Punishment

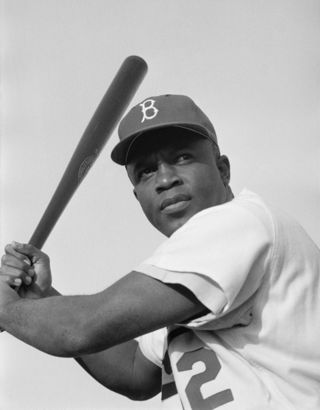

Jackie Robinson and a Revenge Best Served Cold

How can revenge, so full of natural passion, feel best when delayed?

Posted April 3, 2018

Retaliating against someone who has wronged us can be keenly pleasing. Contemporary norms against revenge might counter the pleasure, shaming us for our vengeful actions, but there is no denying the passion human beings have for revenge and the sweetness of its consummation.

Is revenge a sweeter dish when served cold?

I’ve come across no research on this claim, but does it make sense?

With quick, heated revenge, we may hurt ourselves more than the wrongdoer. We might overreact and then seem more the bad actor. Also, the intense swirl of reactions to the wrongdoing may prevent an appreciation of its full features and undermine a working through of the most satisfying way to retaliate. Arguably, the passage of time enables a more level-headed assessment of both the wrongdoing and a more fitting, gratifying retaliation. For example, in our retaliation we may dearly want the offending party to realize the precise features the offense -- and that we are therefore retaliating exactly because of these features. Time provides the opportunity for good planning, turning fantasies of revenge into reality. Our revenge, if achieved more dispassionately may indeed be more pleasing, mixing thought with well-baked but cooled-down desire. The best Hollywood revenge dramas let the hero retaliate with some time on the clock. The final sequence of events is as much cerebral as impulsive, as our hero takes control, looks the villain in the face, and enacts justice with a measure of calm deliberateness.

Sometimes, the delay in retaliation is imposed by circumstances. My favorite example is the case of Jackie Robinson's revenge against Enos Slaughter in the early years of his path-breaking career in major league baseball. Robinson knew, as the first Black player, that he would receive a lot of abuse, especially at first. And despite being an intensely competitive man (as his later years in the league bore out), he suppressed his retaliatory actions when confronted with all manner of taunts.

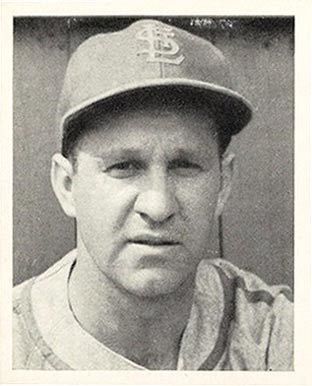

Enos Slaughter tells the story of when his St. Louis Cardinal team was playing Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers in August of 1947 during the first year of Robinson’s entry into the league (Slaughter doesn’t come across well in the story, suggesting that his account is likely true). Slaughter was from the segregated South and didn’t like Robinson’s presence in the league, a sentiment he didn’t hide. During one at bat, Slaughter hit a grounder to Robinson who was playing first base. Robinson easily reached the first base bag ahead of Slaughter, who then deliberately spiked Robinson's ankle, drawing spurts of blood. Slaughter punctuated this with a racial slur. Robinson’s response was simply to say, “I’ll remember that.”

In another game, about two years later, Slaughter hit a single so sharply that it hit off the wall and he tried to stretch it into a double. Here’s what happened next, in Slaughter’s own words:

“Robinson was playing second then. I went sliding in, and Robinson took the throw from the right fielder. He made no attempt to tag me on the leg for the putout: which he could have done easily. Instead he whirled around and smacked me in the mouth with the ball in his glove. Six teeth went flying, there was blood all over me, and I later had to have gum surgery. As he walked away, Jackie said, ‘I told you I’d remember.’”

I don't know for sure how precisely planned Robinson's revenge was, but I would imagine that Robinson took keen pleasure in its completion. Interestingly, he found a way to enact his revenge in public, yet without it appearing to have been done on purpose -- avoiding the social censure of being “vengeful.” I have to admit that I find the story pleasing myself.

A few side notes.

Slaughter told this story to the talk show host Larry King, who, like me, also thought it likely true because it was so unflattering to Slaughter. However, this was many years after the incident, and Slaughter evidently regretted both his actions and his early racist views.

We also have an account of the incident from Robinson’s teammate, Ralph Branca, who was pitching for the Dodgers. Branca told Robinson that he would hit Slaughter with a pitch his next time up, even though he was working on a perfect game. Robinson didn’t want him to do it, preferring that he keep on pitching as he would normally. Robinson noted years later how much the mistreatment he suffered brought his team together.

Finally, it’s worth stressing what an important contribution to American history was Jackie Robinson’s entry into the major leagues. I watched a recent interview with Larry King, who noted that Martin Luther King had once corrected him for making what he considered a historical error. King had introduced MLK as the founder of the American civil rights movement. MLK demurred, saying that the real founder was Jackie Robinson.

Here’s to you, Mr. Robinson!

References

Chester, D.S. (2017). The role of positive affect in aggression. Psychological Science, 26, 366-370.

McClelland, R.T. (2010). The pleasures of revenge. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 31, 193-235.