Emotional Abuse

Understanding the Mindset of a Human Trafficking Victim

Psychological abuse is more common than physical abuse as a means of control.

Posted April 18, 2023 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Deception, intimidation, and psychological abuse are more common than physical abuse in trafficking cases.

- Family members, friends, and intimate partners are involved in the majority of sex trafficking cases.

- This intimacy further complicates the relationship between the victim and the trafficker.

Co-authored by Brittany Blevins, MPH Student at the University of Southern California

The Seattle Times recently published a story in November 2022 of a 20-year-old woman who jumped from a third-story window to escape her trafficker. He continued to pursue her, throwing her into his car at gunpoint. She was able to escape and was eventually picked up by an Uber driver who took her to get help. Fortunately, this is an example of a young woman who managed to navigate the hurdles to freedom. But what prompted her to make such a dangerous attempt at escape? And why don’t so many of those in trafficking situations try to escape, even when an opportunity presents itself?

At any given moment, there are an estimated 27.6 million human trafficking victims worldwide. Victims of human trafficking can be of any age, nationality, socioeconomic status, religion, immigration status, education level, sex, or gender. The U.S. Department of State reported that victims most at risk include children navigating the welfare system, runaway, and homeless youth, people who have substance use disorders, people with disabilities, and those seeking asylum and/or without lawful immigration status.

There are many complex psychological and physical underpinnings for why a victim cannot, or will not, leave a trafficking situation. While challenges may include confinement/captivity and being closely guarded or monitored, there are more complex reasons to explain why victims may not try to escape even when they have the chance. Acknowledging that deception, intimidation, and psychological abuse are central to this experience helps us understand victims’ decision-making processes. How victims may perceive themselves and the circumstances around them may be affected by their experiences of trauma and living for so long in a heightened survival mode.

Fear encompasses every aspect of a trafficking victim’s life. Mental weapons used by the trafficker to create and maintain control include threats of deportation, threats to harm family or friends, or threats of physical violence. Victims may also be conditioned to fear authority figures or border guards. It is also possible that the victim may be from a country where the authority figures are inherently mistrusted due to corruption. For those who are not intimidated by authorities, there is also the fear of the trafficker carrying out the threats that have been made toward loved ones.

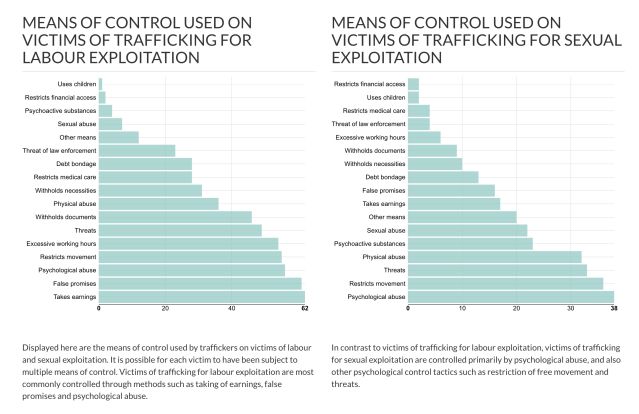

Despite public stereotypes that generally trafficking victims are kidnapped and physically held against their will, the Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative is the first global data hub on human trafficking, collating data from more than 150,000 cases of labor and sex trafficking from around the world. As seen in the chart below, psychological abuse is much more common than physical abuse as a means of control used for victims of both types of trafficking.

A common misconception is that all human trafficking victims are abducted and forced into servitude by people they don’t know. However, as shown in the chart below, family members, friends, and intimate partners are involved in the vast majority of sex trafficking cases, but not labor trafficking cases.

This element of intimacy can further convolute the thought processes of victims. Traffickers place themselves at the center of victims’ lives, present themselves as excellent listeners, or pose as someone who cares deeply in order to create a sense of complete internal dependency, which is much easier to do if the trafficker is a family member or friend. Traffickers are experts at understanding what their victim needs: a physical need, such as a place to stay, or a psychological need, such as a sense of belonging.

The trafficker is in a position of power by providing what the victim is seeking, as well as having the power to threaten to withdraw what the victim wants or needs from them. Many victims don't want to take that risk when considering what kind of situation they will be in if they escape. They have internalized that they need their trafficker in order to have a place to live, food to eat, clothes to wear, and/or affection, love, or intimacy.

Grooming is defined as the process by which traffickers recruit and exploit victims and convince them that they have the power to choose to be participants in their own exploitation. The Polaris Project states that traffickers subtly promote the idea that selling sexual services is normal, acceptable, and necessary. Usually, the exploitation begins slowly, through phrases such as “just this once” or “help me out.” The phenomenon of the boyfriend tactic includes extreme flattery, promises of salvation from the abuse, and ongoing reassurance that they alone are the only ones who can care for the victim. This methodical emotional manipulation is often confused as kindness, which can cloud the judgment of the victim, friends, and family, impeding the ability to recognize a harmful situation (Barnett, 2021).

In social psychology, the fundamental attribution error can help us to understand the more intrinsic factors that prevent a victim from leaving, even in the absence of physical barriers. This is defined as “[T]he tendency to attribute cause to an individual rather than to the situation" (Hassan et al., 2019). Victims may blame themselves for getting duped or getting into a bad situation. Research has also shown that victims may not even realize that they are being trafficked, which is especially the case when the trafficker is someone the victim trusts, like a relative, a significant other, or a friend.

There is also the trauma bonding syndrome, sometimes known as Stockholm syndrome, in which victims will form strong emotional attachments with their traffickers that are the result of cycles of abuse and manipulation. These bonds lead to strong feelings of loyalty of victims towards their traffickers, causing them to justify and rationalize staying. Even when rescued, victims may be unwilling to name or testify against their abusers.

The multifaceted coping mechanisms that victims develop often serve as barriers to self-identification, and to escape. Because many trafficking victims feel indebted to their traffickers, manipulation tactics–against the backdrop of perceived intimacy–can lead to fear, skepticism, and even denial.

References

Barnett, J. (2021, June 16). The boyfriend model of sex trafficking: The lure of false romance. Greenlight Operation. Retrieved February 7, 2023, from https://www.greenlightoperation.org/blog/2021-2-10-the-boyfriend-model-….

Hassan, S.A., & Shah, M.J. (2019). The anatomy of undue influence used by terrorist cults and traffickers to induce helplessness and trauma, so creating false identities, Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 8, 97-107.

U.S. Department of State. (2023, January 18). About human trafficking - United States Department of State. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://www.state.gov/humantrafficking-about-human-trafficking/#:~:text….