Career

Sabotage in Academia

Understanding the nature and causes of sabotage in academia.

Posted August 2, 2018

Sabotage in the workplace is not something we think about every day, and it might seem strange to think about sabotage behaviours playing out in academic work settings. Sabotage has been described as any form of behaviour that is intentionally designed to negatively affect service (Harris and Ogbonna, 2002 p. 166). Worryingly, 85% of service employees consider sabotage to be an ‘everyday occurrence’ in their organisations (Harris and Ogbonna, 2002). When researchers investigate employee performance in academia, they tend to focus on research performance (Edgar and Geare, 2011), or the relationship between research performance and teaching quality (Cadez et al., 2017). They rarely think about sabotage. In a recent paper using collective intelligence methods, we explored the nature and causes of sabotage in Academia.

Academia isn’t what it used to be. Academics are facing more challenges to their performance than ever before, including a push for ‘value for money’ (Kinman and Wray, 2013), as well as greater workloads and more isolation (Shaw, 2014). These challenges have resulted in increased role stress (Winefield and Jarrett, 2001), and lower propensity to remain on the job (Su and Baird, 2017). Similar challenges have been identified as causes of sabotage in other sectors (Harris and Ogbonna, 2006). However, we know very little about sabotage in the university sector. Like other organisations, Universities have to work very hard to build their brands. As sabotage behaviours are known to actively work against the organisation’s brand (Harris and Ogbonna, 2002), it would seem timely that we have investigated the nature and causes of sabotage among University academics.

In our study, we conducted three separate collective intelligence (CI) sessions with a total of 23 academics. Each session lasted for three hours. Each group was asked to generate ideas in response to the following question: What are the key components of sabotage among University academics? Each participant wrote their ideas down privately, and then posted their key ideas on an idea wall. All ideas were clarified in turn and each participant was then asked to select five components of sabotage that they believed were the most salient. These steps were then repeated to identify the causes of sabotage, and each group used Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) (Warfield and Càrdenas, 1994; Warfield 1976), to structure the relationship between these causes and a structural model was generated, which illustrated the logic of the group (i.e., a systems based understanding of how different causes of sabotage are related). When we synthesised results across the three collective intelligence sessions, a picture began to emerge as regards the nature and causes of sabotage in academia.

What are the components of sabotage in academia?

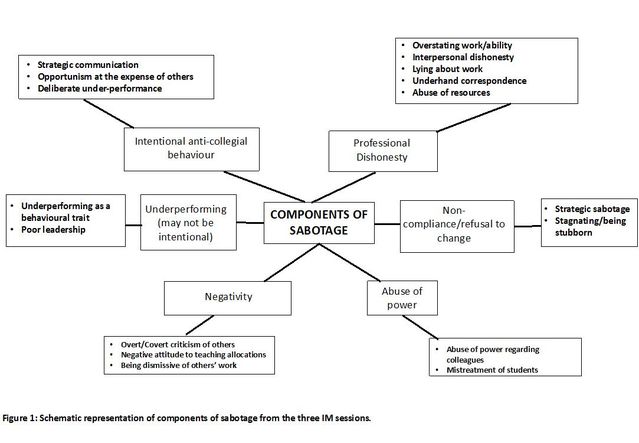

Analysis of all the components of sabotage revealed six high-level dimensions of sabotage behaviour in academia (see Figure 1):

(i) Intentional anti-collegial behavior, such as opportunism at the expense of others.

(ii) Professional dishonesty, such as lying about work or abusing resources.

(iii) Non-compliance, such as being stubborn, or refusing to change.

(iv) Abuse of power in interactions with staff or students.

(v) Negativity, including criticism of others, or being dismissive of others’ work.

(vi) Underperforming, such as poor leadership.

The causes of sabotage

In order to understand the causes of these sabotage behaviors we analyzed all the ideas generated by the groups. Six high-level themes were identified, each of which included a set of causes related to:

(i) Self-interest

(ii) Personality traits

(iii) Personal issues related to the role itself

(iv) Extraneous stress

(v) Managerial practices

(vi) The culture of the organisation

Each theme is illustrated below by reference to one of their informing ideas:

Self-Interest (example: learned behaviour): “(one learns that) sabotage is what you have to do in order to get to the top….(saboteurs) are a product of their experience, they’re a product of what they’ve seen, how other people have behaved to get where they want to be” (Female participant),

Personality traits (example: too much ambition): “a motivation or drive to gain status, resources, et cetera, and…put somebody else down in order to gain those for yourself” (Female participant).

Personal issues related to the role itself (example: role conflict): “you can’t deliver on everything in a timely fashion ... then that could lead to conflict’ (Male participant).

Extraneous stress (example: pressure): many participants talked about difficult personal circumstances or personal stress as a possible cause of sabotage.

Managerial practices (example: no system of accountability): “if you turn up late to a meeting, nobody says anything…If you don’t take the class, who’s going to say anything? You’re not accountable to anybody” (Male participant).

