False Memories

Are We Living in the Past?

Research on multisensory processing suggests our sense of time lags behind.

Posted December 31, 2019

As the end of the year approaches, many of us are contemplating our past actions and making ambitious plans for our future selves. At the same time, we are reminded of the importance of being present and living in the now.

But what exactly is the present moment?

Although we may have an intuitive feeling that our sense of time is constant, it really seems to depend on which sensory modality (visual, auditory, etc.) we are using. The human brain takes between 100 and 300 milliseconds to process visual information, depending on the content of that information—a texture, a landscape, or a face all take different amounts of time to perceive. In contrast, auditory processing happens much quicker. For example, we can accurately determine the order of two beeps (which beep came first) even if they occur only 15 milliseconds apart. Likewise, we are able to gauge the direction a sound is coming from even when the time difference between the sound arriving at our two ears is less than 1 millisecond. Generally speaking, auditory processing happens much quicker and is much more sensitive to time than visual processing.

As humans, we are extremely visual creatures, with large portions of our brain dedicated to visual processing. Could it be that, visually speaking, we are living in the past? That is, if we are constantly processing visual information at a delay compared to auditory information, is our visual sense of the present happening a few hundred milliseconds later than our auditory sense of the present?

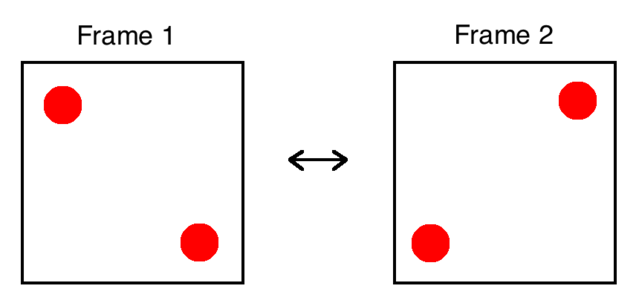

Researchers at Dartmouth College set out to answer this question by studying multisensory integration. In their study, participants were instructed to attentionally "control" an ambiguous motion stimulus—the apparent motion quartet (or AMQ). The AMQ consists of two dots on opposite corners of a square in Frame 1 which are replaced by two new dots on the other opposite corners in frame 2 (see the diagram below).

The AMQ results in an ambiguous motion percept which can be perceived as rotating clockwise or counterclockwise. It turns out that people can quickly learn to "mentally control" whether the dots appear to rotate clockwise or counterclockwise. (Try it for yourself here: AMQ video).

On each trial, Dr. Liwei Sun and colleagues instructed participants to mentally control the motion based on a brief auditory tone—a beep that was either low-pitch or high-pitch, corresponding to clockwise or counterclockwise rotations, respectively.

Importantly the researchers manipulated the timing of the tone relative to the frame change: sometimes the beep occurred 533 or 133 milliseconds (ms) before the frame change, but sometimes the beep occurred simultaneously with, or even 133 or 533 ms after the frame change.

What the researchers found was that participants were able to reliably control the perceived motion direction based on the auditory cue about 60 percent of the time, significantly above chance. Surprisingly, participants were able to exert control even when the beep occurred 133 ms after the frame change.

In other words, participants saw the frame change, then 133 ms later heard a beep that instructed them which way to interpret the motion that just occurred, and participants were still able to do this. In essence, participants were able to go back in time and influence how a past visual stimulus was perceived.

Can we alter the past with our mind?

Although we can never truly alter the past, we can quickly alter how we perceive and remember the recent past. And this does not require one to undergo hypnosis, implant false memories, or wait years and years for our memories to naturally fade. In fact, we can alter how we perceive an event that occurred a split second ago, simply by taking advantage of the fact that our auditory present is always happening a little bit ahead of our visual present.

So on this New Year's Eve, as you prepare to toast to a prosperous 2020, remember that at the moment you see the clock strike midnight, the new year may have already begun!

References

Sun, L., Frank, S. M., Hartstein, K. C., Hassan, W., & Peter, U. T. (2017). Back from the future: Volitional postdiction of perceived apparent motion direction. Vision research, 140, 133-139.