Education

Turn Your Kid Into a Reading and Writing Genius

One way to boost learning in a pandemic—no broadband required.

Posted January 29, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Dear Despairing Parents,

We understand why you’re on the verge of a breakdown over your son’s/daughter’s schooling. Most schools shut their doors nearly nine months ago. You’re juggling meetings or your own graduate courses on Zoom, often with your kids bursting into touch-and-go meetings with clients. If you’re like most of us, your broadband connection is decidedly iffy, and your kids occasionally have to attend class on your iPhone from inside the family bathroom. Moreover, the newspapers brim with warnings about just how far behind your kid now is from his or her grade level, courtesy of COVID—even if you’re fortunate enough to afford a pricey private school that’s continued to hold hybrid courses, partly online and partly in the classroom since at least September.

Now for a bit of good news. You can ensure your kid returns to school, reading up to four grade levels above your neighbor’s kid, the one who attends a cushy private school that meets in a classroom at least two days a week—even if you have a lousy Internet connection. The solution is surprisingly simple and also one that your kid wouldn’t get even in a traditional classroom. Insist on a regular diet of classic literature. Make your kid read classic literature.

Sure, the classics are full of everything educators now shudder at. Works written by mostly dead white men. White and usually affluent characters with problems like entailed estates and a sister who just put a serious dent in their desirability on the marriage market. (Yes, we’re looking at you, Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice).

Get your kid to trade at least 1-2 hours of reading literature or, even better, analytical articles from The Atlantic to The South China Post, which even some sixth-graders can read. Make reading a priority in your kid’s day. Be sure to read whatever your kid reads and put time on your calendar to discuss this reading with your kid. Ask and make clear you expect them to answer complex questions that nudge your kid toward connecting the world outside your windows with the details he or she has just read this morning.

You can expect two outcomes: your kid’s reading comprehension and writing will improve, whether you torment them with vocabulary words on flashcards or even discuss writing with them. As studies I’ve conducted over the past five years have revealed, everyone’s writing is like a fingerprint that reveals whatever you read habitually, in addition to your reading over the past year. Both news articles and Ye Olde Classic Literature also feature complex sentences and vocabulary words your kids will never encounter outside that instantly-forgettable list of vocabulary words on a spelling test.

At the beginning of the 2020 COVID outbreak, a colleague and I introduced a curriculum to primary and second school students under pandemic restrictions in China. Based on earlier studies, I already knew that powerful priming and language-style matching made mature students’ writing nearly mirror their regular sources of reading, in terms of the complexity of their word choice and sentence structure. We used the same strategy in teaching students in grades 4-9, many of whom were still grappling with English as a second language. Now, months, and dozens of students later, we can see our results. And they are remarkable.

Our average student’s reading comprehension and writing sophistication jumped more than four grade levels. Students who began our courses reading Diary of a Wimpy Kid read Pride and Prejudice in sixth grade. In another four months, they tackled Vanity Fair. We simply met with small groups of students on Zoom to discuss books and then focused on the short essays students wrote weekly, either in response to discussion questions or to their own chosen essay topics.

Primary and secondary education have historically treated reading the way dietary guidelines handle vegetables. Both are somehow good for you, yet no one can give you the fine-grained low-down on why your kids should swap broccoli for Pringles or trade Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (Lexile=940) for Vanity Fair (Lexile 1270). Currently, publishers and schools alike rely on Lexile scores to establish the difficulty of sources ranging from newspapers to required reading. Look up any source online, and you’ll likely spot a Lexile score ranking an article in, say, The Odyssey (1130) or To Kill a Mockingbird (870), based on (1) the lengths of sentences and (2) how commonly or rarely used its words are.

However, to accurately assess the difficulty of any form of writing, you need measures that also assess the complexity of sentences, since you can string together A Green Eggs and Ham-level of simple sentences with a succession of ands and arrive at a sentence that runs to over 1000 words. We’ve turned to Haiyang Ai’s software that analyzes word-choice and sentence structure for complexity and assessed students at baseline, then again at the conclusion of each term.

This student was a third-grader who lives in China and struggled to write a complete sentence in his early essays:

Essay #1

Do you know why do the boys what to painting the fence? Because Tom Sawyer is a good exponent, he can describe painting the fence to very attract and try to make hard to get this job, and say this work is good. He will say: “you can go swimming every day but you can’t painting the fence every day, just like my brother Sid wants to do it, but he was not good at painting, so Sid can’t to do it.” Tom use "the less you get the more you want features" to let the boys to work for him, and get a lot of amusing thing. So this is why the boys want to paint the fence. I think that Tom will be a good boss in the future.

However, in his later essays, his writing changed dramatically, due almost entirely to reading Tom Sawyer, as well as Honey Bees: Letters from the Hive. In class, he and other students also talked about the novel and his writing informally over Zoom. At the end of the eight-week term, he turned in this final essay.

Essay #2

Scientists have discovered that a bee colony is democratic. The queen bee doesn’t decide where bees want to fly and where to gather honey. Bees dance in groups, express their ideas through dance, and more and more bees join the dance, which means that this is the idea of most bees, and all bees must follow.

I think maybe it is the queen substance unites the bee colony. It makes every bee calm. What makes me surprised is that when the old queen bee doesn’t produce queen substance, there will be bees in the colony that can produce queen substance, and there may be more than one. They need to fight, and the final winner becomes the queen bee, then the bee colony with the queen substance begins to be peaceful again.

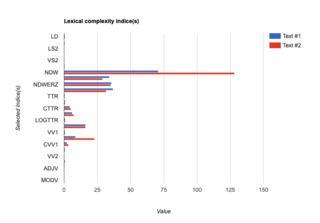

This student’s assessment for his writing’s word-choice or lexical complexity looks like this, with his first essay (#1) represented by the blue lines in the bar chart to the left, and his final essay (#2) by red lines.

Note that this student’s number of difficult (rarely used) words (NDW) nearly doubled in just two months, taken from writing samples of equal length.

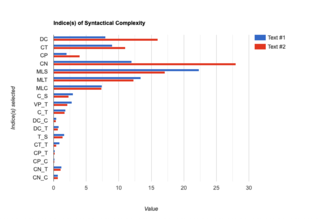

Moreover, this student’s level of gains is still more marked in how he constructs his sentences—in a course with only minimal instruction in writing, which can be seen in the second chart below.

In samples from both his first and final essays, his use of dependent clauses (DC) more than doubled, while his use of complex nominals (CN) increased by about 2.5 times. In contrast, his median sentence length (MLS) shortened dramatically solely due to the student recognizing run-on and fused sentences and using appropriate punctuation to separate one sentence from another.

The take-away? Even if you have spotty broadband, ensure your kid reads challenging material. Be sure you read alongside your kid to ensure he or she has a strong grasp of the books’ or articles’ meaning across the sentences and paragraphs. Even if you never utter a peep about writing, let alone punctuation, your kid will emerge from the pandemic with stronger reading and writing skills than he or she would from that tony private school you might never afford.