Anger

James Gandolfini Teaches Us About the Psychology of Fury

Gandolfini didn't act with anger, he cultivated it.

Posted September 13, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- James Gandolfini was best known for playing the fractious Tony Soprano, and his approach to instilling his character with anger was unique.

- Gandolfini actively cultivated anger, and unleashed this fury into his scenes.

- From both an emotional and cognitive perspective, this kind of "intentional anger" can provide unexpected benefits.

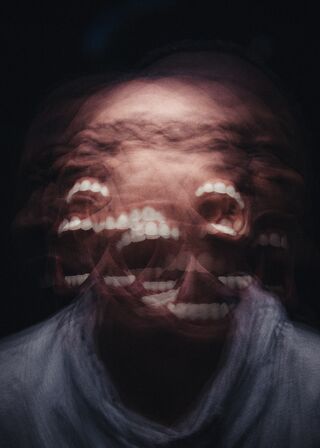

He was only 6 foot 1, but his physical presence filled every room. When his face turned to rage, it was pure and unmistakable. And when it was turned towards you, you simply couldn’t look away. Catching his glare was like looking into the headlights of a Mack truck coming straight towards you.

Such was the experience of being an actor alongside the late great James Gandolfini on the set of "The Sopranos."

Gandolfini played the mob boss Tony Soprano, a legendary acting performance that earned him widespread praise, including three Emmy Awards, three Screen Actors Guild Awards, and one Golden Globe Award. Gandolfini took audiences into Tony’s gangster underworld and the tribulations of New Jersey mob life. And along the way, contending with deep questions of parenthood, morality, and human nature.

Tony is revealed to be a dark, craven, but ultimately complex figure. But perhaps his defining characteristic was his anger. And Gandolfini—a former bouncer in his own right—crafted this to perfection.

How Gandolfini Cultivated Anger

Gandolfini was once asked, “How do you get yourself to act so angry?” His response was telling: He made himself angry. He didn’t feign anger, he cultivated it with a very specific technique: When he knew he had a scene coming up with an angry outburst (and there were many), he slowly built up his anger throughout the day. He would purposely walk around, for the entire day, with a rock in his shoe.

By the time the shoot came, he would unleash all of that accumulated into the scene, and onto his fellow actors. He remarked, “It’s silly, but it works.”

And to a devastating effect. One could argue that there have been better actors at various things, but you’ll be hard-pressed to see anyone do anger better than Gandolfini. The rage feels real because it was real.

Gandolfini isn’t alone, and the usefulness of anger extends far and beyond the world of acting. Athletes, for example, are some of the best at harnessing the motivating power of anger. Michael Jordan was a master at not only harnessing it but finding it. From an opponent’s trash talk, a reporter’s dismissal, or a rival coach refusing to shake his hand in a restaurant, Michael found ample opportunity to “take it personally.” And like the rock in James Gandolfini’s shoe, he channeled this anger into his game.

From acting to sports to art, anger can be an asset. A special fuel. But before we can learn to harness it, we have to answer a more rudimental question: What is anger?

James Gandolfini and The Psychology of Fury

Anger, like all emotions, is an inner subjective experience. And it can be understood from three perspectives: there’s the physiological response (e.g., increased heart rate and breathing), the stereotyped thoughts (e.g., feeling wronged, plotting a response), and the associated behaviors (e.g. the drive to act out against the perceived source). This distinction is key: Not all feelings of anger are necessarily accompanied by specific thoughts or result in specific actions. Anger is a feeling which naturally motivates thoughts and actions, but these are distinct elements and are not inevitable.

What people do with these feelings and physiology, differs from person to person.

We’re generally awful at understanding the reasons why we feel a certain way, a phenomenon known as the misattribution of arousal. And just like all other emotions, anger provides an important signal, which, if understood can help you adjust your behavior or way of thinking.

In everyday life, this introspective element is key. For example, imagine coming out of a meeting with colleagues and feeling a distinct sense of anger. But why? They liked your ideas, and they agreed to use your proposal. Was it a comment that your boss made? Was it an intrusive, anger-inspiring thought about something totally unrelated that just happened to pop into your head? The possibilities are plentiful. But whatever the true answer is, understanding the source can help guide your future behavior.

This is the beauty of the “intentional” anger; the likes utilized by Gandolfini and Jordan: You know the true source of the anger. The attention then turns to learn how to harness it. And once this is achieved, anger becomes not something you’re reacting to, but a tool at your disposal. In this way, anger is like modern technology: a good servant, but a poor master.

This post originally appeared on the marketing psychology blog MJISME

References

Cherry, M. E., & Flanagan, O. E. (2018). The moral psychology of anger. Rowman & Littlefield.

Itzkoff, D. (June, 2013). "James Gandolfini Is Dead at 51; a Complex Mob Boss in 'The Sopranos'". The New York Times.

Jordan, C (June, 2013). "In Jersey, Gandolfini remembered as regular guy". USA Today.

NJ Spotlight News (June, 2013) James Gandolfini Was a Jersey Guy Who Helped Change Television, https://www.youtube.com/watch

Nussbaum, E. (June 20, 2013). "How Tony Soprano Changed Television". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020.

Martin, R. (February, 2021) How to be angry, Psyche Magazine