Bias

Illusory Faces Tend to Be Perceived as Male

There's a strong gender bias in face perception.

Posted February 27, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- We tend to see illusory faces everywhere, a phenomenon known as pareidolia.

- When we detect an illusory face, we automatically perceive its social characteristics, like its expression, age, and gender.

- A new study reports that illusory faces are overwhelmingly perceived as male.

- This result provides new insights about how we encode and process faces.

Illusory faces are everywhere: from outlets and mailboxes, to peppers and clouds. The mere hint of two eyes and a mouth immediately triggers our face detection system to signal that there may be a face in our environment. There are even social media groups dedicated to finding and posting pictures of objects that look like faces.

Research on face pareidolia shows that when we perceive an illusory face in an everyday object, other facial properties come along for free. Rather than just seeing something as a face, we also attribute to it a particular expression, intention, age, and even gender.

The gender of illusory faces

In a new paper published this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Susan Wardle and her colleagues investigated whether illusory faces elicit gender perceptions and whether those might be biased one way or the other.

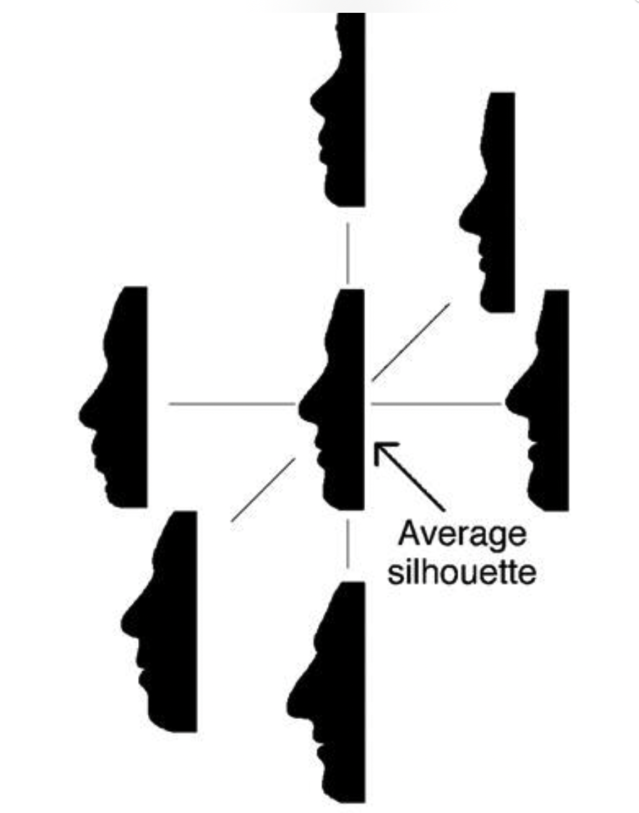

There are decades of research that point to a male bias when evaluating faces. In a study conducted in my own lab in 2007, we constructed an "average face silhouette" by morphing together a set of 24 male and 24 female face silhouettes. Even though the morph was composed of the same number of male and female faces, 72 percent of participants judged the morphed as being male. When asked to judge the gender of individual faces as male or female, 70 percent of judgments were male even though only 50 percent of faces were male. This is not just true of silhouettes; other face models have found a similar bias; when the gender of a face is ambiguous, ratings tend to be highly male-biased.

In the new study by Wardle and colleagues, rather than examining real or simplified human faces, the researchers selected a collection of 256 images of objects with illusory faces from various databases. Participants rated these images on a number of dimensions, including their face-likeness (how much they appeared like a face), their expression, age, and gender.

The results from the gender ratings were striking: participants judged the face-like objects to be male (81.4 percent) much more often than female (18.6 percent). Moreover, this effect was comparable across male and female observers.

Why is there such a large male bias for illusory faces?

Wardle and colleagues considered several potential explanations. First, they considered the possibility that the photographed objects themselves may have had implicit gender associations. To test this, in a subsequent experiment, the same objects (including potatoes, mailboxes, trees, and fruits), were modified to remove any face-like features. Gender ratings of these face-less objects suddenly showed no male bias at all. Another follow-up study asked participants to rate the named objects (e.g., "potato") as either female or male; again, no male bias was found.

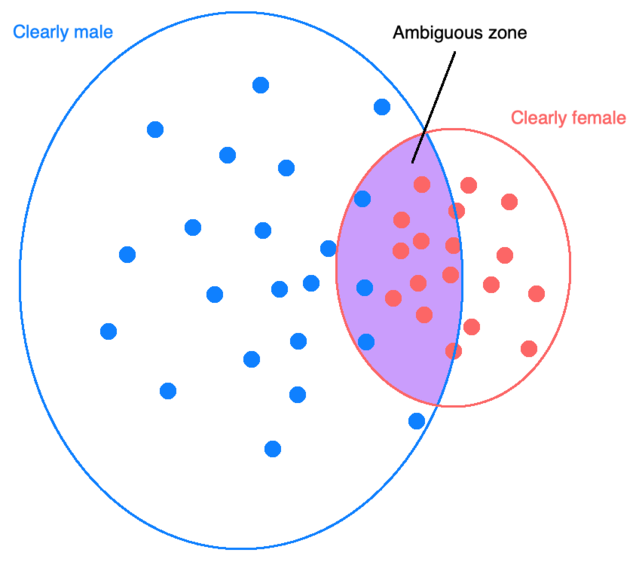

Another theory posits that a bias to rate ambiguous faces as male might stem from the greater physical variability that exists among male faces. Anthropological studies have found that male faces tend to be more physically heterogeneous than female faces (e.g. Alley & Hildebrandt, 1988). Greater physical variability can induce a bias in judgments because the proportion of ambiguous male faces and ambiguous female faces will not be equal. The Venn diagram below illustrates this:

Based on differences in variability, most male faces will appear to be clearly male, while a smaller proportion of female faces will appear to be clearly female. As a result, the region of ambiguity consists of mostly female faces. Even if ambiguous faces are 50 percent likely to be judged as male or female, this would still result in an overall male bias on the entire set of ratings.

A lack of characteristic female features?

Another possibility is that the choice of images that comprised the database may have been male-biased from the start, and participants' ratings simply reflect the bias in stimulus selection. However, this is unlikely. First, the researchers found that male and female observers produced the same male bias, so it is not likely that the gender of the researchers may have influenced the choice of stimuli in a systematic way. Second, the male bias did not show up when participants rated objects that were low on face-like features, nor when judging the gender of objects based on their names alone. That is, a potato without eyes looks no more female than male. Add the two eyes, and it suddenly appears male.

Could it be the lack of long hair? There are particular facial characteristics and accessories that mark faces as male or female. Perhaps in our society, there are more explicit indicators of female faces, such as long hair, or make-up. The lack of these accessories in the illusory faces may have been perceived implicitly as a signal that the faces were male.

Overall, the study by Wardle and colleagues adds to a growing set of evidence for male bias in judgments of faces. Future research may focus on understanding when and how this bias develops, and what it implies about the function of our face recognition system.

References

Wardle, S. G., Paranjape, S., Taubert, J., & Baker, C. I. (2022). Illusory faces are more likely to be perceived as male than female. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(5).

Davidenko, N. (2007). Silhouetted face profiles: A new methodology for face perception research. Journal of Vision, 7(4), 6-6.

Alley, T. R., & Hildebrandt, K. A. (1988). Determinants and consequences of facial aesthetics (pp. 101-140). TR Alley (Ed.), Social and applied aspects of perceiving faces.