Intelligence

The Adaptive Functions of Music Listening

Why People Listen to Music

Posted July 16, 2015

Music is a profound act of human creation. Music can transform our ongoing psychological state in an instant, and potentially enhance psychological functioning across the lifespan. Whether it be classical music, hip-hop, jazz, Latin, opera, rock, reggae, dance or country music, people all over the world respond to music in characteristic positive ways and are highly motivated to innovate new musical experiences. The purported healing properties of music have been celebrated since the 6th century when the philosopher Pythagoras began prescribing music as a medicine to restore harmony to the human mind, body, and soul. While you might have a hard time convincing your doctor to write you a prescription for a Led Zeppelin record these days, we bet you can recall music that helped you through difficult times in your life, and we bet you know a song or two that remind you of the happiest moments in your life. At the same time, high quality science is needed to clarify the purported benefits of music listening. Research has highlighted the importance of music listening for younger adults1, 2 and older adults3 in promoting quality of life and managing psychological distress. However, less is known about the full range of adaptive functions of music listening and how these adaptive functions promote well-being and enhance quality of life. This prompted us to investigate this question using a collective intelligence research methodology.

What are the Adaptive Functions of Music Listening?

Research has highlighted mood regulation to be the most important function of music listening4, but people also listen to music for its cognitive benefits, such as increased focus and attention, the experience of cognitive complexity, to facilitate social interaction and bonding, and reinforce social identity5-8. More recently, research has started to focus on how music promotes wellbeing, which we can think of as simply the hedonic balance of positive and negative emotions, or more broadly in terms of our life engagement, meaning, and overall psychological and social well-being. It seems that beyond hedonic well-being, the broader, so-called “eudaimonic” aspects of wellbeing become more important as we age9,10, but we know very little about how music interacts with these aspects of wellbeing. Research does suggest, however, that music brings about not only pleasure but also absorption and transcendence in listeners11,12, so it is worth considering how music enhances wellbeing in the fullest possible sense, drawing upon the rich collective intelligence of experienced listeners.

Tell us why YOU listen to music! Take the AFML survey here.

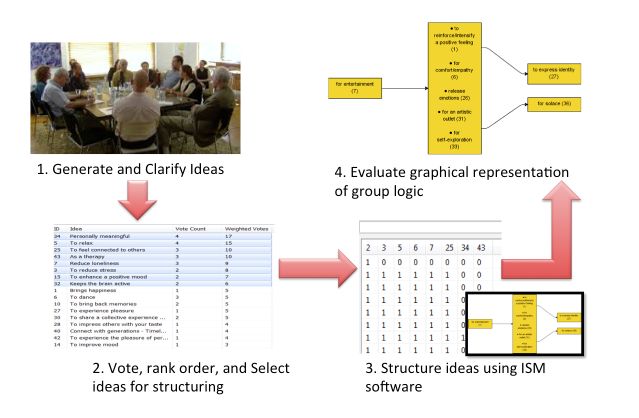

In our research, we were interested in finding out why younger and older adults listen to music, and how these functions of music listening interact to enhance wellbeing. We used a collective intelligence method called Interactive Management (IM) to ask 25 young adults (18-30 years old) and 19 older adults (60-75 years old) about why they listen to music, and to model how these functions of music listening interact. The IM process involves four steps: (1) Generating ideas in response to a trigger question (e.g., Why do you listen to music?), (2) Voting and selecting ideas (e.g., which of these functions of music listening are most important for enhancing your well-being?), (3) Developing a systems model through a matrix structuring of relationships between ideas (e.g., by asking a series of questions of the type: does music function A significantly enhance your ability to benefit from music function B?), and (4) Evaluating the logic of participants by recording and analysing their dialogue and thinking (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Steps in the Interactive Management (Collective Intelligence) Process

Music and Wellbeing across the Lifespan

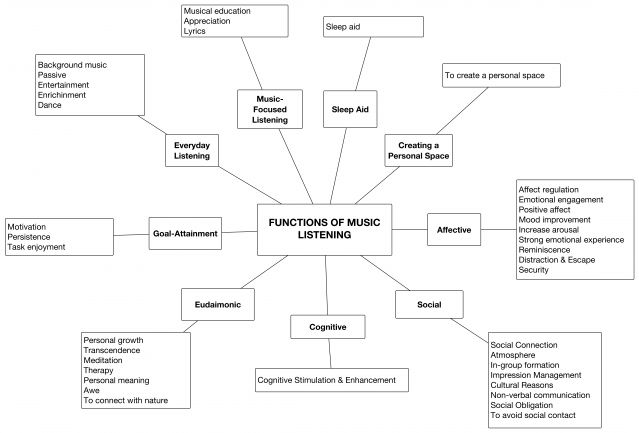

Our IM sessions generated 138 functions of music listening, which we organized into 9 broad themes (see figure 2). The primary functions addressed mood, social, cognitive, and eudaimonic aspects of music listening, and also functions such as goal attainment, music analysis, aiding sleep, and creating personal space. Younger adults spoke mainly about how listening to music helps them to regulate their moods, achieve important personal goals, and reminisce in a variety of ways. Conversely, older adults focused more on how music fosters positive moods, social connections, and transcendence.

