Personality

Does Your Personality Determine How You Perceive Illusions?

How different individuals perceive ambiguous, bistable illusions.

Posted April 29, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- A new study investigates individual differences in the perception of ambiguous, bistable illusions.

- The Big-5 personality factors do not predict how quickly ambiguous, bistable images switch back and forth.

- However, participants who scored higher on a measure of "divergent thinking" experienced faster switch rates.

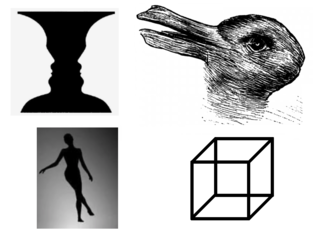

Psychologists have long been interested in how people interpret ambiguous, bistable images, such as the examples below.

Bistable images generally provide two equally likely interpretations, but observers tend to only perceive one interpretation at a time. For example, the spinning dancer (bottom-left image) can be interpreted as spinning clockwise or counterclockwise, but not both. Similarly, the Necker Cube (bottom-right image) can be interpreted as being viewed from the top (where the front face is on the left) or as being viewed from the bottom (where the front face is on the right), but observers can't hold both interpretations at the same time.

Instead, observers find that the interpretation switches back and forth between the two possibilities. Studies show that the rate at which the interpretation switches can be influenced by factors such as attention and eye movements. However, there are also large individual differences across observers: each observer tends to experience "perceptual switches" at a particular rate, which can be measured as the number of switches per minute while passively observing the image.

Individual differences of interpretation

Some observers experience very slow switch rates, with the interpretation switching only every 30 seconds or so. Other observers experience fast switching every two or three seconds. What drives these large individual differences remains a mystery.

In a new research study published by Annabel Blake and Stephen Palmisano in the journal Perception, researchers investigated potential sources of individual differences in the perception of both the spinning dancer and the Necker Cube, and asked whether these differences could be attributed to personality factors, including scores on the Big 5 Personality Traits as well as a measure of "divergent thinking".

For the Big 5, the researchers obtained scores on "openness to experience", "conscientiousness", "extraversion", "agreeableness", and "neuroticism". For measuring divergent thinking, the researchers conducted an Alternate Uses Task (AUT) that asks observers to come up with alternate uses of common objects, like a spoon or a brick. The AUT is thought to measure one aspect of creativity.

Results and limitations

Contrary to previous research by Antinori, Smillie, et al. (2017), none of the Big-5 personality factors predicted switch rates. However, performance on AUT did predict switch rates. Specifically, participants with higher scores on the AUT showed faster switch rates when observing the Necker Cube.

This result is a replication and extension of a 1984 study by Holger Klintman, which also found a relationship between "original thinking" and switch rates in the Necker Cube. However, Klintman's original study had participants fixate on a black dot at the center of the screen while they observed images. In Blake and Palmisano's study, participants were allowed to view the images freely in one condition, or fixate a small dot in another condition. The results were essentially the same regardless of the condition.

These results support the idea that creativity (at least the type of creativity measured by the AUT) is linked to "faster perceptual restructuring" (Blake and Palmisano, 2021). Importantly, this study did not measure a different type of creativity called convergent thinking (e.g. thinking of a unique solution that solves multiple constraints).

It is also important to note that Blake and Palmisano did not find the same results for the spinning dancer, which tended to have much slower switch rates overall than the Necker Cube. One possibility is that the silhouetted dancer is too difficult to switch, resulting in a floor effect.

Finally, although the correlation between divergent thinking and switch rates were significant, they were moderate to low: they found an R-value of 0.283, which means that AUT accounts for only about 8 percent of the variability in switch rates in the Necker Cube.

Still, these results at least suggest that cognitive creativity is related to perceptual flexibility. The ability to switch between two or more interpretations of an image may thus involve some of the same mental processes required to find creative solutions to a problem. Although this helps pin down one source of variability, there is still a lot (92 percent) of individual variability left to explain.

References

Blake, A., & Palmisano, S. (2021). Divergent Thinking Influences the Perception of Ambiguous Visual Illusions. Perception, 03010066211000192.

Antinori, A., Smillie, L. D., & Carter, O. L. (2017). Personality measures link slower binocular rivalry switch rates to higher levels of self-discipline. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 2008.

Klintman, H. (1984). Original thinking and ambiguous figure reversal rates. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 22(2), 129-131.