The culture of the organization (example: a mismatch between personal and organizational values): “I’m not necessarily seeking to attract resources or reputation deliberately at the expense of others, but…I might resist certain things I’m told I’m required to do… I don’t do some work, and therefore it falls on other people’s shoulders” (Male participant).

How are these causes of sabotage related?

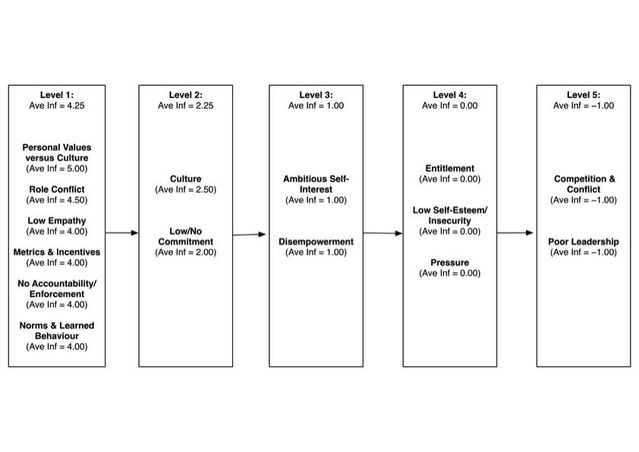

Each group generated a structural model describing how top voted causes of sabotage are related. Then, a meta-analysis of these structures was generated, using the structural influence scores for the full set of 18 causes of sabotage that emerged across all sessions (see figure 2).

Working from left to right, figure 2 indicates that the clash between personal values and cultural values, role conflict, low empathy, metrics and incentives, no system of accountability or enforcement, and norms or learned behavior each negatively influence low commitment and a culture conducive to sabotage. In turn, these causes negatively influence ambitious self-interest and disempowerment, which then influence entitlement, low self-esteem and pressure. Collectively, these causes negatively influence competition and conflict and poor leadership.

Figure 2: Meta-analysis of causes of sabotage.

How could sabotage be minimised?

To combat these causes sabotage, we suggest the following actions:

- Senior managers seeking to optimize employee performance should set out clear guidelines for performance and progression, and put in place clear incentives and reinforce values.

- Additional structural supports within the University sector could help to overcome role conflict, and current perceptions of a lack of accountability or enforcement.

- Employee training should support understanding the values and direction of the University, and guidance for managing any perceived mismatch between personal and organizational goals.

- As a form of job enrichment and empowerment, academic units could develop their own values. By developing values at unit level, this may encourage buy-in from academics, and a greater ‘esprit de corps’.

- Providing more mentorship and support, including review and feedback sessions, could help to encourage greater employee commitment to their roles.

- By supporting employees to have a feeling of perceived control, managers may help to minimize employees’ feelings of disempowerment.

- Managers should be provided with training and specific methods that help them to recognize employees’ pressures, and offer ways to alleviate them. For example, managers can offer opportunities for academics to talk about their work pressures by providing common areas for academic staff to meet informally, and ensuring an open dialogue with employees.

In summary, our study provides an initial framework for understanding the nature and causes of sabotage in academia. This framework can be used to inform theory development and intervention work in this area.

Elaine Wallace, Michael Hogan, Chris Noone, Jenny Groarke

References

Cadez, S., V. Dimovski, and M. Zaman Groff. 2017. “Research, Teaching and Performance Evaluation in Academic: the Salience of Quality.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (8): 1455–73.

Edgar, F., and A. Geare. 2011. “Factors Influencing University Research Performance.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (5): 774–92.

Harris, L. C., and E. Ogbonna. 2002. “Exploring Service Sabotage: The Antecedents, Types, and Consequences of Front- Line, Deviant, Antiservice Behaviours.” Journal of Service Research 4 (3): 163–83.

Harris, L. C., and E. Ogbonna. 2006. “Service Sabotage: A Study of Antecedents and Consequences.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34 (10): 543–58.

Kinman, G., and S. Wray. 2013. Higher Stress: A Survey of Stress and Well-Being Among Staff in Higher Education. London: University and College Union.

Shaw, C. 2014. “Overworked and Isolated – Work Pressure Fuels Mental Illness in Academia”, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2014/may/08/w… (accessed 1st August 2018).

Su, Sophia, and K. Baird. 2017. “The Impact of Collegiality Amongst Australian Accounting Academics on Work-Related Attitudes and Academic Performance.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (3): 411–427.

Warfield, J. N. 1976. “Implication Structures for System Interconnection Matrices.” Systems, Man and Cybernetics, IEEE Transactions 1: 18–24.

Warfield, J. N., and A. R. Cardenas. 1994. A Handbook of Interactive Management. 2nd ed. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

Winefield, A. H., and R. Jarrett. 2001. “Occupational Stress in University Staff.” International Journal of Stress Management 8: 285–298.