Stress

Luck in War and the Sorrows of What Might Have Been

War is where the randomness of fate may be most salient and disturbing.

Posted February 20, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- War accentuates the random, uncontrollable factors that often decide life and death.

- A memoir by James Keresey of his experiences as a PT boat captain in WW II is a good example of this truth.

- The many senseless deaths led Keresey to conclude that luck was perhaps the biggest factor in survival.

Soldiers must contend with the random, uncontrollable, seemingly absurd factors often deciding whether they live or die.

I think one of the best portrayals of this aspect of war is a memoir by James Keresey, PT 105, in which he describes his time serving as captain of a PT boat in the Solomon Islands during WW II.

.jpg?itok=7G0GVEf1)

Like many of his generation, Keresey was swept up in the tide of events that placed him on the front lines of the war. A zigzagging, jumble of events led him to this PT boat command, something he had neither planned for nor expected.

The conditions of training bore little resemblance to those present in the Solomon Islands. Much of the useful learning occurred only when engaging in actual missions in which mistakes often provided the most important lessons — if one survived these mistakes.

Initial training happened during the day, for example, whereas most PT boat missions happened at night and in complete darkness. This meant extremely difficult, error-prone navigation. All kinds of unfortunate, mostly impossible-to-avoid mishaps occurred. Not infrequently, in the frenzied, terrifying chaos of battle, “friendly” fire would result in men dying.

There were so many senseless, haphazard ways that men perished. One of Keresey’s crew was killed because protective armor plating had been removed from the boat’s cock pit and never replaced.

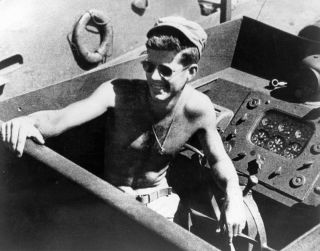

Unreliable radio communication was thought to explain in part why a particular, very famous PT boat disaster occurred, that of Jack Kennedy’s PT 109. Keresey, in fact, was part of a group of boats, including Kennedy’s, that was sent out in an ill-fated, fiasco of a night mission. Some of the boats had engaged Japanese destroyers, and there had been panicked radio communications that might have alerted Kennedy’s boat. However, Kennedy’s radio equipment was, unhappily, not functioning well, probably contributing to why a Japanese destroyer rammed his boat without warning, cleaving it in two and creating a powerful fuel explosion (immediately killing two ill-fated crew members).

Kennedy's remaining crew survived. The several-day ordeal then suffered by these men is now part of the Kennedy legend, and indeed, Kennedy’s remarkable leadership, will, and daring were critical in their survival. But luck also had a big part to play.

Keresey describes so many senseless deaths. His PT boat squadron collected a group of Japanese sailors who were found clinging to the wreckage of their sunken ship. These sailors were treated with respect and given water and cigarettes, even though it was well known that American POWs were usually tortured or executed by the Japanese. They were transferred to a large boat to be taken to a POW camp. After the transfer, a seaman named Raymond Albert offered one of the prisoners some water and the prisoner took this opportunity to grab Albert’s gun and shoot him fatally, before he was then shot dead by guards.

And so, compassion was rewarded with death, a particularly cruel twist of fate for Albert. Moreover, he had been a surviving member of Jack Kennedy’s 109 crew!

Keresey wrote, “...in the thousands of snapshot moments from that war, probabilities gave way to luck. Believe me, luck exists. – and we treated it with great respect. When it comes to individual survival, luck outranks skill, experience, and cowardice.” (p. 74)

As a reader, I found Keresey’s many examples of luck determining survival disturbing in the extreme.

Especially disturbing were the details about the men with whom Keresey served and the contrasting accounts in which good, courageous, competent men died – and other, similar men did not. Those who did survive usually went on to live full and happy lives (Keresey, himself, was an example, as he wrote the book late in his own rich and fruitful life), leaving me with a keen and raw sense of what might have been for those admirable men who perished.

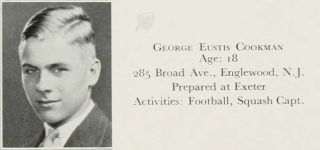

George Cookman, a squadron executive officer and Keresey’s good friend, was, like Albert, one of the unfortunate ones. To Keresey, he was the “complete” PT officer. A recent Yale graduate, he was an appealing blend of confidence, decency, good humor, and courage. He even volunteered for extra missions.

Early in the Solomon Islands campaign, during one night mission in which his boat was in the lead, Cookman was hit and killed by enemy gunfire. He had been standing at the highest position in the boat in order to see the enemy boats better in the darkness — but this meant that he caught the initial gunfire.

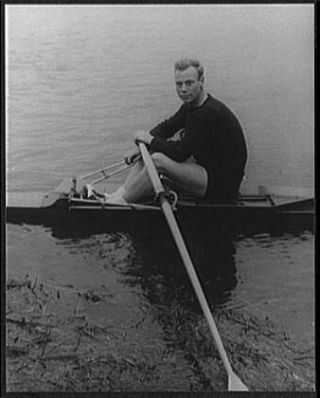

Contrasting the sad, unfortunate death of George Cookman was the survival of Joe Burk. Burk was a Penn graduate, where he had been a champion rower, so outstanding that he would have represented the U.S. in the 1940 Olympics if the games had not been canceled because of the war. Burk was a fearless, unusually effective PT boat commander and highly decorated by the end of his service.

After the war, Burk returned to competitive rowing and then to coaching, at Yale and then at Penn. There is a bronze sculpture honoring him in front of the Penn boathouse. He died at 93 after a full life.

George Cookman never had the chance to live out such a life.

And neither did James Burk, Joe Burk's younger brother. James also rowed for Penn and also became a PT boat skipper in the Pacific.

He died when American planes attacked his boat by mistake.

As Kurt Vonnegut, himself a WW II veteran who had seen the worst of war, famously wrote, “So it goes.”

References

Keresey, J.K. (2003). PT 105. Naval Institute Press.