Hypnosis

Hallucinated Colors Produce Real Color Afterimages

Participants hypnotized to hallucinate red experienced blue-green afterimages.

Posted March 30, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Color afterimages have long been thought to be driven by early neural mechanisms at the level of the retina.

- A new study used hypnosis to induce highly suggestible participants to hallucinate red for 30 seconds while staring at a gray screen.

- The hypnotic induction led participants to experience color aftereffects (i.e., seeing green or blue) in a subsequent gray screen.

- This effect was significantly weaker in a different group of highly suggestible participants who were just asked to imagine red with no hypnosis.

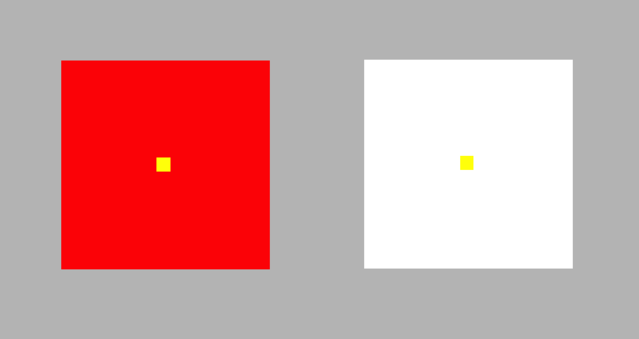

One of the earliest discoveries in perceptual psychology was the existence of color afterimages. For example, the square below on the right is clearly white. But if you first stare at the red square for about 30 seconds and then glance at the square on the right, you should experience a greenish-blue or cyan afterimage.

The discovery of such color afterimages (or aftereffects) was incredibly consequential in our understanding of color processing, leading Ewald Hering to develop the opponent-process theory in 1878 – the idea that we process colors via opponent channels that respond positively or negatively to opposing pairs of colors (e.g., red vs. green, blue vs. yellow, and white vs. black). These opponent channels have long been thought to be implemented at the earliest stages of visual processing in the retina itself.

However, a new research study published in Perception by Oksana Sivkovich Fagin and Arien Mack challenges this assumption. The researchers used hypnosis to show that color afterimages can be produced entirely by higher-level cortical mechanisms. In their first experiment, 100 participants were screened for suggestibility using the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Suggestibility: Form A (Shor & Orne, 1962).

Fifteen participants were selected as being highly suggestible. These participants underwent hypnotic induction and were told that when they opened their eyes, they would see a red screen. In fact, the screen was always gray.

Once the hypnotized participants confirmed they were seeing red, they were instructed to keep looking at the "red" screen for another 30 seconds. Afterward, a new, slightly lighter gray screen appeared, and participants were asked to quickly name the color they saw. The striking result was that of the 11 participants who reported seeing red during the hypnotic induction, ten of them reported the color of the second gray screen as being green or blue, consistent with what would be experienced as a real afterimage of red.

The four participants who did not hallucinate red did not report any color afterimage at all. Importantly, only three of the eleven participants who hallucinated red knew that its aftereffect was supposed to be green, although they all reported the aftereffect as bluish rather than greenish. This suggests that the results are not likely to be driven by particiapnts' prior knowledge about color afterimages.

Hallucination is distinct from mental imagery

In a follow-up experiment, the researchers examined whether similar afterimages would be produced if participants simply imagined a color without undergoing hypnosis first. Using a similar procedure, the researchers screened 150 new participants to select the 15 most suggestible. Those participants did not undergo hypnosis but were simply instructed to imagine red when looking at the first gray screen for 30 seconds.

Then, when a second gray screen was presented, they reported any color they saw. Although all 15 participants reported being successful at imagining red, only five reported seeing a blue or green aftereffect in the second gray screen; another five reported seeing pink (inconsistent with a color afterimage), and the remaining five reported seeing just a shade of gray. A statistical analysis confirmed that the hypnotized group in the first experiment experienced blue/green color afterimages significantly more than the non-hypnotized group.

The results of this research are groundbreaking because they demonstrate that real color afterimages can be produced in the absence of real color adaptation. This means that the opponent channels thought to account for color afterimages cannot exist solely in the retina but must also manifest at higher levels of cortical processing that can be engaged by hypnotic suggestion.

Still, the study leaves some questions open for future research. For example, with real color adaptation, we know that longer periods of adaptation lead to stronger color afterimages. Is the same thing true for hallucinated colors? In other words, does hallucinating red for 60 seconds produce stronger or longer-lasting color aftereffects than hallucinating red for just 15 seconds? If so, it would provide further evidence that the mechanisms of hallucinated color adaptation are similar to the mechanisms of real color adaptation.

The research study also leaves open the question of what happens at the neural level when someone is hypnotized to see a color that isn't there. An earlier study by Kosslyn et al. (2000) examined brain activations when highly suggestible participants were either asked to imagine a color or hypnotized to hallucinate a color. When imagining a color, participants showed activation in the right hemisphere color area.

But when hallucinating a color, both the right and left hemisphere color areas were activated, similar to what happens when a real color is presented. This suggests that bilateral activation of color processing areas in the brain is necessary in order to induce color afterimages. Whether these bilateral activations can be induced without hypnosis is a question for future research.

References

Sivkovich Fagin, O., & Mack, A. (2022). Negative Color Aftereffect in the Absence of a Colored Stimulus. Perception, 51(2), 77-90. Chicago.