Figure 2. A category analysis of the adaptive functions of music listening

While both younger and older adults emphasized the importance of music in bringing about strong emotions, these emotions had a more positive, transcendent quality for older adults, who consistently spoke about music taking them to "another world", "a different dimension", and "transcending the mundane". Transcendent experiences are functionally significant and have been related to benefits such as increased happiness and meaning in life13, higher life satisfaction14, and reduced loneliness in older adults15. Indeed, for the older adults in our study it seems that listening to music plays an important role in easing feelings of loneliness. At the same time, while older adults spoke about using music to reduce feelings of isolation, younger adults spoke about how music allowed them to carve out a personal space where they could limit social connection. As one young woman described it, “When I’m listening to music, I can escape sort of, even though there’s people around... I can escape that stress,” (Female, 24). It seems that while younger adults may be using music to ease the stresses associated with their active social lives, older adults may listen to music to compensate for their feelings of social isolation.

Both age groups discussed using music to aid reminiscence. Analysis of the collective intelligence transcripts revealed that reminiscence is linked to personal growth and empathy for older adults, whereas for younger adults reminiscence may serve self-regulatory functions that facilitate coping with life. For example, while older adults spoke about listening to music to bring back fond memories such as “lovely memories of a particular person that may have passed on” (Female, 65), younger adults described using music to consciously remember significant others, for example when feeling homesick, and even for less adaptive reasons such as “break-up songs, just to torture yourself” (Female, 22). In relation to personal growth, older adults described music as enhancing reflection which, in turn, helped them to foster feelings of compassion for themselves and others.

Our study was the first to use Interactive Management to explore the connections between music listening and wellbeing, and consider how the functions of music listening may differ between younger and older adults. It appears that both older and younger adults believe that music has an effect on their wellbeing. A meta-analysis of the systems thinking of younger and older adults highlighted the importance of intense emotional experiences, reminiscence, and eudaimonic experiences such as meaning and transcendence in driving all other adaptive functions of music listening. These aspects of music listening function adaptively to enhance feelings of wellbeing across the lifespan, in old and young alike. You can read the full version of our paper and collective intelligence analysis here.

Retweet this article @JennyMGroarke and tell us why YOU listen to music!

We are seeking a large number of volunteers aged over 60 years to complete a questionnaire for the next phase of our study. You can take our survey of adaptive music listening here: http://www.surveygizmo.com/s3/2101829/BL

Please RT, Like and Share!

For more information visit our site at: http://adaptivefunctionsofmusic.com/

Find Jenny Groarke and Michael Hogan on Twitter

References:

- Miranda, D., & Gaudreau, P. (2010). Music listening and emotional well-being in adolescence: A person- and variable-oriented study. European Review of Applied Psychology, 61(1), 1-11.

- Saarikallio, S. (2011). Music as emotional self-regulation throughout adulthood. Psychology of Music, 39(3), 307–327. doi:10.1177/0305735610374894

- Laukka, P. (2007). Uses of music and psychological well-being among the elderly. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(2), 215–241. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9024-

- Juslin, P. N., & Sloboda, J. A. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications. Oxford University Press.

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2007). Personality and music: Can traits explain how people use music in everyday life? British Journal of Psychology, 98(2), 175–185. doi:10.1348/000712606X111177

- Chin, T., & Rickard, N. S. (2012). The music USE (MUSE) questionnaire: An instrument to measure engagement in music. Music Perception, 29(4), 429-446.

- North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & O'Neill, S. A. (2000). The importance of music to adolescents. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 255–272.

- Huron, D. (2001). Is music an evolutionary adaptation? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1–19.

- Ryff, C. D. & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13–39.

- Piedmont, R. L. (1999). Does spirituality represent the sixth factor of personality? Spiritual transcendence and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality, 67,

- Seligman, M. E. (2002). Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realise your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

- Beaumont, S. L. (2005). Identity processing and personal wisdom: An information- oriented identity stlye predicts self-actualization and self-transcendence. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 9, 95-115.

- Gillham, J., Adams-Deutsch, Z., Werner, J., Reivich, K., Coulter-Heindl, V., Linkins, M., et al. (2011). Character strengths predict subjective well-being during adolescence. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 31–44.

- Walton, C. G., Shultz, C. M., Beck, C. M., & Walls, R. C. (1991). Psychological correlates of loneliness in the older adult. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 5, 165–170.