Memory

Instant Amnesia

How the brain quickly forgets irrelevant information.

Posted June 29, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Have you ever had the experience of checking the time, only to forget what time it is just a few seconds later?

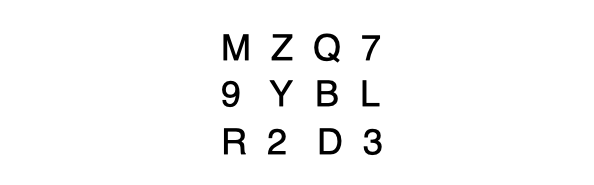

This experience of instant amnesia may be more common than we think. Psychologists have known for a while that much of the content of our visual experience quickly fades away when it is not the focus of our attention. George Sperling brilliantly demonstrated this in a classic study from 1960. Participants were briefly shown a grid like the following:

After 50 milliseconds, the grid disappeared, and participants were asked to jot down on a blank grid as many numbers or letters as they could remember. On average, participants correctly recalled about four of the letters in this "full report" condition or roughly 33 percent of the presented information.

However, by associating an auditory cue with each row of symbols, Sperling and colleagues devised a way to prompt partial reports. In this "partial report" condition, when the grid disappeared, participants heard either a high-pitch tone, a medium-pitch tone, or a low-pitch tone that cued the participant about whether they should report the contents of the top, middle, or bottom row, respectively. It's important to note that the tone always came after the grid disappeared, so it functioned as a retrospective cue for which row to report, rather than as a simultaneous cue for which row to look at or pay attention to.

This partial report condition revealed that participants actually held much more than 33 percent of the content in mind following the grid's disappearance. In fact, on average, participants could correctly report about three out of the four symbols from the cued row, regardless of which row was cued. This means that participants, at least for a brief moment following the grid's disappearance, held in memory as much as 75 percent of the grid's content.

Sperling's results showed two things: First, the content of our visual memory is initially very rich (as shown by the partial report results); second, unless that rich content is cued or attended to, it can fade out of memory in a split second (as shown by the full report results).

Attribute Amnesia

More recently, researchers at Pennsylvania State University pushed this second conclusion even further by suggesting that even when we do attend to a single item, we can still quickly forget much of its content if that content is not relevant to the task at hand.

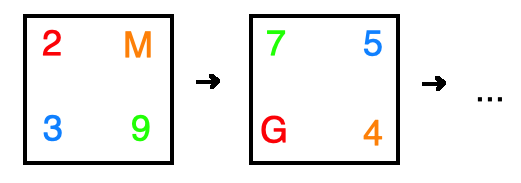

In their studies, Hui Chen and Brad Wyble (2015, 2016) presented participants with grids of letters and numbers, similar to those used by Sperling in the 1960s. However, the task was different: participants were asked to quickly identify the letter among three numbers and report its color. For example, in the grids below, the answer to the first grid should be "orange," and the answer to the second grid should be "red." Participants were quite accurate and quick at this task.

What participants didn't know was that on the 12th trial, after responding to the color of the letter, they would be asked a surprise follow-up question: "What letter did you just see?"

One might predict that this should be an easy question to answer. After all, the participant had just identified which of the four symbols was a letter (and not a number) and reported its color correctly. Yet, as their data show, only 35 percent of the participants were able to recall the letter correctly, even though they had just seen it a second earlier.

The researchers called this effect attribute amnesia, suggesting that it reflects a failure of memory consolidation. In other words, participants simply did not encode the memory of the letter into memory. Since their task was just to report the color, once they identified which symbol was a letter and extracted its color, the identity of the letter itself—no longer relevant for the task—was discarded and not consolidated into working memory.

These results are, in some ways, even more surprising than Sperling's original 1960 findings. It makes sense that when we are presented with a lot of information (e.g., a grid of 12 symbols), we can only hold so much of it in memory before it fades. But the results of Chen and Wyble showed that this type of instant memory loss could happen even if we are paying attention to the specific item in question. The key question is whether the attribute of the item (e.g., its identity as a letter, or the color it is printed with) is important for the task at hand. In Chen and Wyble's studies, the identity of the letter (beyond the fact that it was a letter) was not important for the task, and so this attribute was quickly forgotten.

What Time Was It?

In this light, it may not be so strange that we can quickly forget what time it is, even if we just checked the clock a few seconds ago. Suppose I'm planning to watch a TV show that starts at 8 p.m., and at around 7:42 p.m., I check the time to see if it's about to start. What I'm attending to when I check the time is whether the show is about to start. Once I decide that the show is not about to start yet, I might immediately forget exactly what time it actually is and just encode the fact that "the show is not starting yet." The attribute of exactly what time it is is irrelevant, and thus subject to attribute amnesia.

Facebook image: Africa Studio/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: wong yu liang/Shutterstock

References

Sperling, G. (1960). The information available in brief visual presentations. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 74(11), 1.

Chen, H., & Wyble, B. (2015). Amnesia for object attributes: Failure to report attended information that had just reached conscious awareness. Psychological science, 26(2), 203-210

Chen, H., & Wyble, B. (2016). Attribute amnesia reflects a lack of memory consolidation for attended information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 42(2), 225.