, one of the steps I take patients through is a process of identifying what is important in their lives. Examining what they value reveals one source of their distress—the gap between where they are and where they want to be. In helping FND patients reconnect with their values, they are able to gain insight into their emotions and sources of stress.

Focusing on values also helps patients to dial back and see the "bigger picture" of life. When our problems become our primary focus, the connection to what is truly important is lost. A narrow focus on symptoms can lead to the feeling we are defined by our illness. But this narrow focus can shift as we zoom out and start to look at all the areas of our life that make it rich and meaningful.

Identifying Unhelpful Thoughts

Using the principles of Relational Frame Theory and the treatment approach of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), FND patients can see a way forward, even though they feel stuck.

A key process of ACT is learning how our brains make unhelpful connections. Our thoughts and feelings, along with events that happen to us, are colored by the brain’s explanations, judgments, predictions, and rules. For example, what does the word “dentist” conjure up for you? For many people, the word itself is enough to increase their blood pressure, heart rate, and muscle tension.

In FND, the existing (and unhelpful) connections need to be examined. For example, triggers in the environment (sounds, smells, events) can be linked to thoughts and feelings that will lead to the sudden onset of symptoms, such as a tremor or paralysis. It is these connections that first need to be identified and then later replaced with helpful connections. Helpful connections keep us moving toward what is important in life—as defined by our identified values—rather than keeping us stuck and consumed from what is distressing.

Moving Forward

We get stuck in life in part because we assume our thoughts and feelings are true—and because we believe that we must get rid of our distress before we can move forward. But, there is another path to follow. The culmination of several strategies and behavior modifications can radically change the software of the brain. These include learning how to let go of the struggle with our thoughts and feelings, staying connected to the present moment, and moving toward what is important to us.

As FND patients begin to let go of their struggle with unhelpful thoughts and fears of being stuck with their condition, adjunct physical and occupational therapy can then play an important role in helping to regain lost function and move forward in life. These are the keys that bring hope and freedom to people struggling with FND.