Behavioral Economics

The Chain Store Massacre

Can you rationally deter a competitor?

Posted June 18, 2024 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Predatory pricing can keep competitors out of the market.

- Rationality (backward induction) discourages predatory practices.

- Many humans are myopic, aggressive, and rewarded for it.

Life is nothing but a competition to be the criminal rather than the victim. –Bertrand Russell

The most decisive way to win at a competition is to convince any potential competitor not even to attempt a challenge. Then, the winner takes all without getting into a fight. A silverback gorilla can keep his harem and expel all challengers, at least for a while (Robbins, 1995). In business, firms (and the CEOs who run them) love a monopoly, particularly when they offer products that consumers cannot afford not to buy, like beer or bread (Jacquemin, 1982). A little competition is good for the consumer.

Nobel laureate Reinhard Selten (1978) described a paradox of competition; it is a paradox because logic dictates that competitors be accommodated, whereas practical wisdom demands aggressive moves like predatory pricing. This is the famous chain store paradox. Suppose Sheila runs a small chain of stores with two locations. Jim is ready to enter the market by opening his own store in one of the two neighborhoods where Sheila is already doing business. If Sheila does nothing, her revenue will be reduced, and Jim will make more money than he would if he did not enter the market. Let’s say Sheila makes five units of wealth, and Jim makes one unit before entry. Now, with Jim’s arrival, Sheila is down to two units of wealth, and Jim is up to two units. Sheila and Jim coexist in the first location, and Jim sees an opportunity also to enter the second location with his own store, making it a chain store as well. The outcome is competition only in the sense that each store makes less profit than it would if it were the only store. Otherwise, this situation would be one of peaceful coexistence.

Now, suppose Sheila fights back with predatory pricing upon Jim’s market entry. Both wind up with zero wealth units gained. The only reason Sheila might do this is to deter Jim from entering the second location and perhaps to make him give up the first. The logic of deterrence requires a shadow of the future. If no future action (i.e., competitive market entry) is possible, aggressive predatory pricing makes no sense. This is the situation with regard to the last chain store location (the second one in this example, but the Nth location in the general case).

The Jims of the world, according to Selten (1978), will realize that the Sheilas of the world will not stoop to predatory pricing when no further deterrence is possible. This means that Jim can safely assume that Sheila will not react aggressively to his last and final store opening. Once this is understood, the logic of backward induction (Shor, 2005) says that no deterrence will occur on the penultimate round of this game, that is, the second to last store location. If accommodation on the last round is assured, there can be no deterrence on the penultimate round. No matter if there are two or 20 locations, Jim and Sheila understand that Sheila will never resort to predatory pricing, and so the consumer will end up finding competing chain stores in each neighborhood.

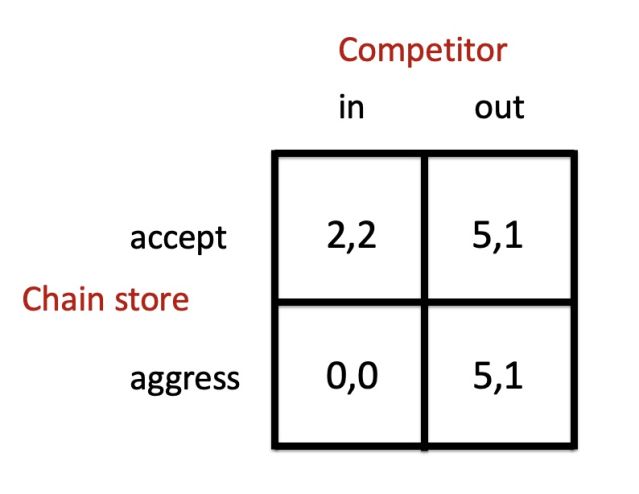

The outcome matrix above shows the payoff structure of this game. Sheila is the row player, and Jim is the column player. Higher numbers mean more revenue, and the numbers to the left of the comma refer to Sheila’s. It is obvious that the situation marked by Sheila’s nonaggression (“accept”) and Jim’s market entry (“in”) is a Nash equilibrium. That is, neither player would be better off by adopting a different strategy.

Whence the paradox? The logic of backward induction only cares about the number of stores (and thus rounds of play) being finite and that both players know this. Without this assumption, deterrence gains no rational footing; it could be reasonably expected to work because there might always be another round for which the would-be competitor could be threatened. The logic of backward induction does not care about the number of stores or rounds of the game. The math always works with finite numbers. Psychologically, however, a longer shadow of the future matters a great deal. The farther an agent or player is asked to look into the future, the harder it is to maintain a clear vision. The future has a way of being discounted by the myopic mind (Loewenstein & Elster, 1992).

Selten himself, as reported by Reb, Luan, and Gigerenzer (2024), confessed that he would have (and probably yield to) a strong impulse in the role of Sheila to try to eliminate Jim’s competition by cutting prices in the first store. Why is that when Selten himself had proven the unassailable logic of backward induction? Reb and colleagues survey a myriad of intuitions, heuristics, and gut reactions, and they show how these nonrational modes of decision-making can yield surprisingly good results, especially in situations of uncertainty. But what are the decision heuristics driving the Sheilas of the world to smother the competition with predatory pricing in a context without any real uncertainty?

I see three possibilities here. One is that aggressive moves worked in the past. Sheila has learned that the Jims of the world can be driven out of the market if Sheila is willing to bear the cost of short-term aggression. This has not just worked in Sheila's own experience, but it is present in the memory of the species from times well before the advent of chain stores. Deterrence works (Smiley, 1988). Another possibility is that Sheila simply does not think through the logic of backward induction. She experiences the impulse to aggress as an obligatory reaction to a challenge to her economic well-being. Lastly, many humans are liable to act out of spite. They are willing to forego gains if they can inflict greater pain on a competitor. This last hypothesis is testable. A spiteful Sheila will aggress against Jim in the last store or even if there is only one. And even this may not be irrational. Jim may give up and try his luck elsewhere, and Sheila can return to her monopoly pricing. All told the psychological puzzle is why economists like Selten even bother to prove what is rational but unreasonable.

References

Jacquemin, A. (1982). Imperfect market structure and international trade - some recent research. Kyklos, 35, 75–93.

Loewenstein, G., & Elster, J. (1992). Choice over time. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Reb, J., Luan, S., & Gigerenzer, G. (2024). Smart management: How simple heuristics help leaders make good decisions in an uncertain world. Cambridge, MIT Press.

Robbins, M. M. (1995). A demographic analysis of male life history and social structure of mountain gorillas. Behaviour, 132, 21-47.

Selten, R. (1978). The chain store paradox. Theory and Decision, 9, 127-159.

Shor, M. (2005). Backward induction. Dictionary of game theory terms. https://www.gametheory.net/dictionary/BackwardInduction.html Accessed: June 18, 2024

Smiley, R. (1988). Empirical evidence on strategic entry deterrence. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 6, 167-180.