Cross-Cultural Psychology

Most Languages Are Not English

Research conducted in WEIRD countries shouldn't be seen as generalizable.

Updated December 9, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Psychology experiments conducted in WEIRD countries may not generalize to the rest of the world.

- For language researchers, a similar situation emerges, with most studies focusing on English.

- The English language is only one of 7,000 languages and doesn't have the most native speakers.

- Tools are now available to analyze 40 languages other than English and compare the findings across languages.

Something has been going wrong with psychology experiments. Only 12 percent of the world’s population is from Western industrialized countries—yet 96 percent of the participants in psychology experiments are from Western industrialized countries. The question can therefore be raised to what extent the findings from the many psychology experiments conducted each year can be generalized across the entire population—from the 12 percent to the 88 percent.

Take, for instance, the theory of attachment—the relationship with at least one primary caregiver for normal social and emotional development in children and the importance of a secure base. The theory is very much based on measures of sensitivity and security biased toward a Western view—no wonder given the participants in experiments. According to that view, a child's autonomy, individuation, and exploration are emphasized.

But in other parts of the world, for instance in Japan, team spirit and collaboration are considered more important. Securely attached children communicate their emotions more openly—this is considered positive in the Western world but is frowned upon in Japan.

Or take the field of numerical cognition, which studies the cognitive, developmental, and neural aspects of numerical and mathematical thinking. Whereas the Western world organizes time, size, and numbers from left to right, indigenous people of lowland Bolivia organize numbers in either direction. These cross-cultural differences can have a major impact on psychological theories—for instance, the theory of spatial numerical association of response codes (SNARC), which claims that we use a mental number line in our mathematical thinking with low numbers on the left and high numbers on the right.

The importance of being sensitive of generalizing across a population was acknowledged over a decade ago when psychologists argued that most people are not WEIRD—that is, they are not from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) societies—and that findings particularly from American undergraduate student participants can perhaps not necessarily be generalized.

Languages Are Not WEIRD, Either

For language research, things are not much different than for the participants in psychology experiments. The vast majority of the psycholinguistic and computational linguistic studies are based on English as the target language.

It is easy to generalize the findings found for the English language to other languages. We might be able to draw conclusions with regard to language acquisition, language processing, and language disorders. We might use the language input for social psychological theories, clinical practices, or language models for artificial intelligence.

However, the English language is only one of over 7,000 languages in the world, and not even the one most commonly used by native speakers. English can therefore not at all be prototypical for those 7,000 other languages.

In fact, half of the languages spoken across the world have a very different structure than English. For instance, English has a subject-verb-object (SVO) word order, which is common among Indo-European languages. But that order is very different for 58 percent of the languages in the world that have other word orders (SOV is the most common, but not the only order). Drawing generalizable conclusions on syntactic structures requires taking into account these structures.

Or take another example. English lacks grammatical gender. Contrary to about 50 percent of the languages in the world that do have grammatical gender, in English we do not say “the organization and her employees” or “the book and his pages.” One can imagine that assigning grammatical gender to a word may have an effect—no matter how little the effect may be—on the meaning of that word.

Here is another one. Approximately 60 to 70 percent of the world's languages feature case systems. For those languages, you can easily state that John kissed Mary, but marked by a case system, it is clear that it was Mary who did the kissing. English is not one of them, as word order determines who did what to whom.

Language Relations

Perhaps it is no surprise that language researchers primarily analyze English. When psychologists were limited to offline experiments, it was no wonder that experiments were primarily conducted with English participants. When online experiments emerged, it became easier to access participants across the world, moving away from the WEIRD population.

Language researchers in psychological and computational fields have pretty much been bound by English because they simply did not have the tools for other languages. Those text analysis software packages out there primarily focus on English. Investigating languages other than English was harder, and comparing languages was almost impossible.

Recently, we published an article that aimed to change that. A tool, dubbed Lingualyzer—a linguistic analyzer—analyzes several dozens of languages across hundreds of features, the same 351 multidimensional linguistic measures across 41 different languages. This allows for an easy way to compare languages or to analyze one text written in one specific language.

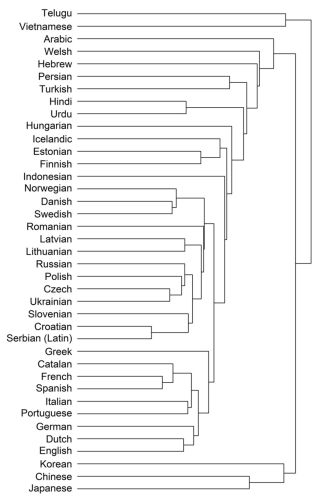

The 7,000 or so languages of the world are organized in language families, with brother/sister languages that are more related because they historically stem from the same parent language. Having this tool, we were now able to understand the relations between some of these languages.

One could look at these language families from an evolutionary or linguistic perspective, as historical linguists have done. But it might now also be possible to look at these language families from within the languages. In order to do this, ideally what one needs is parallel texts, a text that has the same content translated in multiple languages.

Take, for instance, United Nations texts: They need to be stated in exactly the same way across multiple languages. We took texts from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, translated across 41 languages, and asked Lingualyzer to analyze these texts on a large number of dimensions, and we clustered these languages based on the linguistic findings. The results were exciting: The clustering of the languages was very much in line with the clustering so-called typologists conducted when considering the genetical relationships across languages.

Studies like these show empirically which languages have close ties with other languages. But more importantly, they allow for moving beyond WEIRD languages.

Just like experimental psychologists and clinical psychologists ought to be careful generalizing from a WEIRD population, psycholinguists, cognitive scientists, and other language researchers ought to be careful generalizing from a WEIRD language. Thanks to some easy-to-use computational tools, this now becomes more feasible.

References

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (2022). Ethnologue: Languages of the world (25 ed.). SIL International.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83.

Louwerse, M. (2021). Keeping those words in mind: How language creates meaning. Rowman & Littlefield.

Hutchinson, S., & Louwerse, M. M. (2014). Language statistics explain the spatial–numerical association of response codes. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21, 470-478.

Linders, G. M., & Louwerse, M. M. (2023). Lingualyzer: A computational linguistic tool for multilingual and multidimensional text analysis. Behavior Research Methods, 1-28. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.3758/s13428-023-02284-1.pdf

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Pott, M., Miyake, K., & Morelli, G. (2000). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55(10), 1093-1104.